The Children’s Research Institute (CRI), the research arm of Children’s National Medical Center in Washington, D.C., has seen its research programs expand, bringing the need to accommodate more staff and projects. A new innovation campus is in the works, but the move to the former Walter Reed Army Medical Center Campus will take four years to complete. The institute is therefore focusing on laboratory densification, both in the current space and the new campus.

CRI currently contains 130,000 sf of research space in the main hospital building for about 500 faculty and staff members. “We have very limited lab support space, and offices are scattered throughout the space. Over the years, most of the support space was converted to core facilities and freezer farms, so the environment is really difficult to manage,” says Kerstin Hildebrandt, vice president of research administration for Children's Research Institute.

Combine and Collaborate

In 2015, as part of its facility master planning, the institute engaged faculty in a conversation aimed at challenging norms around space and facility management. Instead of allocating space to individual researchers and their teams, they brought together stakeholders to find interdependencies that would lend themselves to colocation.

Using Lean methodology, CRI’s bioengineers followed workers during their day and observed distances between key work spaces and resources used by various team members. “We involved people from the front line—technicians, postdocs, junior faculty,” Hildebrandt says. In some cases, they were able to buy new equipment to serve multiple colocated teams.

Besides responding to a space crunch, CRI was reacting to changes in the way science is done. “We now see interdisciplinary research groups that are collaborating locally, nationally, and internationally in a team science environment,” Hildebrandt says. “Big data and the related requirement for high-performance computing are becoming essential, and the ability to support mobility across all of your facilities, when you have an aging building, is really a challenge.”

Instead of allocating space based on funding, they revised plans for the existing space as if every full-time equivalent had funding. Each research center established a multi-disciplinary space committee to review and address the unique program requirements and challenges. As a result, only full professors were given individual offices; lab staff had their desk space reduced from 5 linear feet to 4, and each lab-based FTE was assigned 8 linear feet of bench space. Most importantly, the committees took the data from their planning conversations to colocate projects and people whose work fit well together or who would benefit from collaboration.

densification.png

“This process hasn’t been easy, but it has been supported by our research community, because it has engaged everybody, is data-driven, and is transparent,” Hildebrandt says. Another factor in building staff acceptance of the changes was the buy-in from top management of the institution. “We had leadership support all along, especially financially to purchase sit-to-stand desks and to buy shared equipment. Our senior investigators no longer associated their standing in the organization with assigned square feet.”

The densification project made room for 10 to 20 percent more work spaces. The related data gathering and analysis were important for planning the next phase, but also for managing current situations, such as the annual influx of summer interns. “We know who’s working on what bench or on what part of the bench, and we have little buffer spaces where we can squeeze in temp workers,” she says.

Hildebrandt says she’s noticed positive effects from the project. “Of the people who are colocating, we have seen an increase in joint trainees and collaborations on grants and publications. Those who are still working in isolation are becoming the outsiders.”

A New Home, with New Challenges

The Walter Reed Army Medical Center was closed in 2011, and the location freed up for other uses two years later. (The Walter Reed name continues at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, now located in Bethesda, Md.) Children’s National Medical Center obtained the right to develop a 12-acre section of the campus and plans to relocate its research efforts to the former Armed Forces Institute of Pathology building, four miles from the hospital campus.

Creating the new space comes with many challenges. The largest part of the building, built in the 1950s Cold War period, was designed without windows, because it was supposed to withstand a hydrogen bomb dropped on the White House. Because federal buildings do not have to meet current building codes, the facility required a preliminary renovation so that Children’s could obtain a certificate of occupancy. In addition, the campus is a designated historic district, so the new inhabitants’ plans are subject to historic preservation oversight.

To manage the pace of change and the requirements of all the stakeholders, it was important to have a vision, says Irene Thompson, the project director overseeing the creation of the new Children’s National Research and Innovation Campus. The vision is this: “Children’s National at Walter Reed will transform the future of pediatric medicine through innovation and research that advances the health and wellbeing of children.”

“At times, stakeholder management has been challenging because of competing priorities, but returning to that mission and vision has enabled the team to move forward effectively,” says Thompson.

It might have been easier just to take over the entire 330,675 sf of lab space for CRI activity. Instead, the institute has chosen to allocate space to industry and academic partnerships, with the goal of encouraging collaboration and shared knowledge. JLABS@Washington, Johnson & Johnson’s DC incubator/accelerator, will occupy 24,500 sf, which will bring to the location as many as 50 startup companies at a time that are focused on child health innovation. (The academic partner has not yet been announced.)

“One of the attractions for JLabs is the fact that we will be pursuing novel, high-impact opportunities in pediatric genomic and precision medicine, anchored by our Center for Genetic Medicine Research, our Rare Disease Institute, and the Clinical Molecular Diagnostic Laboratory, says Hildebrandt. “We are hoping that when a startup company applies for space in the building, there will be preference given to those who can collaborate and align with those fields,” says Thompson. JLabs will design their incubator floor, in addition to shared collaboration, events, and amenity space on another floor.

That leaves the institute some room to work with, but by no means an oversupply. In their current cramped space, they have about 118 sf per FTE. Architects at Elkus Manfredi provided a benchmark of 227 sf per FTE, but that would not have fit in the available space. Thompson and Hildebrandt, with their stakeholders and outside consultants, sought to be economical with space while creating productive places for research.

Embracing Current Research Patterns

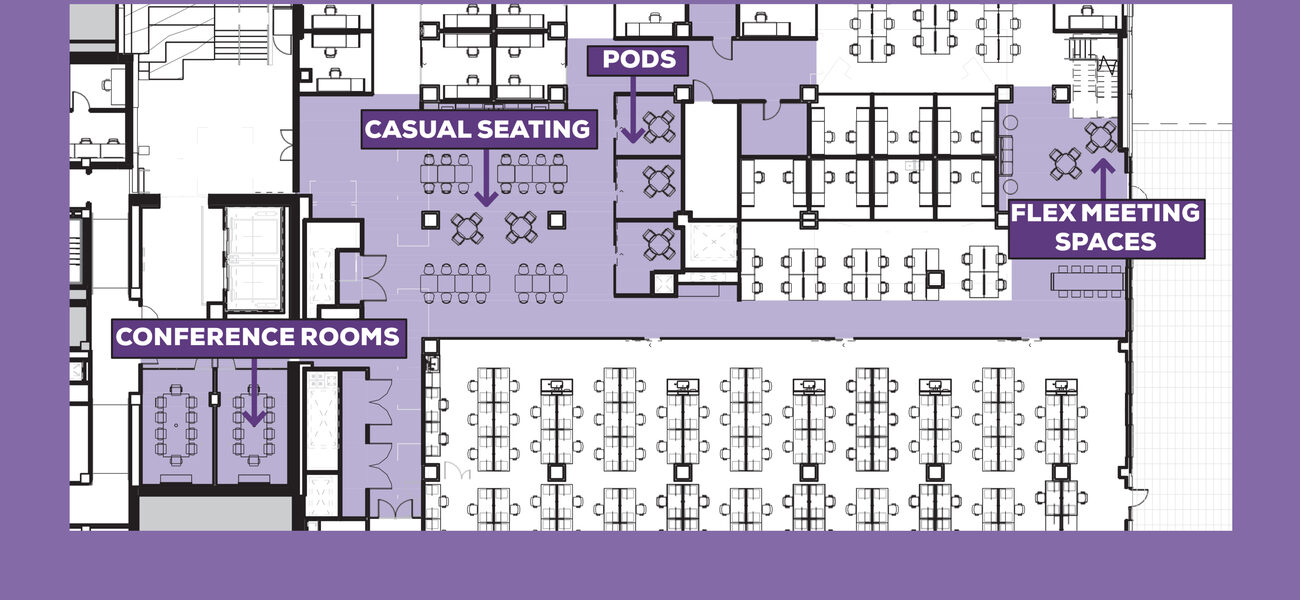

The institute has reworked its design several times in response to new information and stakeholder input. The current plan, with move-in scheduled for 2020, gives investigator teams 211 sf per FTE—not quite the benchmark, but close. How did they get there?

- Adjusting the planned 8 feet of bench space per FTE down to 6, and increasing support spaces and dedicated workstations to reflect the fact that researchers today are spending more time at their desks and less at the bench. The ratio of bench-to-lab support space was increased to 50:50.

- Setting the default office size to 120 sf, so employees can double up.

- Wherever possible, using flexible furnishings and shared desks. “Practically nothing is fixed to the wall or floor except for the pillars and the sinks,” says Thompson. “We don’t build anything permanent except for the stuff that connects to water pipes and exhaust pipes. You have no idea what the performance of science is going to look like in 20, 30, 50 years.”

- Establishing conference and huddle spaces for groups of varying sizes.

- Setting aside space for trainees, interns, and visiting scientists.

The first phase of the project will open in 2020 to coincide with the hospital’s 150th anniversary. Future phases of the Walter Reed project include finishing the renovation of the former pathology institute building to introduce windows and skylights.

One part of the institute’s strategic plan is to recruit the next generation of researchers, so the Research Institute’s leadership paid special attention to feedback from junior faculty and staff. “Young people look at space very differently. They care much less about office sizes—they want state of the art technology as well as social buildings that have plenty of collaboration space that fosters interaction, team-based research, and Friday night innovation events.” says Thompson.

By Pat Washburn

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

Elkus Manfredi Architects

|

Architect

|