Research confirms that active and engaging university classrooms improve learning outcomes, but what features produce the most positive—and cost-effective—results? Surprisingly, perhaps, advanced technology is not nearly as high on the list of success factors as whiteboards, flexible furniture, and other space-related amenities.

Over the past seven years, George Mason University has explored several different ways of configuring active learning classrooms (ALCs) in a series of renovation projects on its flagship Fairfax, Va., campus. It has built an organizational structure to examine the space needs of 21st century learners and established an assessment group to focus on the most effective features with the highest return on investment. It has also developed an iterative design process, a short cycle of improvements that can be deployed relatively quickly, to allow faculty members to experience the benefits of the more flexible learning environment.

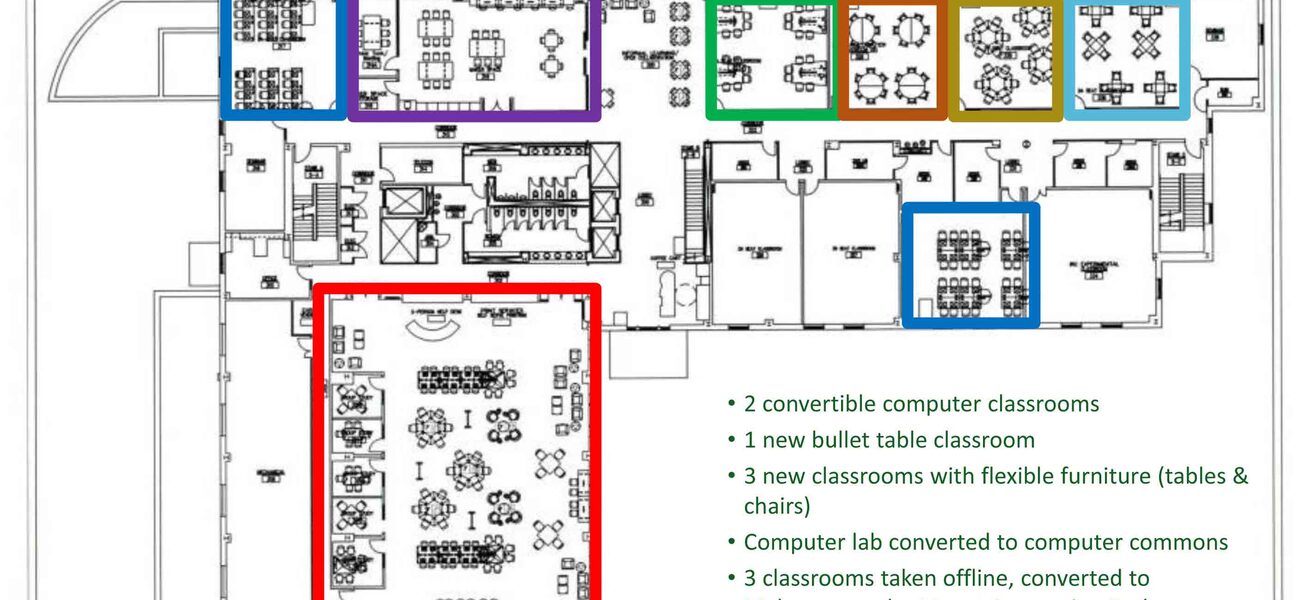

Having grown from 3 million sf of usable space in 2004 to 8.6 million sf in 2015, Mason is now looking closely at how to make sure that space is appropriately configured for innovative learning, identified as the top goal in the university’s strategic plan. The plan sets a target of 25 percent of all learning spaces devoted to active learning by 2024, a considerable jump from the current 6 percent ratio.

“This is a significant goal that has substantial cost impacts from both space and first-dollar perspectives,” says Cathy Wolfe Pinskey, George Mason’s director of campus planning. “Every expenditure has to have some sort of a return. Every single space decision is based on answers to questions like: Is this a space that inspires our students and faculty to be creative? Are we able to attract new students? Are we able to compete in a very competitive marketplace?”

The First Sandbox

Mason’s first step towards active learning was the 1,100-sf Room 215G in Innovation Hall, in 2008. The $100,000 “sandbox” project turned an underutilized computer training lab into a 36-seat ALC with movable chairs and tables and a mobile podium, “a big change for us,” says Pinskey. The technology, described as “a combination of high-tech and low-tech,” cost $58,000, an average of $1,611 per seat.

The renovation offered a startling lesson on the number of seats the reconfigured classroom could accommodate.

“We went from a space that averaged between 15 and 18 sf per seat to a space that was about 30 sf per seat,” says Pinskey. “The big question became how to achieve the lower density rate in a no-growth environment, using only existing and in-process buildings.”

Organizational Structure

The Room 215G sandbox experience also revealed that curriculum and instruction differ considerably in the active learning setting from the standard model with an instructor at the front of the room. With multiple small classroom renovations and technology refreshes on the horizon, Mason created two new groups, the Learning Environments Group (LEG), and a subset, the Learning Environments Assessment Group (LEAG), to gather appropriate and effective information for planning and to make learning spaces more successful through the iterative design process.

LEG is comprised of approximately 15 stakeholders from across the university, meeting monthly to conduct sustained conversations on active learning, rather than simply focusing on individual projects. It is co-chaired by a member of the campus planning staff and by the director of the Center for Teaching and Faculty Excellence, which provides leadership in promoting, supporting, and celebrating educational excellence inside and outside the classroom. LEG members represent a diversity of perspectives, from faculty and students to IT and the registrar’s office.

The smaller LEAG is staffed by the Office of Assessment, the Center for Teaching and Faculty Excellence, and the campus planning group.

“We created a protocol for assessing the new rooms, including questionnaires, surveys, and observations made by graduate students hired specifically for that purpose over a full semester,” explains Pinskey. “Along with training for faculty occupants, the group conducted pre-surveys about how faculty thought they would use the room, including technology, versus how they actually used everything once in the room. This way we learned what was making the biggest impact and what wasn’t, the basis of our new iterative design strategy.”

Rave Reviews for Flexibility

Gleaned through both observation and research, findings from the various iterations indicated that the most popular features were whiteboards, flexible furniture, and a space configuration that affords abundant opportunity for faculty and students to move around and engage in different activities within the room.

Two ALCs in particular drew great reviews from both faculty and students, specifically for their flexibility. All tables and chairs are on wheels, thus reconfigurable. The chairs can be rolled away and stacked when not in use. Trapezoid or half-round tables can be arranged in half or full circles or in rows. The podium and AV cart are also on wheels, with an umbilical cord to connect technology devices anywhere in the room. The whiteboards are also mobile: At 24 by 36 inches, they can be carried around, placed on tables, or rested on the multiple ledges that line the room.

To encourage faculty to envision how the ALCs can be rearranged, the planning team provided cues in the form of diagrams depicting different furniture configurations. The cues have been effective in inspiring different set-ups.

Simplifying Technology

As a result of lessons learned from previous iterations, Mason scaled back the technology set-up in later ALCs, considerably lowering costs in the process. An earlier design, configured for 72 seats, featured a large central projection screen, with several smaller, wall-mounted screens spread around the room.

The system could display different content on different screens, but the process was complicated, and “faculty don’t want to be stymied by complicated technology in front of 72 students,” observes Pinskey. Training on the equipment was provided, but instructors didn’t always know how to use it until they were assigned to the classroom.

“Do we really need to be spending money on complicated technology with bells and whistles if 70, 80, or 90 percent of the time it isn’t even going to be used within the space?” asks Pinskey rhetorically.

Simplifying the digital set-up in later ALCs contributed to a significant reduction in the technology spend. Mason’s cost went down from $1,600 per seat in the early sandbox to between $700 and $800 per seat in some later rooms, a much more attractive price point.

The voice reinforcement scheme trialed in a larger classroom also turned out to be problematic. Because of the room’s size, microphones were necessary for students to be heard even from table to table. There were three mics per table, and the controls were awkward to manipulate. Students could cut each other off if they activated their mics at the wrong time.

“It was hard for both faculty and students to acclimate,” says Pinskey. “When we think about this again, for another large room, we will look for a more user-friendly system.”

Others’ Experiences

George Mason’s experiences parallel the conclusions reached by Robert Beichner, Ph.D., Alumni Distinguished Professor of Physics at North Carolina State University. Beichner is a pioneer of the SCALE-UP (Student Centered Active Learning Environment with Upside-down Pedagogies) concept, which shifted from instructor-centric teaching to facilitate students working together in small groups.

“You need to have students teaching each other,” he says. “When they work together on projects, they use the same vocabulary and have the same cultural touchpoints.”

This emphasis on promoting student interaction led Beichner to identify the table as the most important ALC component. Whether round, hexagonal, D-shaped, or trapezoid, each table should accommodate what research has shown to be the optimal size instructional group, three to four students. This generally translates to 7-foot round tables that accommodate three groups of three. Smaller rooms can be outfitted with smaller tables that each fit two groups of three.

Beichner’s experiences reinforce Pinskey’s views toward technology in the active learning classroom.

“Many kinds of computer technology have been introduced to make the space more exciting, for example, technology that allows students to swap or distribute files, or select different screens to project,” he says. “But the more complicated it is, the less likely it is to be used. Smart boards are rarely used as anything other than white boards.”

The University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, has gradually been deploying active learning classrooms since 2007. The rooms are a modification of SCALE-UP and the Technology Enhanced Active Learning (TEAL) concept that originated at MIT. Currently, the university has as many as 16 active classrooms (depending on configuration), the majority of which are located in its newest building, Robert H. Bruininks Hall.

Using an adaptation of the Projection Capable Classrooms (PCC) technology system, the ALCs are equipped with round tables that accommodate nine students each, with display connections for devices in addition to WiFi; multiple flat-panel display projection systems; and a centered teaching station that allows selection and display of table-specific information. Most of the classrooms have wall-mounted white boards, but three are outfitted with a 360-degree glass-surface marker board.

“We'd use the glass marker boards in all ALCs but the budgets at the time of Bruininks Hall construction didn't allow for it,” comments John Knowles, instructional technology coordinator.

Knowles notes that there have been only minor changes to the design since the first two pilot classrooms came online eight years ago.

“The original pilot had a solid round table, but we switched to tables divided into sections so groups can split off and reconfigure,” he says.

The display monitors were also repositioned. At first, they were hung above the white boards, but that proved too high for comfort. They were lowered in subsequent fit-ups. Knowles notes that the placement does take away some writing space on the white boards, but “the monitors are now much more usable.”

Another change was the addition of microphones at the tables, along with up to four wireless mics in large classrooms with multiple instructors. In a room with 171 seats, this audio capability is essential, Knowles points out.

A key to success is that students are comfortable and familiar with the technology.

“There is a mic etiquette,” he explains. “In a large room with a lot of tables, you don’t instantly know who’s talking. The speaker has to identify himself, so everyone, including the instructor, who might be at other end of room, knows who is talking. This is a very good way to encourage student participation.”

By Nicole Zaro Stahl