Whether personal or professional, change evokes an emotional response. Workplace change initiatives, especially those relating to space, nudge (or jolt) employees out of their comfort zones and typically entail some modification in routine and behavior. Relationships change, as well, and questions arise about how to continue performing at a high level in the new environment. The fastest, most productive change strategies take these human dimensions into account.

“Organizational and/or space changes are very emotional for users,” says Adam Griff, director, brightspot strategy, a New York City-based change management consultancy. “If you don’t recognize and address that at a qualitative level, and display understanding and earn trust, all the rigorous quantitative and metric-driven analysis you do will probably not be enough.”

Change Response Spectrum

The first step in designing an effective change management strategy is understanding that not everyone will have the same response. Griff cites the work of sociologist Everett Rogers, known for segmenting people into five categories that reflect their relative receptivity to change, across the spectrum from fast to slow: innovators, early adopters, early majority, late majority, and laggards.

“In any change management program, you are never going to flip a switch,” says Griff. “Every organization is going to have people in those different groups.”

The change initiative has to be structured around the fact that adoption will take longer in some groups than others. The process can be accelerated by an approach that engages users in the change. While not everyone will move into the early adopter category, Griff notes that a well-designed initiative can shift the slower groups in that direction, so adoption occurs more quickly.

Five Factors of Adoption

Rogers’s research defines five factors of adoption that advance this shift. The first three have to do with making the change tangible and transparent:

- Observability: Is it visible? Can I see someone use/interact with it?

- Trialability: Can it be tried or altered? “It is even better if you can play with it,” says Griff.

- Complexity: How easy is it to understand? “The more intuitive it is, the more willing people will be to try it,” he says.

Factors 4 and 5 relate to the personal impact of the change:

- Compatibility: How compatible is it with the way I am already working and the tools I like to use?

- Relative advantage: Will there be a net gain for what I need to do?

“In our business, talk about change refers to organizational change,” says Griff. “But for each employee, it is going to be about how he or she will be affected individually—user by user, person by person.”

Participatory Design

The most effective change strategies integrate change management into the design process, instead of segregating it in two separate tracks. Blending the five factors of adoption into the design process creates what is known as “participatory design,” a process that genuinely engages users and gives them a sense of ownership in the outcome.

Underlying this success is the principle that people adopt the change they shape. While issuing the caveat that the process is never perfect, Griff notes that involving people early in the initiative, in a tangible way that allows them to experience the benefits, gives them a stake in the outcome, with the result that they will adopt the change.

“When participatory design really works, you are actually teaching people to become researchers and designers themselves,” says Griff. “They engage equally and fully in the process with your professional consultants, your architects, with leadership and management.”

The participatory design process unfolds in four stages—understanding, visioning, planning and prototyping, and implementing—some of which can proceed in parallel. Brightspot has developed methods and tools for each to promote deeper engagement and hasten adoption.

Stage 1: Understanding

Understanding obliges users to recognize the current state of their space and how they work in the organization, with a focus on identifying key activities and moments instead of spaces and features. This empowers them as co-creators contributing observations gleaned from their own discoveries.

One helpful tool is the “service safari,” which sends employees out of their own workplace to observe space and service delivery models in other environments. As part of a renovation and change management project in the New York Public Library system, Billy Parrott, managing librarian of Art and Picture Collections at the mid-Manhattan branch, went on a few service safari excursions that had small staff groups visit roughly 30 different locations, from museums to retail stores to coffee shops. Their focus was on understanding and documenting different service experiences and then thinking how they might apply to libraries.

“The safaris helped us pinpoint what we liked about various places, what entices and gets us engaged,” says Parrott. “We tracked the workflow, how the customer service experience moves people through the space. What are the first things customers do and see, what’s next, at what point do they interact with staff?

“This helps us re-envision our service points and figure out the best ways to meet the needs of our library patrons. It also helped me visualize how to attract new users,” he says.

While the safaris are a classic example of “seeing is believing,” they also make a larger contribution.

“When employees see these things for themselves, it is so much more powerful than simply showing them data,” says Griff. “Not only will they become better partners because they are more attuned to everything that is going on in their space, but they will also provide more specific and direct feedback, so you can better design the space for them.”

Stage 2: Visioning

The visioning stage moves the focus on understanding the current state to envisioning the destination. It involves collaboration among several groups and at several levels. IT and space should always get together at this stage, advises Griff.

The vision is created in a bi-directional process, from the top down and the bottom up. Depending on how hierarchical the organization is, leadership involvement in the visioning sessions may be more or less frequent. Griff does recommend that management and frontline staff come together when envisioning the service delivery experience.

“Oftentimes the frontline staff will have much more insight into what the users need,” explains Griff. With their first-hand knowledge, they can point out operational implications of a particular vision, for example, training and infrastructure considerations.

He adds that visioning is more than a metric; it’s a goal.

“Visioning is a story, not just a strategy,” says Griff. “Stories are very powerful to move a whole organization forward and together. You have to think about the story you are going to tell.”

Stage 3: Prototyping and Planning

Griff places heavy emphasis on coupling prototyping and planning activities. Getting an early start allows for inevitable course corrections. “No matter how much research you do, you will never be able to anticipate all the implications of a change.”

Prototyping is the best way to make the change observable and tangible. Users who have a chance to try it out in on-the-job experiences can see the benefits for themselves and provide better feedback. It can take place at varying levels of simplicity and fidelity.

Experience mapping, where users provide feedback as they trace their typical daily journey on a floorplan of the space, is a simple prototype. Rehearsals and scenario exercises step up the complexity, while a full-time pilot with real users is even more elaborate.

In a pilot for Planned Parenthood’s corporate offices, the goal was to connect managers more closely to their teams by bringing them out of private offices into an open, collaborative layout. With advance notice to the staff, the landscape underwent a dramatic change over a weekend: Private offices were converted into meeting rooms, and the desks were moved to the open, window-lined floor area.

Griff notes that people bought into this seismic shift because they were assured that it could be undone, revised, or refined to respond to their needs—for instance, creating spaces for managers to hold private or confidential conversations or perform head-down work.

“The way you get people to plunge in, trialability, is by telling them this isn’t going to go on forever,” he says. “We will try it for a short period of time, objectively collect data, and discuss results. Let the chips fall where they may.”

By focusing on results, rather than personal or hypothetical considerations, this approach increases buy-in, reduces risk, and makes the change more appealing.

Planned Parenthood wound up keeping the new configuration.

“The experiment was a big success,” he comments.

Stage 4: Implementation

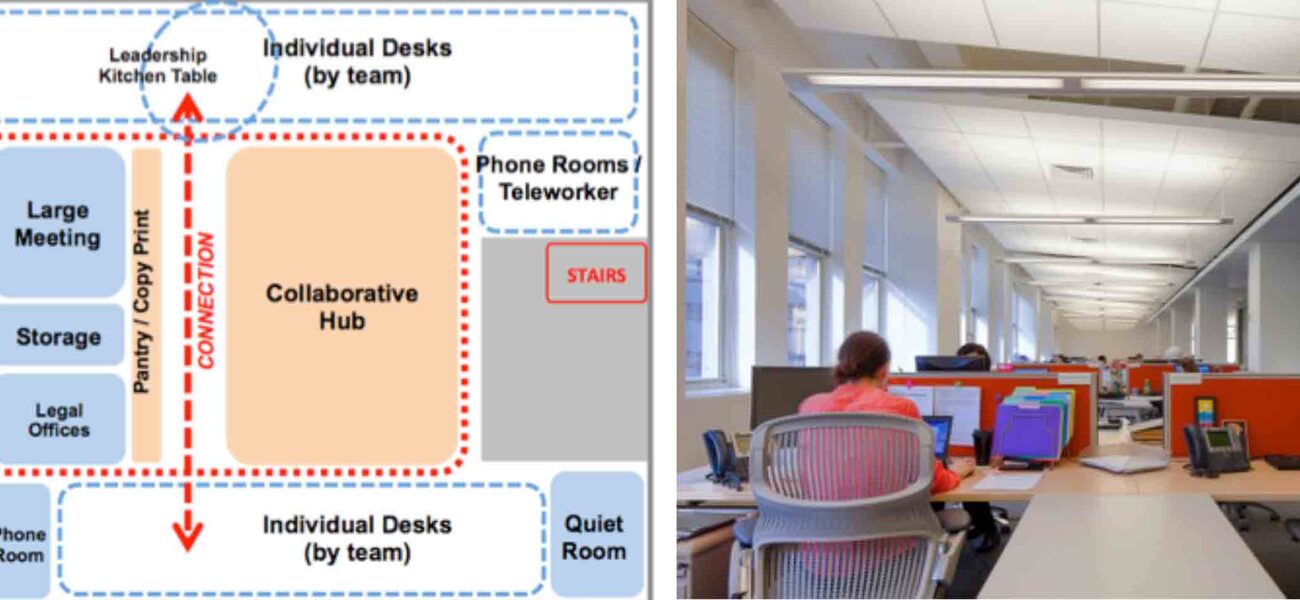

Griff illustrates the implementation stage with an account of the University of Minnesota’s Work+ initiative, another project on which brightspot strategy consulted. The goal was to promote alternative workspace strategies in new and renovated facilities. The first target was a demonstration project integrating all Office of Human Resources (OHR) departments, done in partnership with UMN facilities, construction, space planning, and the Office of Information Technology, which provided expertise and assistance. The OHR departments of Employee Relations; Compensation and Classification; Communications, Leadership, and Talent Development; Occupational Health and Safety; and Training Services were combined on one floor from several locations around campus.

Here’s how the Work+ story was presented: “The Work+ program integrates the university’s technology, training, and facilities expertise in a way that enables colleges and units to redesign their workplace into a variety of spaces…to be as effective as possible.”

According to Patricia Franklin, chief of staff of the OHR, the pilot unit for Work+, the nearly year-long process began with workshops to help the leadership team imagine new space and work possibilities. It continued through a series of large group gatherings, employee surveys, and discussions to document how people worked, and what their needs were, especially around technology. These were followed by branding, training, and an extensive communications campaign, in a multitude of formats, including regular newsletters, videos, and office hours Franklin scheduled for employee feedback and questions.

“Together with brightspot, we developed a very robust tool kit of all components going into the program, explaining the rationale, surveying workstyles, creating a validation process,” she says.

The Work+ environment is considerably different from what employees were used to. Private offices were eliminated; cubicle walls were lowered from heights of 9 and 6 feet to 4 feet; meeting spaces and temporary touchdown spaces were created to make employees more mobile. Essentially, the new landscape provides a variety of spaces to support different types of work, especially collaboration, quiet, and ad-hoc activities.

Among the issues addressed in the multiple change management sessions were workplace storage; managing flexible teams whose members no longer have a fixed location; training in new technology, like Google Hangouts, that enables employee mobility; and establishing workplace norms and protocols.

Observing that it can be “a hard cultural change to ask people to make,” Franklin reminded employees to think of their own space journey throughout their careers. “Things change, we’ve always been evolving,” she says. “This is a very helpful conversation to have.”

The post-occupancy evaluation revealed that satisfaction with the energy of the workplace doubled. The sense of “One OHR” increased, as did the perceived importance of working with colleagues. Staff spend their time differently, for instance, less at their desks and more collaborating informally. They are also saving time, including getting significantly more rapid feedback from peers and managers.

“The longer we’re here, I see greater comfort,” says Franklin. “Our new space lends itself well to the feeling of group ownership. It is flexible and adaptable, and people can shift the furniture around if they want.”

As the university moves ahead with other renovation and construction projects, Franklin foresees continued use of the program in redesigns that change the way people work.

“Utilizing this design philosophy and process, we have found we make better use of our space,” Franklin concludes, adding, “We’re not done thinking about this for our own unit.”

By Nicole Zaro Stahl