The Affordable Care Act (ACA) is changing medical delivery and funding streams, with an impact on business models, institutional and facility planning, capital projects, asset utilization, and strategic positioning for healthcare facilities. Meeting the challenge of delivering high-quality, low-cost healthcare will require determining the fee-for-value proposition behind these changes—how the cost of changing healthcare services affects quality outcomes, and ways to measure these outcomes, says Anthony Roesch, director of healthcare consulting for HOK in New York. Healthcare organizations will increasingly look to mergers and acquisitions, as well as new partnerships, to limit costs and prolong the life of aging facilities, as the ACA forces them to shift from a fee-for-service financing model to a quality-of-care, outcomes-based model. Rather than all treatment being delivered at the hub, or hospital setting, the new model leverages services available in the community to cover an entire region or state.

“The healthcare industry has been trying to move forward, to change culture, change structure, and change facilities in advance of these new regulations,” says Roesch, who specializes in strategic operational and capital planning for healthcare organizations.

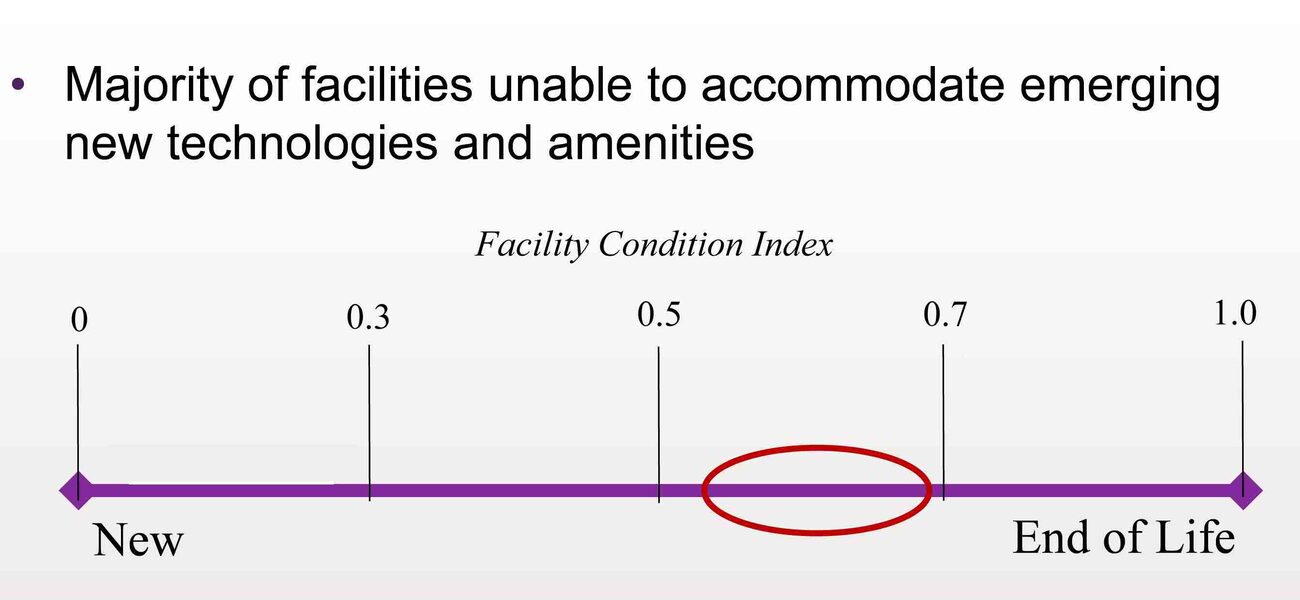

“We are nearing the end of life for many facilities, which will have a profound effect on how we allocate dollars in the future. We will move from building hospitals and research infrastructure to building more integrated facilities,” he says. “Given that it can take a good five to 10 years to develop new healthcare facilities, we are at a crucial juncture in decision-making.”

These buildings, whether new or repurposed, must perform at a very high level for both mechanical systems and patient-related technology, to operate at a substantially reduced cost.

Healthcare reform was necessitated in large part by an over-capacity and under-utilization of hospital resources, says Roesch. Demand for hospital space, for example, has dropped by as much as 40 percent in the last 10 years. Healthcare is shifting from vertically focused tertiary health centers—some specializing in trauma and academic medicine and serving a fairly defined patient base—toward broader centers, integrating across a market.

“Healthcare reform focuses on reducing unnecessary hospital admissions,” he says. “We move volume to physicians and focus on treating patients more in short-stay or observations beds, not inpatient acute-care beds, with the focus on getting patients out of the hospital.”

The predicted results will be:

- A drop in hospitalization rate from 112 to about 90 per 1,000 patients;

- A 10 to 15 percent decrease in hospital admissions, with more short stays and observation;

- A 30 to 50 percent increase in ambulatory or outpatient care;

- A 20 to 40 percent decrease in the need for hospital space, as admissions drop;

- A 16 to 30 percent increase in demand for hospital-based provider visits;

- More high-cost chronic diseases managed in interdisciplinary clinics or practice units;

- Hospital consolidations through construction or mergers and acquisitions to achieve 20 to 30 percent cost reductions;

- Consolidating large acute care facilities in favor of small regional acute care hubs and specialty care anchor facilities;

- Creating more regional ambulatory care, community primary care, and urgent care facilities.

Moving Along the Care Continuum

Central to healthcare reform is the idea of healthcare as a continuum that follows patients as they move through the system. The new directive is “Triple Aim”: obtaining the best healthcare value by looking at population health outcomes, patient satisfaction, and cost of care.

“Healthcare is currently fragmented,” says Roesch. “There is little communication between your primary care physician, therapist, rehabilitation specialist, and hospital acute care providers. With healthcare reform, information must be communicated across the healthcare spectrum, so the information in your record travels with you.”

Mandating that records be ubiquitous across the system increases efficiencies by allowing coordinated, rather than episodic, care.

As hospitals become responsible for upstream, preventative healthcare, as well as downstream care, they must keep meticulous medical records and coordinate treatment plans with other venues, since patient care and payment will no longer be based strictly on days in a hospital bed. For instance, under the new system, a patient undergoing knee surgery may spend one night in the hospital at a billed cost of $15,000, then transition to outpatient care at a community rehabilitation facility at considerably lower cost.

The shift from traditional fee-for-service in healthcare toward fee-for-value, largely driven by the Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement structure, relies on performance-based metrics to determine how well the new system is working. Hospitals must demonstrate they can reduce operating costs by a minimum of 15 to 20 percent, and show that more resources are going toward primary and preventative care, in order to contract for insurance company payments.

“An insurance company will say, ‘We’ll pay a lower rate for the cost of heart surgery, but a more favorable one for the cost of primary care toward preventing heart disease,” says Roesch. “We are already starting to see a shift in the revenue stream from what was once predominantly inpatient cases, to outpatient revenue. That not only has a profound effect on an institution’s bottom line, but it initiates a change in the mindset of physicians and clinicians.”

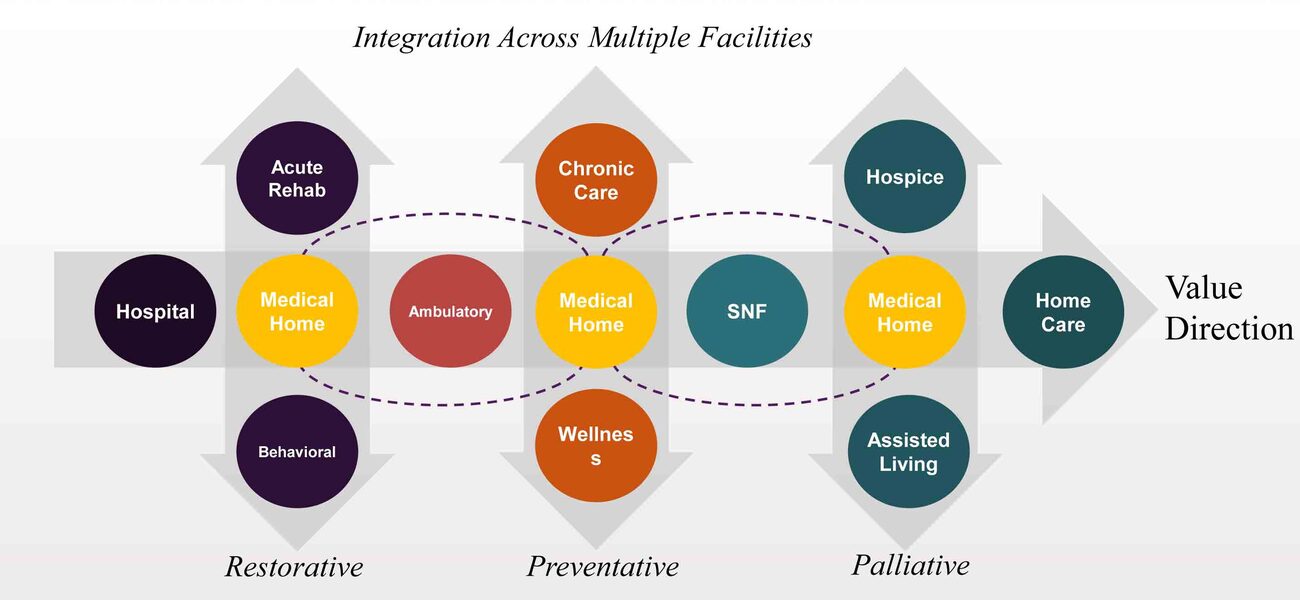

Analyzing data on length of recovery, infection rates, number of tests administered, cost of care, and rehabilitation treatment plans shows whether fee-for-value incentives are working, and whether population health is benefiting from the changes. “What we are going to see in the future is a bundled payment structure, that is not paid per hospital discharge, but paid per patient,” says Roesch. This integration of healthcare across multiple facilities will cover the range of care, including restorative care, such as acute rehab and behavioral health; preventative and wellness care; and palliative care, such as hospice and assisted living.

Facilities Impact

Very few inpatient hospitals are currently equipped with the emerging technologies and amenities needed to accommodate the transition toward outpatient treatment.

“It’s unlikely that facilities built in the 1950s or '60s can perform at levels required to meet the new standards,” says Roesch. “Most of our current facilities are built on the wrong platform of care.”

While most institutions are currently in a holding pattern on capital projects, the next few years will bring expenditures for rebuilding infrastructure, acquiring community space to improve the healthcare continuum, and repurposing existing facilities. Hospital directors and planning committees will be looking at partnerships with other healthcare systems, as well as mergers and acquisitions, to pool resources and serve patients in the proper setting.

Repurposing will help accommodate greater outpatient flow, as the need rises for more local outpatient facilities rather than large downtown hubs, and physicians move from hospitals to be closer to populations they serve.

Baby boomers, who tend to use the healthcare system at a rate three to four times the average population, will affect these trends, but not in the way once predicted. “The standard line in construction has been to build capacity in expectation of this generation, however we are seeing a shift away from hospital beds toward ambulatory care, so the impact will not be what we expected 10 years ago,” says Roesch. Rather than expanding hospital space, the new model will support research to study the diseases of an aging population; regional ambulatory care centers and urgent care centers to deliver care at a reasonable cost; and continued growth in community primary care programs, home care, assisted living and hospice programs. “In essence, healthcare reform is about how we are going to meet the demand. We can’t keep the same cost structure and the same delivery system and be successful,” says Roesch.

By Mary Beth Rohde

This report is based on a presentation at the Tradeline Facility Strategies for Academic Medicine and Allied Health 2014 conference.