The phrase “lab of the future” typically refers to a flexible, open floorplan designed to promote collaboration and cross-pollination between researchers. But these buzzwords have been used for decades, with open labs dating back to the mid-’60s and flexible casework to the mid-’80s. So how successful have these features been, and what defines the lab of the future in 2015 and beyond? According to the researchers who use them, open labs do promote collaboration, but they also can cause frustration and friction among different personalities and research needs; and closed labs, contrary to popular thought, do not seem to inhibit collaboration or the use of shared resources. But for all this talk about collaboration, dedicated collaboration spaces are the lowest priority among researchers.

JacobsWyper Architects of Philadelphia examined the results of multiple R&D facility redesigns across the country—surveying the people involved to determine what was working, what wasn’t, and what they want from their future lab spaces.

“In the middle of the 20th century—65 years ago now—we were seeing research facilities designed in ways that align with today’s description of the lab of the future,” says Terry Jacobs, a founding partner at JacobsWyper. “In addition to open floorplans, mobile casework and overhead services represent some of the largest changes in lab design over the past 80 years. So is that it? Has the open design been so successful that it doesn’t need to evolve?”

“If we’re designing space for researchers, then why not research the researchers?” says Jamie Doran, a senior associate at JacobsWyper Architects. “So we sent out a survey to several clients and industry colleagues to find out what lab users and facility managers really think of their existing spaces and what they want to see in their ideal future facilities.”

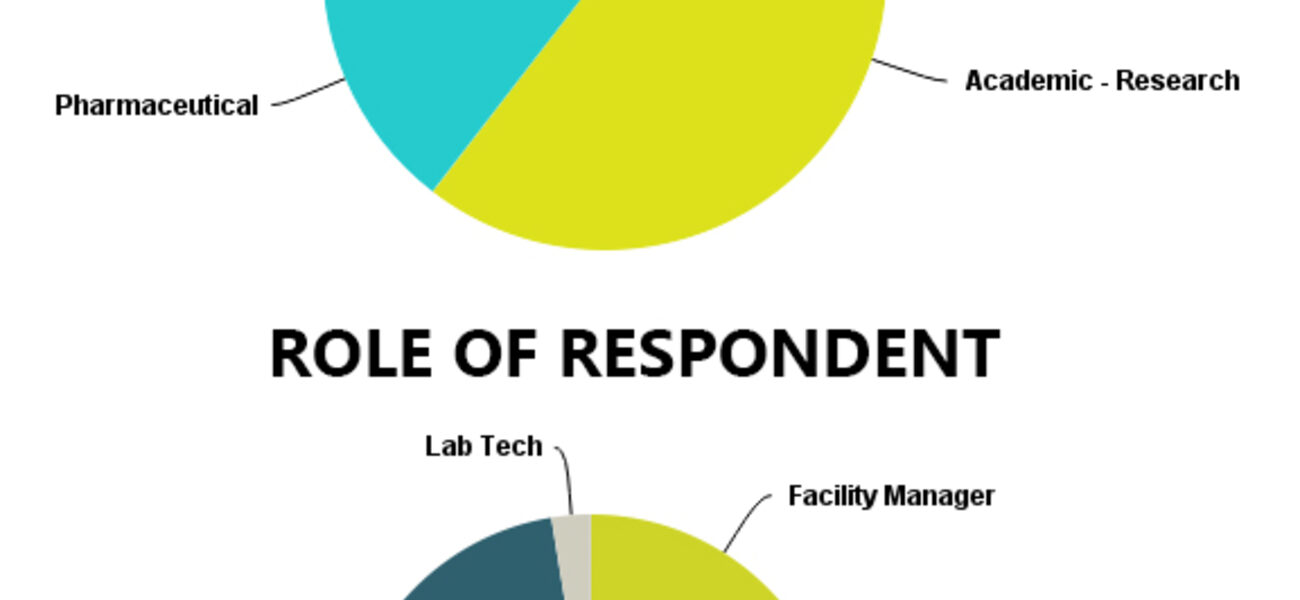

Survey respondents included members of the academic research sector, as well as pharmaceutical and biomedical researchers. Approximately two-thirds of the respondents reported using an open lab plan, while one-third were in closed labs.

Open labs are characterized by open floorplans, intermingled user groups, shared resources, modular mobile casework, and flexible service connections. Discrete or closed labs can be defined as labs with a clear user identity, where separate spaces are assigned to specific users or teams, and more resources are kept separate.

Open vs. Closed

“We found that most of the respondents working in an open lab environment feel that it does promote collaboration,” says Doran. “They also feel it is successful when you’re trying to share resources—especially more expensive equipment.”

However, while the data presented a mostly positive view of the open lab, when asked to list the pros and cons in their own words, survey responses weighed more heavily on the con side.

For example, one facility manager from the biomedical sector responded: “I absolutely hate the open lab design. It presumes that all different types of science can be done on benches of the same size. We have to fit our work to some generic footprint rather than create space that works for the science.”

Another researcher from the pharmaceutical sector replied, “We have a mixture of both styles, and I am not a fan of the open lab portion. I think the work that needs to get done gets done independent of the lab design. Researchers who need to work together do so whether or not their labs are separate or joined.”

Another respondent replied: “There are problems with personalities who are not good lab citizens—leaving shared resources unclean, borrowing items without permission, and not returning them promptly.”

“On the flip side,” says Doran, “we received several comments praising open labs for the ease of exchanging ideas with others and fostering teamwork when you have the right group of users. So if we were to simplify what makes an open environment successful, we really have to say it is all in the people.”

In a surprising contrast, when similar questions were asked of users who work in discrete or closed labs, virtually all of them felt that having their own dedicated space was beneficial to their work. A majority of respondents in closed labs also felt that collaboration with other groups was necessary, but did not find it difficult to work with others, despite the fact that collaboration becomes a more deliberate or planned activity. A majority also stated that they successfully rely on shared equipment and other resources.

“This was one of the most interesting data points for us,” says Doran, “because so often we use ease of collaboration and shared resources as the main selling points for an open lab design.”

Notably, much like the open lab users, 80 percent of the discrete users are doing their data recording and computer analysis at workstations in the lab, not separate from the lab.

“We found that they really struggled to come up with cons for the closed lab layout, and I would say that 80 percent of those cons were about personality,” says Doran.

Collaboration and New Workplace Design

The idea of creating spaces where occupants are encouraged to interact is a common feature in designs bearing the label “lab of the future."

“One of the key issues is how do you get natural collisions and collaboration?” says Jacobs. “Collaboration is clearly something we’ve wanted for a long time, but just because you put collaboration on a drawing, doesn’t mean people collaborate there.”

One approach is the concept of “new workplace” design, where seating is unassigned, and having a higher position or title doesn’t mean getting a bigger office.

“Decoupling space from status is really what new workplace is about from a very simple viewpoint,” says Jacobs. “For instance, where we have renovated offices at the GlaxoSmithKline facility in Parsippany, N.J., no one gets a desk. The vice presidents don’t have offices. They have a big kitchen table. The only people with assigned cubicles are just a few of the administrative assistants. There are huddle spaces and focus rooms, and you come in the morning and find a desk. It is a very radical change. Not only is the collaboration great, the square footage per person costs get driven down a lot.”

“Even though these users may be saying that collaboration is not that important to them, you still have to provide spaces like that,” says Doran. “Even if they are rebranded as a break room or a kitchenette, which seem to be much more functional collaboration spaces than throwing in a little lounge and saying ‘meet here.’ It is really about balance.”

Flexible Modular Furniture

Only about 25 percent of the facilities in the survey utilize mobile or modular casework versus traditional fixed casework, with a majority moving things a minimum of once per year. Additionally, more than 60 percent stated that they are using overhead carriers with highly favorable results.

However moveable furniture and partition solutions can also come with complications, such as discontinued parts or long lead times.

“At Princeton University, we’ve run into problems where the partition they chose about 12 years ago has been discontinued,” says Doran. “It’s fine if they want to demount a partition and be done with it, but we’ve been trying to renovate some spaces where we’ve had to take the partitions down and work with the pieces we have in order to create new spaces somewhere else. The other complication is that the foam gasket between these partitions breaks down over time, so you can’t reuse that part. It has turned into a headache for them, because these partitions are used throughout every lab in this particular building.”

Likewise, at the University of Pennsylvania, getting a new piece of casework for the modular system they’ve chosen for one building in particular can take 14 to 16 weeks, because the manufacturer doesn’t keep all of the pieces in stock.

“Situations like that are frustrating, because these systems are billed as a quick-fix solution for a renovation,” says Doran.

The Future is Balanced

Natural light and views to the outside were the two big winners when researchers were asked about their “wish list” for future lab spaces. The other common things on the wish list were energy efficiency, environmental sustainability, and close proximity between labs and office spaces.

One finding seems to contradict the interest in sustainability, however. While more than 70 percent of the respondents use filtered fume hoods, about 60 percent of those hoods don’t incorporate automatic sash closers.

“To us, one of the most interesting results was that the majority of research facilities are not instituting training with regard to the energy-efficient equipment and features built into their labs,” says Doran. “Our feeling is that if users don’t understand how to use the energy savings solutions, they can’t help but be part of the problem.”

“They were only somewhat interested in things like flexibility and equipment sharing, and most surprisingly, they were least interested in having space dedicated to collaboration,” says Doran.

According to Doran, the new lab of the future will be highly electronic, with abundant work space and monitoring systems to maintain shared equipment and resources, while office and desk space will be closer to the lab.

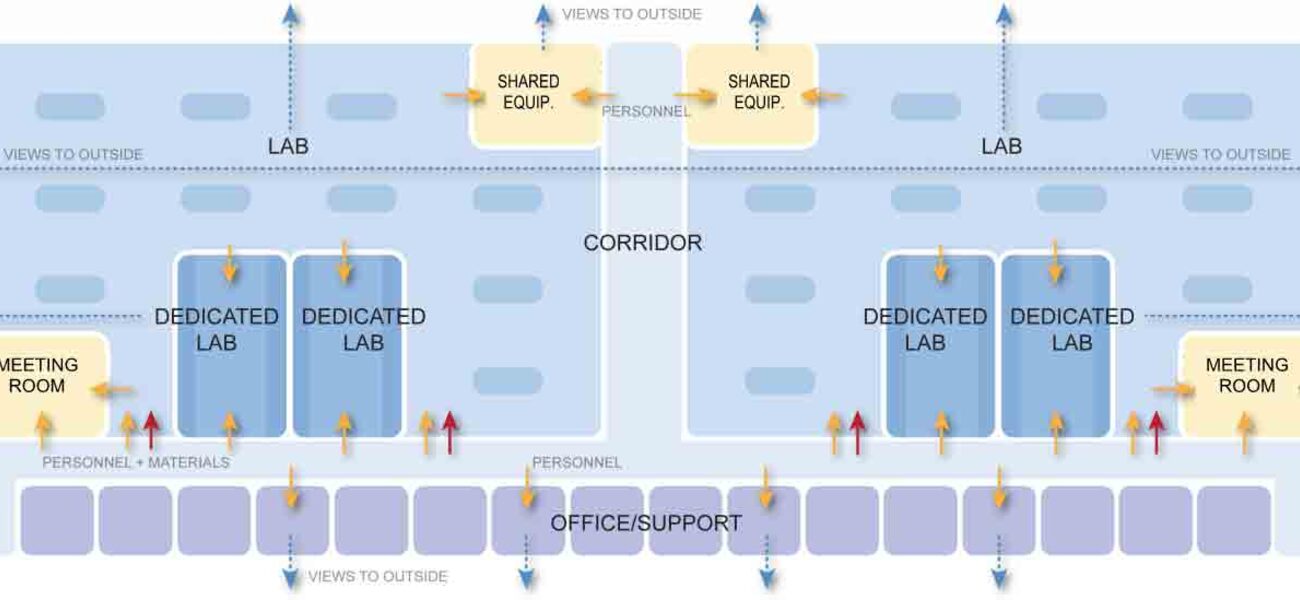

“We are beginning to form a clearer picture of what scientists and facility mangers want the new lab of the future to look like,” says Doran. “When function and finances allow, labs should have abundant natural light and views to the outside. The building core should be reserved for circulation and services, so the perimeter can be dedicated to the spaces that are occupied the most—which are labs. Better still are lab spaces that have end-to-end views to the exterior.”

But more than anything, the lab of the future requires a balance of features.

“One lab design typology shouldn’t be applied to all research groups within the same facility,” says Doran. “It’s not open. It’s not closed. It has features of both. Having the open lab is still a very good thing for cross-pollination and collaboration, but that has to be balanced with more closed space, so when somebody is working on something where they need their own space, there is an option for them.”

By Johnathon Allen