The Shared Resource Center, which will provide new lab space for four existing core facilities at the H. Lee Moffitt Cancer Center & Research Institute in Tampa, Fla., is nearing completion with substantial buy-in from staff, despite a sometimes challenging consensus-building process, according to Moffitt’s Christine O’Connell, senior director of laboratory research operations and Susan Constable, manager of shared resources. Working hand-in-glove with the project’s design-build team of Gensler architects and DPR Construction, O’Connell and Constable shepherded core facility scientific staff from skepticism to anticipation of the new shared facility, which will consolidate Moffitt’s existing Proteomics, Flow Cytometry, Molecular Genomics, and Translational Research cores. Constable and O’Connell cite three primary drivers for success: listening to users’ needs and concerns, using visual means to communicate design ideas, and knowing when to compromise and when to stand firm.

The impetus for consolidation is a familiar one: Over the years, space constraints and fixed benching in Moffitt’s laboratories had necessitated placement of many key pieces of instrumentation wherever they could be squeezed and plugged in, resulting in cramped workspaces, make-do workflows, and inefficient circulation. When an old vivarium became available for remodel, Moffitt decided to bring several lines of inquiry together in a flexible and open new environment. While some staff reacted to the change with indifference, many expressed concerns about noise and privacy, or questioned if consolidation was either necessary or beneficial.

Listening in Earnest, No Matter How Many Meetings it Takes

One central concern of core facility members was that in relocating these four cores to the new Shared Resource Center, those research faculty and staff would have to travel among two or three buildings to access the cores. “Our visioning session called for a ‘Showcase for Science,’ but the space available felt more like a bunker,” says Gensler project manager, Dawn Gunter. “Getting buy-in from the core facility scientists was a key part of making the project a success. It is important to make the scientists valued and integral contributors to the success of the final product.” To counteract the “bunker” fears, the design team created a transparent, branded entrance for the core facility. This was the first time the Moffitt has brought their core teams together, and it was important for them to have a distinctive space.

Initial discussions focused on the design team acquiring intimate knowledge of individual labs’ workflows. “We spent hours observing and talking with the researchers to understand why they worked the way they did, and what we found was a prevalent attitude of ‘This is the space, we’ll just make it work,’” says DPR project executive, Barry Cole. “If (benches) are fixed, that can create inefficiencies.” As the design team listened and learned, they also pointed out that the new, modular environment would provide an unprecedented degree of flexibility.

“They came to understand, hey, I’m getting a new piece of equipment. Right now the knee hole is on the right, and I need it on the left. I don’t have to get a new bench in here; we can just shift the base cabinets,” says O’Connell. Critically, the Shared Resource Center’s design leverages overhead panels for power and data, so that new or upgraded equipment can be sited in a number of different locations, depending on its size and purpose.

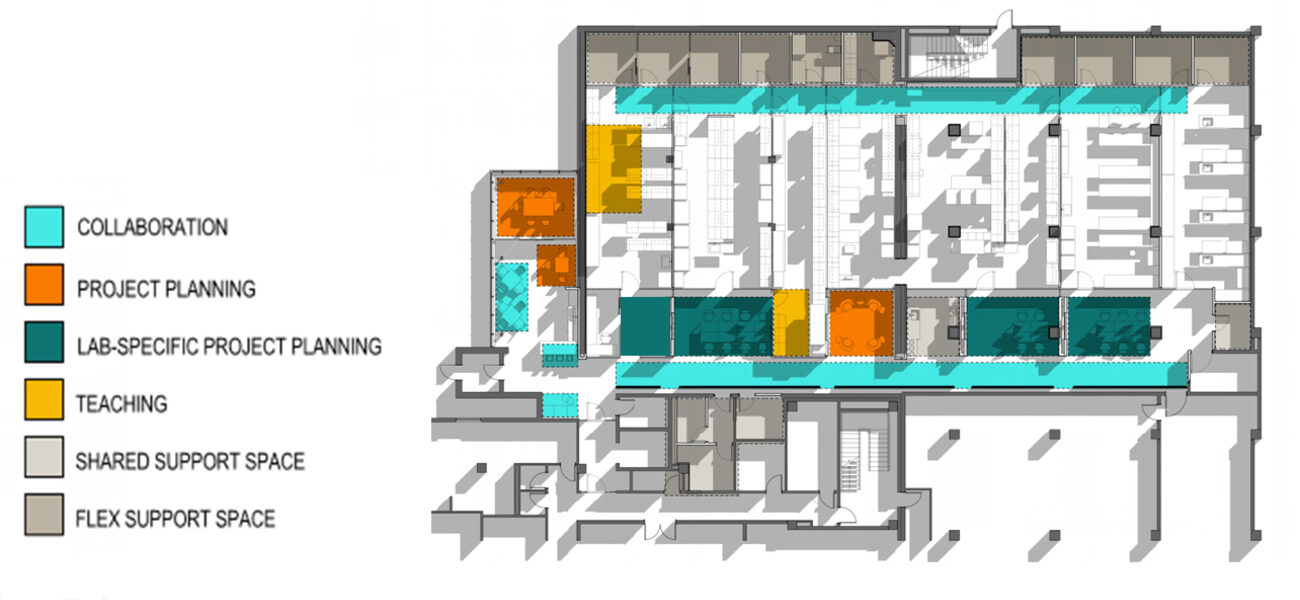

Another concern expressed by reluctant staff centered on noise and other disruptions. “You want people to feel that they are in a stable space that supports focused work,” says Gunter. “That’s critical for analyzing data and synthesizing multiple points of data obtained through core lab analysis.” The new facility provides places for project planning, lunch, and meetings. Noise was a very real possibility, as was distracting foot traffic. The front project planning areas, backed with 2.5 inches of acoustically absorptive material, were designed as touch points for meetings with research faculty and staff. The desire for openness and daylighting is balanced with the need for quiet concentration by an architectural treatment that breaks the facility into a series of independent spaces.

“You can do white-boarding here, roll some chairs over, and talk about the latest experiment and the next steps with research scientists,” adds Gunter. “Then you can go back to a lab that supports what you need to perform your protocols.” A private meeting space for confidential discussions is also part of the program.

One last concern was how to accommodate vendors. “It’s critical to have vendors meet with the scientists, but you don’t necessarily want them meeting in your lab,” says O’Connell. A “genius bar” in the café provides the ideal space for these meetings.

Speaking Scientists’ Language Rather Than “Design-ese”

It became clear that the designers needed to show the researchers what they intended to build, rather than just describing it to them.

“We had gone in talking about collaborative environments in science, but that didn’t resonate with them,” says Cole. Instead, the project team used visual means to communicate design options, including three-dimensional Revit® renderings.

“Working with (the scientists) in 3-D was really nice, because, well, they’re not architects. Looking at plans, many people don’t quite know what they are seeing,” says Gunter. “On several occasions, when we got pushback about the way we were approaching the design, we could show it to them in three dimensions, and we would work collaboratively to create a space that met the needs of both their scientists and their equipment flow.”

One turning-point meeting involved the finishes for an area intended for use by a group of five PIs. The design team presented two palettes—one high-contrast, with a “tech” vibe, and the other softer and more nature-based. To the surprise of O’Connell and Constable, the group went into detail about their preference for the more muted palette, describing the way they anticipated a “beachy” environment would make them feel. “It was totally unexpected from a bunch of scientists,” says Constable. “But you could tell that they were flattered to be consulted. I think that was a big step in getting them excited about the new space.”

Gunter describes the meeting as a threshold for getting buy-in and ownership. “They were talking about how relaxing the palette was, and clearly we didn’t expect that. It was a lot of fun for the scientists and very insightful for the design team,” she says.

When to Bend, and When to Stand Firm

Overall, scientists are focused on delivering compelling research within the space they are allotted, and may find disruptions to their routine threatening. “They were really traumatized by the fact that you weren’t going to go through a door to get into their space,” says Gunter. “We tried to explain that the activated corridor and the workstations were driven by the program exceeding the available space. Eventually, leadership had to step in and say, ‘Listen, this is how it has to be. But we are absolutely going to make it work for you.’”

“We did a lot of work to get buy-in, and then at some point, the answer is the answer is the answer,” says O’Connell. “If they said, ‘I need this wall to move, and this has to happen, and this has to happen,’ we worked with them really closely to help them understand how they could fit their lab into this modulated series of systems.”

The hard line was driven by Moffitt’s desire not only to consolidate, but to free up the cores’ previously occupied areas as recruitment space for new PIs. “The core facilities were landlocked—they had no space where they were. So we looked at this as a win-win, one for recruitment and two for giving the core labs additional space,” says Constable.

“They could say, ‘Well, I don’t want to go,’ but ultimately they were going,” says O’Connell. “The buy-in point was ‘I will be moving, so what is the best thing I could do to get the space the way I’d really like it?’ Certain cores were worried about losing square footage, but we could counter that with, ‘You might be decreasing actual square footage, but look at the degree of flexibility gained.’”

Despite all of the team’s efforts, there is one lab that still remains skeptical. “She was concerned about a slight decrease in square footage, but we were able to show that she will have a substantial increase in effective bench lengths,” says Cole. “She’s still hesitant, but I will say that she is extremely engaged now and wants to know when her space is going to be ready.”

Move-in is currently scheduled to begin in December 2015, and the team is confident that once operations resume, even the most recalcitrant users will be won over. “We’ve got concrete walls, so we are limited with our available space. The question becomes how to use that space and layer on functionality,” says Gunter. The modular bench system, project planning areas, genius bar, meeting areas, and café are all improvements to the discrete way the cores have functioned to date. So while “collaboration” is not quite the rallying cry the team had hoped it would be, “At the end of the day, it is creating those opportunities to meet with the research faculty and staff, to meet with the vendors on a regular basis, in a way that supports how these researchers do science.”

By Liz Batchelder