Organizations of all types are using location-based social media data and other user-generated information to improve workspace design and functionality. By researching occupancy data, user satisfaction ratings, and other metrics, facility designers are finding smarter ways to lower costs and create efficiencies. While some organizations mine existing trace data automatically generated by mobile devices and building management systems, others are developing customized platforms dedicated to capturing key information. Some go so far as to integrate those platforms directly into the facilities themselves to create “sentient buildings” that interact with their occupants in real time, all with the intent of using data to shift the focus from managing buildings to enabling user communities.

Whether it’s by adapting existing consumer-oriented software or developing dedicated custom apps for workspace interaction, facility designers now have access to an unprecedented amount of detailed information regarding user satisfaction and space functionality.

[A description of some of the available off-the-shelf software appears at the end of this report.]

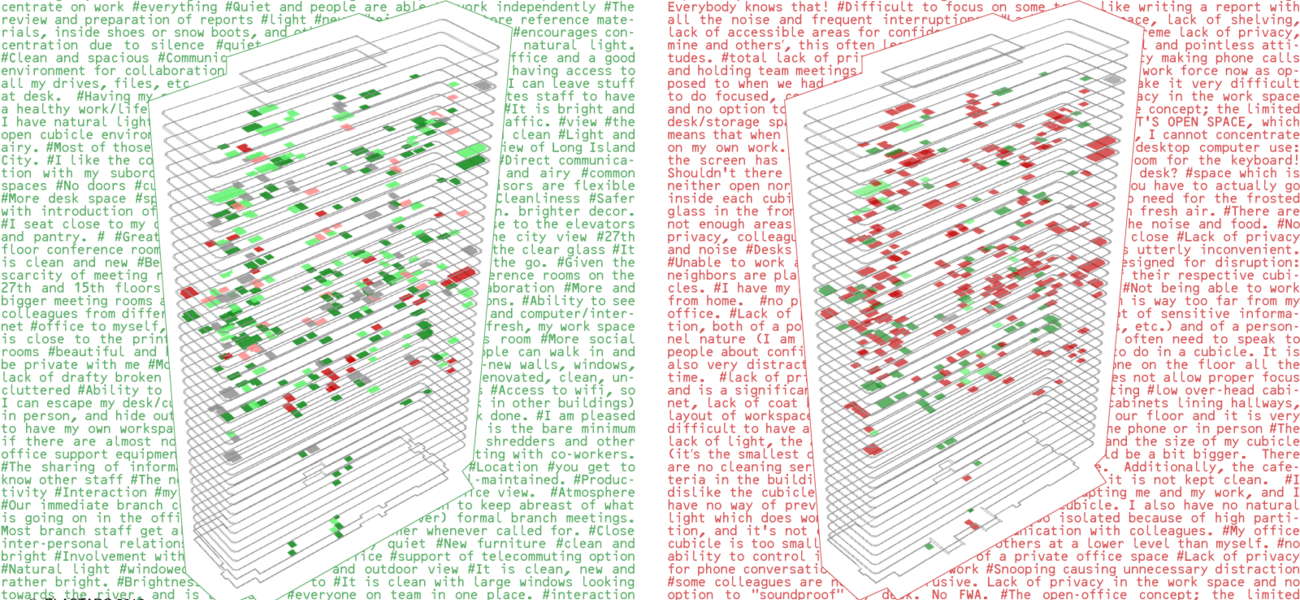

“A lot of this is just a matter of thinking differently about how we collect and use social information,” says Melissa Marsh, founder of PLASTARC, a design and consulting firm that specializes in applying social data and research to optimize workspaces. “It’s not about using social media for business promotion or communication. It’s about using the data generated by lots of people walking around with mobile devices sharing their thoughts on everything from their food preferences to their spatial preferences and seeing how we can learn from that as designers, planners, and building operators.”

A diverse range of techniques can be employed for gathering occupant feedback, from scraping and analyzing existing data, to conducting voluntary user surveys, to creating dedicated mobile apps that connect users to space reservation and building systems in real time.

Some companies, like Mozilla®, choose a direct, hands-on, do-it-yourself approach to gathering user experience information; others repurpose existing technologies, like Foursquare® and Twitter, for supporting internal planning initiatives with opt-in participation. Arizona State University’s new Beus Center for Law and Society, home of the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, is pushing new boundaries by investing in development of dedicated technologies that combine digital and physical interaction in real time.

“We are now at a point where everyone has a platform for testifying about their experience,” says Marsh. “And there are a lot of options available for people to do things like check into a space, as well as rate their experience in that space, whether it’s a building, a conference room, or a phone booth. So it’s really a matter of looking at how you can capture that information to make better planning decisions.”

Leveraging Dedicated Platforms – WeWork

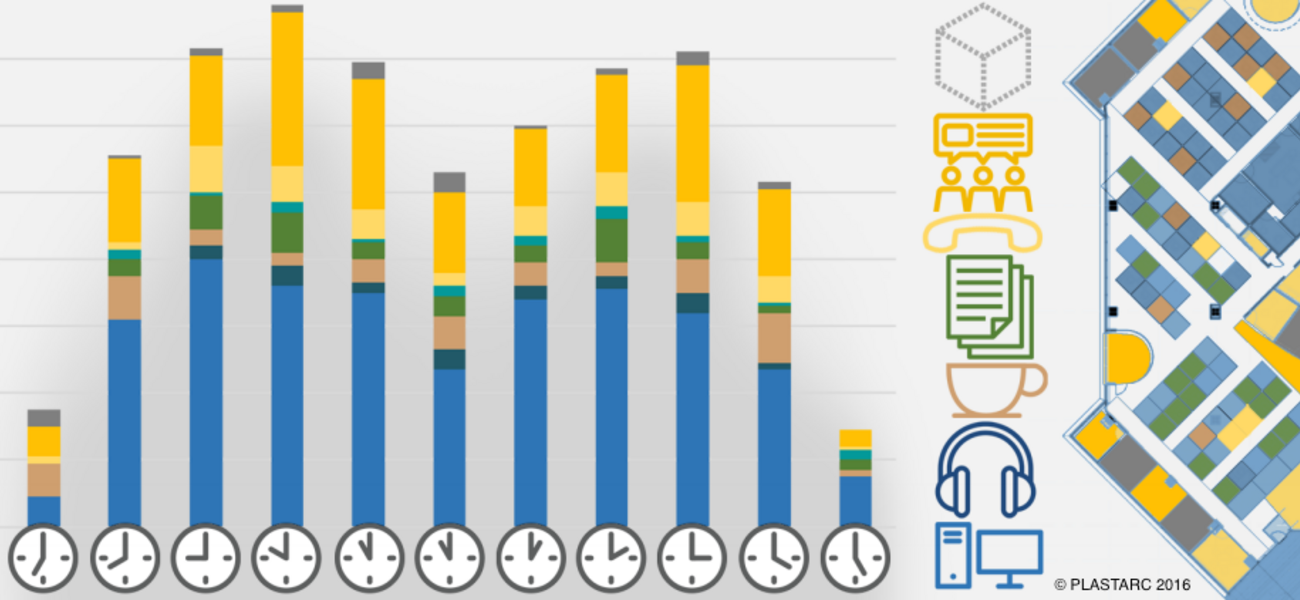

One organization maximizing this approach is New York-based WeWork, which provides shared workspace to professionals in major cities globally. Since all WeWork members must use a dedicated app for reserving workstations, conference rooms, and other spaces, the organization has access to a tremendous amount of user data that can be leveraged to optimize space planning.

“Our product research team mines the member platform for data relating to space use, satisfaction, occupational needs, and common complaints,” says Carlo Bailey a design researcher at WeWork. “Then we use that data to reverse-engineer spaces and make them better.”

WeWork analyzes a wide range of metrics, including how long spaces are booked for, when they are booked, and the length of lead time. If a user gives a room a poor post-meeting rating, the app will ask why and use algorithms to determine whether it’s due to AV issues, design, lighting, or other factors. This information is then aggregated across the entire real estate portfolio to identify trends and anomalies.

“We developed the app to close the loop rapidly and get that data back to our design team as fast possible. This allows us to see and respond to what each individual market, occupation, and building needs,” says Bailey.

The data has revealed an increasingly common trend toward smaller meeting rooms. Where many WeWork buildings started out with meeting rooms designed for eight to 12 people, the reality is that most meetings consist of groups of four or fewer, so floorplans were adjusted to offer more meeting spaces of smaller sizes.

“We also analyze existing social media data in every market we serve, because we really want to understand the demographics of shared workspaces for each of our locations,” says Annie Cosgrove, a design researcher at WeWork. “We collectively feed so much information into the social digital sphere that we now have the opportunity to track trends in behaviors and sentiments across populations, demographics, and industries. We’re constantly working to connect these external data sources to our internal analysis of the communities we create, in order to tailor the member experience for each local community.”

Open-Source Engagement – Mozilla

Reflecting its unique open-source culture, Mozilla uses a direct feedback model for gathering occupant input on space performance. Using a “fail fast” approach, Mozilla tests new space ideas by implementing them in the real world, rapidly getting direct feedback from users, and then adjusting spaces based on need. As part of this approach, the organization reserves 20 percent of its construction budget for post-occupancy construction and mediation.

“We’re essentially crowdsourcing information from the people working in our offices to come up with better designs and create an environment that helps them to be happy and productive,” says Rob Middleton, director of worldwide workplace resources at Mozilla.

While approximately 40 percent of Mozilla employees telecommute, the organization establishes physical office space in locations when a critical mass of workers is achieved. In these cases, Mozilla typically signs shorter five- to seven-year leases to stay flexible.

“We apply best practices for creating new work environments and then ask our people to provide feedback on their experiences in them. We host weekly team calls, create Google Docs™ for capturing comments, and conduct online surveys, so people can make their opinion known in whatever way is most relevant and safe for them. It’s a very collaborative approach,” says Middleton.

Mozilla recently engaged this process moving into a new London office with highly successful results. By switching from assigned desks to a voluntary hot desking system, the organization cut their space requirements in half for the same number of people, and reduced real estate expenses by 30 percent.

Contrary to the way many companies operate, Mozilla invites staff to participate in the real estate selection process, using surveys to collect their opinion on everything from bike rooms, to coffee stations, to window views. The results of that survey then become the starting point for the real estate search. Survey results are also made public to the group to provide transparency in the decision-making process and increase buy-in.

“People were skeptical of the flexible seating approach at first but, because we engaged them in the process, they ultimately agreed unanimously. It does take more time to do it this way, but the benefit is that, when everyone is on board, there’s a lot less friction, and it creates a more productive environment,” says Middleton.

Like WeWork, Mozilla discovered a need for smaller meeting spaces, and more of them. The new London floorplan features high-vaulted open space with smaller six-person work pods separated by an array of public spaces, meeting rooms, and video conference booths.

“After the first 30 days in the new space, we did a Google Docs™ request for feedback, and the only negative input we received was that we needed to install dimmer switches on the lights. People were otherwise very satisfied and felt that the space better supported how they actually work,” says Middleton.

Interactive Buildings – ASU’s Beus Center for Law and Society

Pushing the concept even further, Ennead Architects recently partnered with Unified Field to complete a pilot “sentient building” at Arizona State University: the new Beus Center for Law and Society.

“ASU really wanted their new home for the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law to be something beyond architecture, to impact not just the physical landscape of downtown Phoenix but ASU’s academic culture and legal pedagogy,” says Tomas Rossant, partner at Ennead Architects. “We worked with Unified Field to co-develop a digital app in conjunction with the building that gives each person a customizable digital interface between themselves and the law school, so the building talks to them and they talk to the building.”

The custom-built app serves as a rich mobile interface for connecting users to the building and its community. When the app is on, and a user walks into the building, a floor-to-ceiling monitor senses and greets them. From there, app users can do things like find fellow students and professors in their social network, or learn where open lectures are taking place and get turn-by-turn directions. As it gets used moving forward, the app will generate valuable data for helping the building evolve in response to how the community actually uses it.

The custom platform developed for ASU is modular so it can grow and expand along with the building and campus. Meanwhile, even more ambitious projects, such as the new development at New York’s Hudson Yards, aim to take the concept of interactive buildings and spaces to the neighborhood and community levels.

“We’re entering the era of sentient buildings, where facilities in sectors like higher education and healthcare can—and probably should—have a smart-phone user interface,” says Rossant. “Imagine the implications for hospitals if you could eliminate waiting rooms. Where—as soon as you arrive—you are greeted by a nurse and taken directly to a procedure room that is already prepped for you.”

“We now have this transparency of resources that has never existed before, where we have the opportunity to collect data from what people are doing in real time—whether they’re booking a room, adjusting the temperature, or interacting with a colleague through their devices,” says Marsh. “And with the proliferation of social media, we now have to improve the actual performance of the spaces that we provide, rather than just whitewashing or marketing their spatial experience.”

By Johnathon Allen

Off-The-Shelf Social Tools for Better Design

Many existing technologies can be easily adapted or mined for quantification of user experience and design initiatives. Here are a few that can be leveraged for better space planning.

Foursquare® is a location rating app for all space types with which participants can check into locations, specify their ‘likes,’ share recommendations, and rate the space. In a corporate environment, it can be used to rate a particular conference room or a space within a facility. Foursquare application programming interfaces grant developers access to the company’s database of locations, as well as venue check-in information. https://developer.foursquare.com

Comfy integrates with any digital building management system and turns personal mobile devices into an individual thermostat for each occupant. The app allows users to check and adjust the temperature settings in the room they are in, or will be in. In a shared environment, the app aggregates thermostat request data to adjust temperatures for the community. In addition to providing valuable user feedback on comfort levels, it also helps companies reduce energy costs by throttling down systems when occupancy levels are lower. https://comfyapp.com

DropThought is a kiosk-based feedback platform that allows users—from students and staff to employees and visitors—to review and rate their experience of a space and provide feedback. For example, organizations can use DropThought in a pantry space to allow people to report what offerings they like or don’t like, or what items are out and need to be restocked. Instead of having people go through a facilities management ticketing system, they can connect directly to the service provider while generating valuable data on user preference. http://www.dropthought.com

Twitter: Is a popular micro-blogging platform that organizations are increasingly using to share and refine information regarding workplace experience. Organizing data with hashtags allows users to sort and share information relevant to a specific space or initiative. Twitter’s “REST” API allows developers to access core Twitter data, including: timeline updates, status data, and user information, while the “Search” API gives developers the ability to tap into Twitter search and trends data. https://dev.twitter.com/rest/public

FitBit®: And other fitness trackers are worn devices that provide an interactive platform for tracking personal activity, fitness, and daily wellbeing. The Fitbit Web API enables third-party applications to access and write data on behalf of users that could potentially be collated with building and workplace data to reveal trends relating to occupant experiences. https://dev.fitbit.com