An aggressive workplace transformation to an open floorplate with no private offices, implemented across 1 million-plus sf in three locations, allowed Unum Group to consolidate about 40 percent of its worldwide real estate portfolio, turning the vacated space into $53 million in sub-leasing revenue over the next 10 years. Despite the consolidation, the refurbished office buildings are equipped with a raft of appealing amenities, from coffee bars, micromarkets, and cafeterias to fitness centers, quiet rooms, and gaming areas.

Sending employees home was not the intent of the $100 million initiative, but the project is serving Unum well in the pandemic-driven shift to remote work.

“We built our model to be as flexible as possible, and the limited good news from the past 18 months is that we have leveraged that flexibility to no end, with no disruptions to the business,” says Paul Larkins, assistant vice president, Real Estate Strategy and Projects for Unum.

The nation’s largest disability insurer, Unum is the product of a series of mergers and acquisitions that took place in the late 1990s. The company has a workforce of more than 10,000 employees spread out over 3 million sf in 40 cities and three countries.

Despite establishing an employee-per-seat ratio of 4-to-3, Unum did not set out to densify when it started planning the massive overhaul of campuses in Chattanooga, Tenn.; Portland, Maine; and Columbia, S.C., where the employee populations were roughly 3,000, 2,800, and 800, respectively. Rather, the transformation is the result of an initiative that began in 2015 to find savings and promote a more uniform corporate culture across the multiple sites and position them for the future.

Up until then, Unum’s traditional workplace layout was typically 15 percent office and 85 percent open—“floors and floors of 65-inch-tall, 7-by-7-foot cubicles,” says Larkins. But instead of adopting the latest iteration of workstations, the CEO issued a new challenge: “He said, ‘I don’t want you to keep coming to me every five or six years with the next evolution of a space standard. Tell me what you think we should build for the business, regardless of culture and challenges.’”

That tall order triggered a sweeping transformation, one that took a completely fresh look at the company’s workplace strategy, capital investments, and deferred maintenance, culminating in the rebuilding of each floor of the targeted facilities from scratch.

Defining Objectives

To understand the drivers, scope, and language of such an undertaking, Larkins’ team engaged in a discovery process that included visioning sessions and a workplace performance index (WPI) employee survey in conjunction with Gensler, the project architect. Focus groups with diverse segments of the workforce—administrative staff, call center managers, new and veteran employees—asked about office space preferences and features that made them more productive. The team also toured half a dozen other large corporate campuses to see what their peers were developing. In the lead-up to a statement of the project outcome, employee engagement and retention emerged as a high priority. With its legacy computer systems and average workforce age of 46, Unum was especially concerned with recruitment.

“What makes a 22-year-old millennial want to come to an insurance company in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and basically get excited to code applications in languages that they had no education in, like Fortran?” asks Larkins.

The need to attract, retain, and engage talent was accompanied by two additional “pillars of success”: flexibility and adaptability, and a central focus on the customer, which in Unum’s case is its employees.

The overall enterprise solution had five desired outcomes:

- Use the new work environment to encourage innovation, growth, and smart risk;

- Implement a mobility strategy to improve space efficiency and adaptability;

- Equip employees with seamless technology to work wherever best supports their productivity;

- Unify sites with consistent Unum personality and standards while celebrating local flavor;

- Use leadership by example to motivate and communicate change to employees.

Equity Across the Workplace

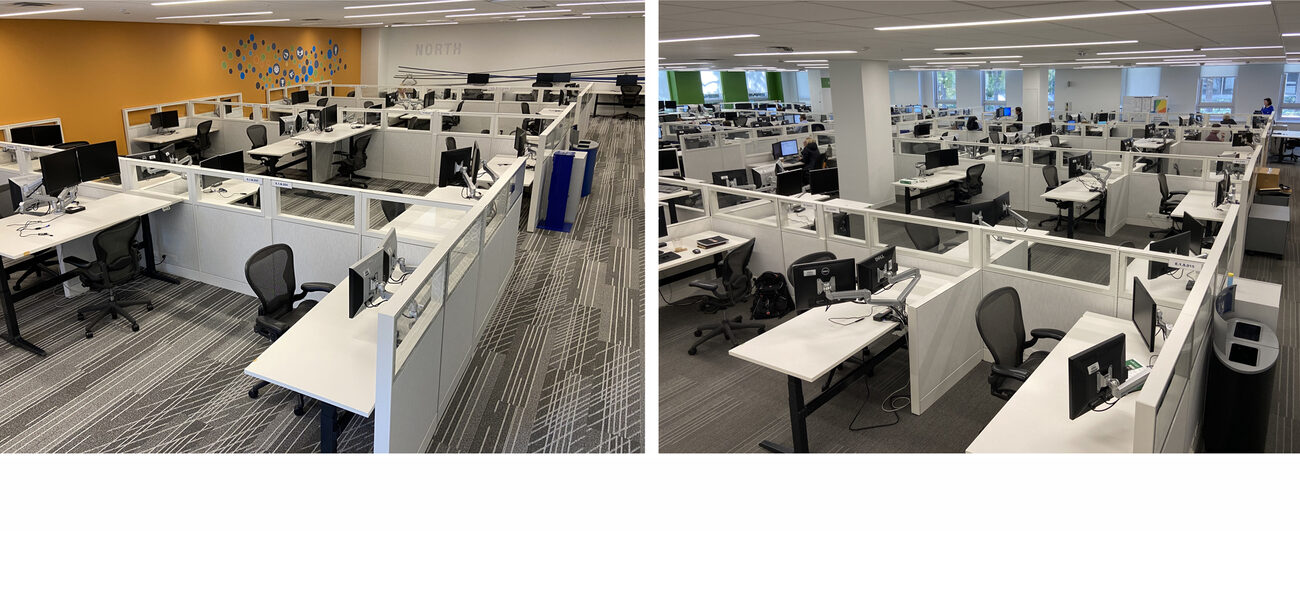

A small pilot project for a technology group in 2016 highlighted the benefits of collaborative, agile space. This led to a decision that broke drastically with tradition: doing away with private offices to adopt a completely open plan, with universal work seats regardless of corporate rank. The one-size-fits-all workstations are clustered in neighborhoods of between 45 and 60 seats, supplemented by several other types of space: for casual collaboration, different sizes of meetings, and centralized areas for drinking water, supplies, and eating. Perimeters are left open for access to views and daylight for all.

“Everything is the same,” says Larkins. “All departments are painted with the same brush. There is no difference according to managerial level or hierarchy. Equity permeates the organization.”

The 6-by-6-foot, 52-inch-high workstations have only two components: an electronic sit/stand desk equipped with dual or triple monitors on arms, and a wheeled credenza or pedestal that an employee can easily roll to another location, simply by pushing—no lifting, and thus no ergonomic challenges. Those employees who did not come into the office every day were assigned a locker instead of a credenza.

The new scheme has three levels of meeting rooms. Focus rooms, one for every 20 employees, measure 64 sf and accommodate two to three people. Huddle rooms, one per 30, are 96 sf and hold four to six. Conference rooms, one per 40, are 180 sf and fit eight to 14 attendees. The total of 613 meeting rooms represents a 36 percent increase in quantity and diversity from existing environments.

Despite concerns that there wouldn’t be enough seats for everyone who wanted one (a perception that Larkins admits gave him “headaches”), badging data revealed that on average only 65 percent of employees came into the office every day, supporting the four-person to three-seat ratio.

“For us, it was a huge leap to get to something so innovative,” says Larkins. “The components of the workstation cannot be changed. If people don’t like sitting there, they can move to a collaborative space or go home and work.” But, he emphasizes, “this project was not driven to send people home. The goal was to provide flexibility for all, so they can sit anywhere that best supports how the business needs to be done.”

Change Management

Supported by users’ and stakeholders’ positive reactions to the 2016 pilot project, the new plan received executive approval in July 2017. Construction took place in the three cities, each with a different contractor, in 23 phases over the following 30 months, with completion scheduled for January 2020.

A concerted change management plan was developed to communicate and promote the transformation to employees. Sponsors provided leadership by example while clearly and repeatedly articulating the need for the new workplace design.

An ambassador program played a key part in the plan, serving as a bi-directional communication channel between the project team and employees. Unum deliberately avoided assigning this role to senior management, selecting instead individuals from the workforce at large—“line managers, administrative folks, just regular employees,” says Larkins—to demonstrate enthusiasm and support for the new space concept. Ambassadors also reinforced the “what’s in it for me” benefits to their co-workers and were tasked to monitor progress after move-in to ensure the desired behaviors continued. The project team specifically sought out any areas of business resistance, for example those departments that were heavily paper- or phone-intensive, or had specialized equipment or storage needs.

“We were mindful to speak to their feedback in a positive way, to show them how their needs would be addressed in this flexible model. That allowed us to make solutions before it was time to move.”

The team also utilized a bevy of other communication vehicles—emails, websites, video, FAQs, newsletters, town halls—to mitigate resistance, accelerate adoption, and maximize the impact for the business.

All these efforts proved effective: In a post-occupancy survey, 86 percent of respondents reported having had enough information and time regarding the change process.

Measurements and Learnings

That same post-occupancy survey revealed additional favorable ratings: 81 percent approve of the look and feel of the new design, with 67 percent agreeing it represents the brand; 78 percent say that conference rooms are right-sized; and 72 percent endorse the support of mobile work. Ratings for the way the integrated technology, connectivity, and collaboration technology work are also close to 70 percent.

Some concerns that surfaced may have more to do with adjusting to the new environment than things that genuinely need correction. For instance, 70 percent of respondents cited noise as an issue in the new space. With the new partitions more than a foot lower than the old ones, Larkins wonders whether that reaction stems from perceived noise or actual noise.

Almost 80 percent of respondents felt they were interrupted more frequently in the flexible desk setting. Larkins proposes a simple remedy: Employees who need to do heads-down work are encouraged to move out of their department neighborhood to a quieter, less visible area when they need to concentrate.

Concern about getting a seat was voiced by 46 percent of survey respondents. Many said they felt compelled to arrive early in order to find a vacant desk. That’s a natural response to the four-to-three person-to-seat ratio, explains Larkins, pointing out the availability of other seating options in the neighborhood to which their work group is assigned.

There was also some pushback over confidentiality in the glass-walled meeting rooms when certain data was displayed on the large wall-mounted monitor, thus visible to passers-by. The solution Larkins recommends is to avoid posting truly sensitive information, like that related to employee performance, on the big screen, instead sharing it on participant laptops.

A sticking point that remains is the meeting room reservation tool, which applies only to conference rooms and is not very easy to use. It is primarily a problem of technology integration and administration, one that Unum continues to investigate. The smaller rooms are available on demand, to avoid being booked but not utilized. Every meeting room is equipped with sensors that record usage and feed data to an app that helps planners analyze utilization and decide if changes are in order. Employees can call up the app on their phones to see what rooms are available, without having to scour the floor in search of one that is unoccupied.

How satisfied is the workforce with the new space? Overall, 82 percent agree that it is more flexible and that the aesthetics reflect the Unum brand. At 64.5, the post-occupancy KPI score is four percent higher than before the renovations, and Larkins expects it to rise further as more employees are surveyed.

Pandemic Consequences

Construction was completed on schedule, at the end of February 2020. A few weeks later Unum sent 99 percent of its workforce home in response to the pandemic. Offices re-opened in May 2020, but at a much lower-than-expected level of occupancy. Repopulation initiatives and plans have been interrupted, and 15 months later, roughly 450 employees have yet to experience the new space.

In the meantime, several other changes have been implemented, most a result of the migration to remote work. All desk phones have been eliminated, replaced by Internet-based soft phones. Mail delivery, previously four times a day, is now entirely electronic—a long-term goal that was finally propelled to fruition. Cleaning had already shifted to daytime instead of night, and now is more frequent.

When employees did return, they did so in reduced numbers. Instead of directing them to a few consolidated areas, most Unum sites decided it was best for them to go back to their pre-pandemic neighborhoods, even if it meant scattered occupancy—and thus more maintenance—throughout the building. (The U.K. office was an exception, keeping everyone on one floor.)

“Otherwise, we would have had strangers from completely unrelated departments sitting together with no benefit for collaboration,” says Larkins. “We didn’t want to introduce another layer of disruption.”

Printers and other equipment specific to a department remained in place for the same reason. “Our return strategy might have been different if planners had known how long the pandemic was going to keep people at home,” he notes.

Looking to the future, Larkins predicts that the seat-per-person ratio will change, either naturally, by more staff choosing to work remotely; or by hiring employees based on remote talent pools in other locations. Leadership has learned and accepts a culture that embraces an in-office and work-from-home solution going forward.

“As a strategist, I have to be prepared and forecast the impact of the ratio changing, but I can’t answer by how much until we see a definitive return-to-office mentality, which may be 12 to 18 months away.”

He foresees the development of scenarios with tiers of hypothetical outcomes. “What does a 30 percent or a 50 percent reduction in office participation look like? If that becomes a reality, how do we re-align our capital plan to work in that direction?”

It might mean monetizing more real estate, or redefining surplus space for the business’s need to drive new reasons and outcome for office use.

“We might keep the same amount of space, but have employees come back to a different experience, with more amenity, team, or meeting space,” says Larkins. “We can’t make exact predictions right now, but at least we can be prepared with a variety of scenarios.

“The new normal can be frustrating,” he continues, “but we count our blessings that we were able to get the transformation done before everything else turned everyone’s world upside down.”

By Nicole Zaro Stahl

By the Numbers

- Affected square feet: 1,052,000

- Enablement: 7,300 swing moves

- Employee capacity: 7,003

- Work seats: 6,280

- Capital Expense: $92,441,800

- Operating Expense: $7,558,200

- Spend categories

- Soft (PM/ARCH/ENG): 7.8%

- Construction: 58.7%

- Technology: 4.7%

- Furniture: 16.4%

- Moving/Relocation: 2.3%

- Miscellaneous/Other: 10.2%