Utilizing the “big room”—collocating all project team members onsite in a single environment—to achieve true integrated project delivery (IPD) can be the best way to drive efficiency, reduce waste, and improve project outcomes through a shared pain/shared gain contract structure for all stakeholders. But it also can create a lot of noise in the form of information overload. Only by managing information as a Lean commodity can the IPD team realize the full potential of the process.

“Our goal was to discover, reveal, and measure information flows so that we could improve collaboration,” says Reid Senescu, a Stanford University researcher looking into the flow of digital information in the big room environment. “In this case, we are essentially treating information like Lean manufacturing would treat a part in an assembly line. We want just-in-time delivery of information that speeds through the project team as quickly as possible.”

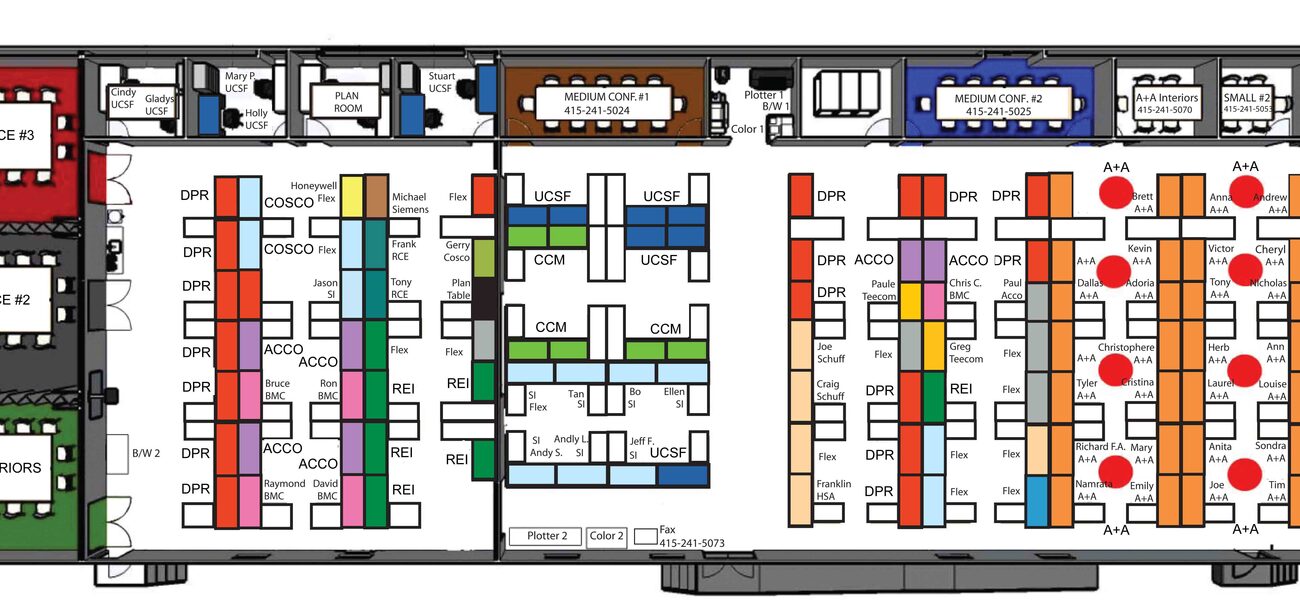

One of the largest big rooms ever assembled combines stakeholders for the $1.5 billion UCSF Medical Center at Mission Bay in San Francisco into one collocated organization called the Integrated Center for Design and Construction (ICDC). Begun in 2009 with about 80 people in the ICDC, the 12,000-sf command center now houses more than 300 architects, engineers, contractors, and subcontractors rotating through while the project is under construction. Collectively, they generate an enormous amount of information, but only a small fraction of it is critical to the mission of each individual. The key is to cut through the noise and funnel the right information to the right people at the right time.

Lean Information Flow

Senescu and his team of researchers used a large-scale Northern California hospital project as a case study in Lean information flow.

“Lean is about creating value,” says Senescu. “But the question is: Who are you creating value for? The answer is that the stakeholders decide the value—not necessarily the current customer, but the future stakeholders. If the project is a hospital, you’re creating value for the patients, doctors, nurses, and so on.”

Senescu leveraged this research to start CloudLeaps. CloudLeaps software maps the way documents are exchanged between team members using their existing tools (e.g. ProjectWise, Window Servers, Box, SharePoint etc.) and current processes. It tracks how and when files get viewed, edited, and exchanged, then automatically applies algorithms to these behaviors to map the relationships between dependent documents, eliminating the need for process mapping.

“If you are working on the structural cost estimate, and somebody changes a dependent file like the structural analysis spreadsheet, instead of hundreds of email updates sent out to the entire team every time something on the project is changed, you get a customized notification that information specifically relevant to you has changed,” says Senescu.

CloudLeaps features a shared project dashboard to keep the project team informed on information activity that is relevant to them. This added level of workflow transparency also helps identify critical roles, such as who is at the center of information exchange at any given time.

“We graphed who most of the information flowed through on a month-to-month basis to determine who was at the center of the exchange,” says Senescu. “For example, early in the design phase we found a lot of the information was flowing through the general contractor.”

The app can also identify potential bottlenecks and communication gaps based on who has viewed which documents.

“If a subcontractor is about to start installing something in the next couple of weeks, but they are behind in reading information created by all the other disciplines, this gives you a red flag,” says Senescu. “When you have this kind of information up front, you can respond proactively.”

The Up Side of the Big Room

The big room approach—which is supported by technologies like SmartBoards, high-speed internet, and online document sharing—is part of the IPD model. Properly managing the flow of information can make for a much more successful big room.

“The big room is a collaboration space where a multi-disciplinary team consisting of the owner, architects, general contractors, designers, and subcontractors work together to accelerate decision-making, improve communication, and avoid project delays through all stages of design, preconstruction, and construction,” says Atul Khanzode, director of construction technologies at DPR Construction, general contractor on the project.

“IPD is based on a relational contracting model that is different from a traditional design-bid-build method of delivery,” says Khanzode. “It usually involves a best-value selection process for team participants who operate under a negotiated contract with mutual pain share/gain share where the team succeeds together rather than as individual players.”

“With the ICDC (at UCSF), the designers, general contractor, subcontractors, and owner representatives all started collocation at the schematic design phase,” says Khanzode.

To better understand the pros and cons of big room dynamics, researchers from Stanford and Finland’s Aalto University analyzed information flows and other metrics, and interviewed more than 80 ICDC team members.

One of the most significant benefits they found was a dramatic reduction in latency—the amount of time between when a request for information (RFI) is filed and when it is resolved.

In fact, the ICDC team has achieved an almost 99 percent success rate under an incentive program designed to drive rapid turnaround of all RFIs and to get RFIs answered without needing resubmission.

“Average turnaround time for RFIs at the Mission Bay project is around three to four days,” says Khanzode. “Since everyone is together, the team can address things quickly, document it, and move on to the next issue.”

Another advantage to the big room is an increased level of transparency that gives individual team members a deeper understanding of everyone else’s work. This heightened level of situational awareness reduces waste and helps everyone adapt more rapidly to changes.

“If something is going to change on the architectural side, you don’t want the subs to start modeling it for their MEP,” says Khanzode. “In a big room it’s easy to communicate these things so the subs can do something else in the meantime and still be very productive.”

Big Room Downsides

Not surprisingly, the biggest challenge cited in the large open environment is distraction. This has been especially true for team members who had completed significant work before joining a big room—such as the fire protection subcontractors, structural designers, and medical equipment personnel.

“A lot of people like to work in a more traditional type of office,” says Khanzode. “They feel like anybody can come up and interrupt their work in an open environment.”

Another drawback cited was time wasted in too many inefficient meetings.

“In some situations, a subcontractor or structural designer would get called upon to answer a five-minute question, but they still had to sit through the whole six hours,” says Khanzode. “So teams wanted to find more efficient ways of incorporating those individuals without wasting their time. One approach was to have them participate only for the period of time they needed to be there and structuring discussion on those topics so that they can be present or dial in at the right moment.”

Lessons Learned

According to Khanzode, the key to a successful big room is designating a dedicated facilitator who can focus the group at critical points and help resolve any conflicts as they arise.

“This person can be a designer or somebody on the contractor side who is good at facilitation,” says Khanzode. “The typical trend is that there is a sense of euphoria when you first get in a big room and people are really excited, but you have to be able to maintain that or it fades. Keeping this momentum going requires someone who is respected and talks to all the team members regularly.”

Structuring schedules to allow for both meeting time and working time is also important. Now meetings are scheduled every other week to give everyone involved more time to prepare.

Multidisciplinary teams can maximize small breakout sessions by quickly using modeling tools to produce detailed concepts for group consideration.

“When you have the designers, architect, and BIM staff all together, why not just have them produce something very quickly that they can show to the rest of the team to give everyone an immediate understanding of what is being considered?” says Khanzode. “We’ve seen a lot of benefit in doing this because of the amount of group clarity it provides in decision making.”

Other best practices include matching room layout with organizational structure.

“When we started in UCSF Medical Center’s ICDC, for example, everyone sat together with their own companies,” says Khanzode. “To speed up the flow, the team arranged the room into clusters that matched the organizational layout of the project. So the hospital group sits together, the outpatient building group sits together, the energy center group sits together and so on. This streamlined the process quite a bit.”

It is also important to improve processes and assess team progress on a regular basis.

“To get the most out of a big room, you need to revisit these things as a group, maybe once a month or more, and really look at what is working and what isn’t; then adjust accordingly,” says Khanzode.

By Johnathon Allen

This report is based on a presentation by Khanzode and Senescu at the Tradeline 2013 Lean Facility Lifecycle Conference.