Motivating organizational leadership to address the growing limitations of aging science facilities can be a challenge for facility managers. Strategic assessment models like facility condition, revitalization rate, and asset age are powerful tools for stewarding facilities, but in advocating for renewal, which models are most likely to drive action? Officials at NASA considered four of the most common models before settling on the use of a simple “readiness” metric for measuring operational risk and developing a reasonable business case for new facility investment.

“Our clients—the people who occupy the spaces or control the funding—are not necessarily going to understand the way facilities people speak,” says Kim Toufectis, NASA’s master planning program manager. “So an intuitive model for conveying what’s important and what it should cost is essential.”

Toufectis proposes five key criteria to find a suitable model: It has to be credible, portfolio-wide, budget-linked, intuitive, and compelling enough to prompt action.

“Whatever model you use has to be plausible within our profession,” he says. “It also has to look across the entire portfolio. I don’t know how many times I’ve been in discussions with leaders where I took a narrow problem to them and they said, ‘Great, you’ve convinced us it needs to be solved. Take it out of the budget everywhere else.’ So we need a way of talking about the problem that looks across the entire portfolio. It also needs to be easy to understand. And, of course, linked to budgets. If it’s not linked to budgets, you’re merely having an academic conversation.”

Facility Condition

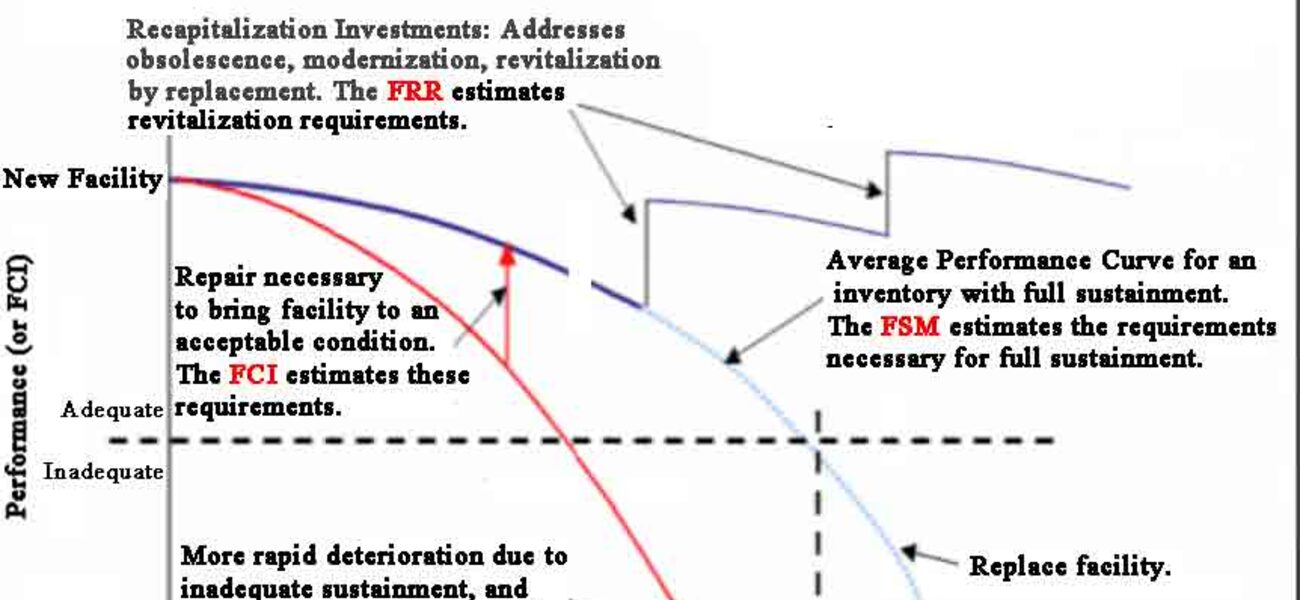

The facilities condition model is a widely respected, complex model designed to help administrators make choices about the condition and upgrade needs of each individual building in their inventory.

“The logic of the facilities condition model is pretty straightforward,” says Toufectis. “Facilities deteriorate. If you catch them in time, you can bring them back and extend their useful lifespan.”

While it’s a credible and well-established industry model, it’s not portfolio-wide, as it tends to look at only one asset at a time. This makes it difficult to apply the model across a portfolio of hundreds or thousands of assets, or to link it to an overall budget.

“And it’s a complicated model, so it’s not very intuitive,” says Toufectis. “If you haven’t seen it before, the chances are not very good that you’ll absorb it in the briefing where it is defending a case for funding.”

Revitalization Rate

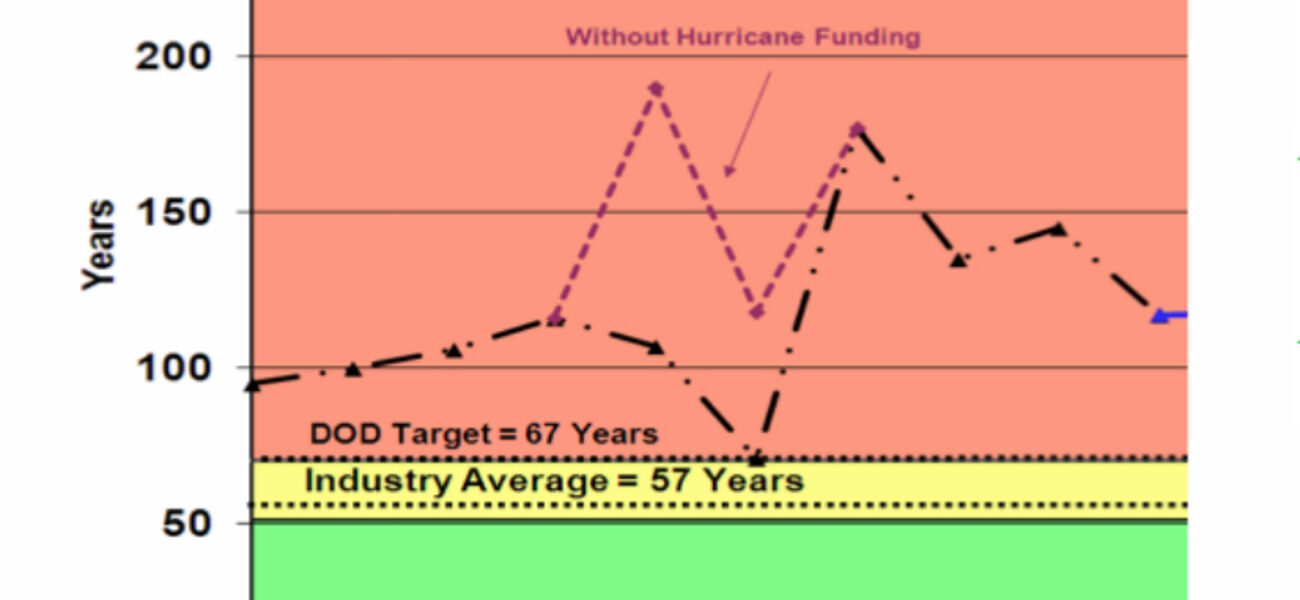

Facility revitalization rate models track the total investment levels applied to a facilities portfolio, dividing the total amount of funding by how much value it’s protecting. This accounts for the amount of repair and upgrade required to offset obsolescence, aging materials, and new technology requirements.

“Once again, this model gets used a lot,” says Toufectis. “So, yes, it’s credible. More importantly, it’s also portfolio-wide and budget-length. But, again, it’s not very intuitive.”

For a year, NASA managed to get this model down to what they considered a “yellow level” of risk, meaning that there was just enough money to revitalize facilities at the needed rate.

“We were at the edge of what we considered a red level of risk,” says Toufectis. “In fact, the only reason we got to yellow was because a hurricane smacked our coasts. So extra money let us repair damage, but didn’t actually make our facilities much readier in the aggregate.”

Asset Age

It’s generally accepted that, without significant reinvestment, facilities wear out over time, so average asset age trending is a widespread model.

According to Toufectis, the real, useable life span of a modern laboratory is about 40 years.

“I would submit that the 40-year mark is the point where we have sucked the useable life out of a lab building,” says Toufectis. “The next churn that we do in that building is likely to leave our clients—the scientific researchers—unhappy with the place we’ve created for them. Now, it may happen earlier in some areas and later in others, but I have tested this with other facilities managers, and 40 years has proven to be a pretty good starting point for that discussion.”

While the model is credible and portfolio-wide, it isn’t budget-linked or intuitive.

“It seems intuitive, but if you build one new facility, how does that help the facilities that you didn’t invest or reinvest in?” asks Toufectis. “It turns out to not be as intuitive as I expected, and reversing the aging trend of a substantial facilities portfolio costs a great deal, which means it’s not likely to prompt action, either.”

Readiness

Ultimately, NASA settled on the use of a readiness metric to develop a facilities renewal model that tracks the percentage of a portfolio at or beyond the age of obsolescence to enable the organization’s future mission success.

“To use a model like this,” says Toufectis. “You need a desired end-state—somewhere you want to go. In our case, we defined that as being ‘readier’ by lowering the risk that declining facilities would interfere with NASA’s work.”

Of course, NASA’s specialized, high-technology work demands a lot from its facilities, and those demands tend to increase as technology advances.

To keep pace with these demands NASA seeks to shrink its footprint as it renews or replaces outdated assets.

“If we incorporate the right technology in the replacement, we can replace older facilities with something smaller; we feel that we could get 20 percent smaller if we were to renew the whole portfolio set,” says Toufectis.

One of the keys to this approach is focusing on facility robustness and flexibility.

“It means designing buildings that can put up with a lot of change, for instance not packing an HVAC system into a mechanical room where it can’t be expanded,” says Toufectis. “This becomes important when you need to maintain a capability while the technology it depends on changes over time. We try to find configurations that will make us, if not future-proof, at least future-resilient.”

When NASA first adopted this model, most of its facilities were already in their 40s.

“They were at a yellow level of risk,” says Toufectis. “Not the end of the world, but not a good fit with future needs. Imagine, as we move into the future, relying on research facilities in their 60s, 70s, and 80s without ever having renewed them. That is a scary picture for me. And it got leadership attention at NASA.”

One of the modeling possibilities considered was to renew about half of the portfolio while consolidating by 20 percent.

“Under that model, we would get close to two-thirds of our portfolio under age 40 at any given time,” says Toufectis.

While each of these models helps facilities stewards frame difficult choices, the key to using them successfully in a business case is knowing what key stakeholders understand and want. Another critical factor is knowing what your specific organization needs out of a model before trying to evaluate the best candidates.

“Perhaps most importantly, you need to define an end state that is far enough away and as powerful as your strategic plan is,” says Toufectis. “NASA has a strategic plan that changes every five years. If I start development of a facility now, and that facility doesn’t open until after the five year strategic plan is finished, I’m going to have to establish a longer view about where we want to take our facilities to support that work.”

By Johnathon Allen