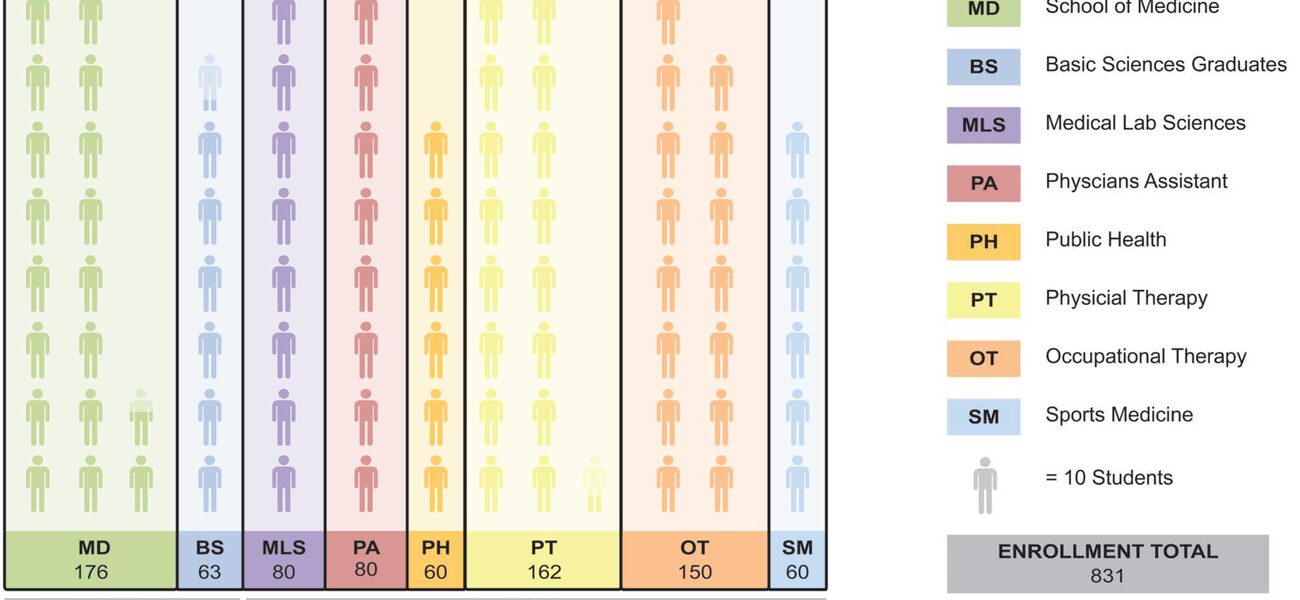

A new interdisciplinary medical and health sciences education building at the University of North Dakota (UND) has reinvigorated academic culture with shared resources and improved research capacity, while accommodating increased enrollment and faculty. The 325,000-sf School of Medicine and Health Sciences (SMHS) building replaces the repurposed hospital that previously housed medical education on the campus, bringing disciplines including medical lab sciences, physician assistant, occupational therapy, sports medicine, public health, and physical therapy together with medicine. The project offered tremendous opportunity along with the transition pressures to be expected from such a significant and impactful change.

The project team, consisting of JLG Architects, Perkins+Will, and Steinberg Architects, worked closely with Randy Eken, the SMHS associate dean for administration and finance, who chaired the building committee. The program, plan, and design for the SMHS evolved through an intensive visioning and change management process to become a new touchstone on campus for open, flexible research and interdisciplinary learning.

Challenging the Status Quo

The project’s top conceptual goals were identified early on: collaboration, health and wellness, flexibility, embodiment of values, welcoming, and identity, coupled with the desire to create an interdisciplinary hub, community asset, and “living laboratory” that would reflect UND as a health campus.

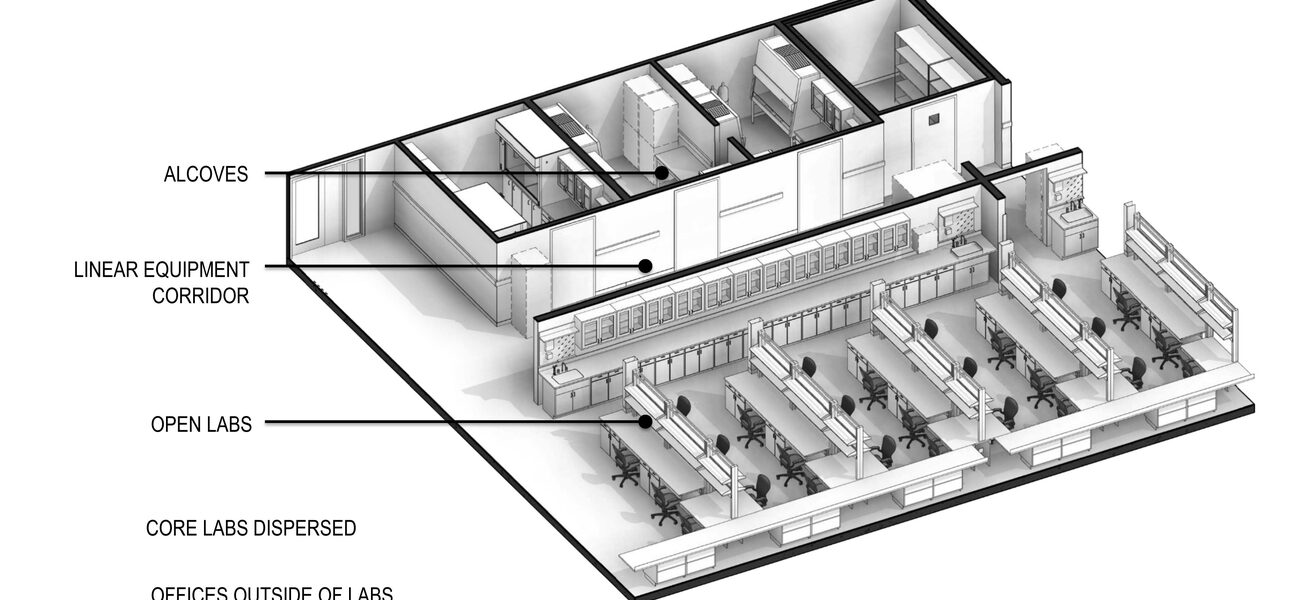

In three main areas, the status quo was underserving these goals. To fulfill them, the team focused on transitioning to interprofessional learning communities from knowledge “silos,” shared versus dedicated instruction space, and the creation of more open laboratories. “One of the big shifts was pulling together medical, physical therapy, and occupational therapy students from what had historically been disparate buildings on campus,” says Bob Lavey, who directed the project’s planning effort while at Steinberg Architects. “We wanted to cut across all these different programs and create communities—a great goal, but it was unprecedented. There were some concerns.”

Well-defined options turned out to be the key to consensus. “This was the question I focused on immediately,” says Eken. “The area being proposed—17,000 sf—was a lot to designate for what was essentially a brand new thing.” The team responded with three distinct plans, each with its own advantages. Plan A, the most progressive of the three, involved four interprofessional communities with two dedicated spaces and one shared, central social space apiece. Plan B examined scenarios that designated space to one or two programs. For example one learning community space could serve all of medical education while another could be shared by physical and occupational therapy. Plan C, which was reminiscent of the decentralized library spaces model seen in other projects, called for fully shared and flexible space throughout the building, which could be used by anyone. “The options were reassuring,” says Eken.

The heat was on to make early decisions quickly; the students that had already been admitted to UND for the fall of 2016 wouldn’t fit into the existing building. “Interprofessional learning communities were proposed in our second programming workshop. The A, B, and C options came up in our third programming workshop,” says Andrea Stalker of Steinberg Architects. “By the fourth, we had approval to move forward with Plan A: the interprofessional learning communities.”

The new interprofessional model was largely met with enthusiasm, although second-year medical students were among its biggest skeptics. “Medical students had been the only group of the eight different programs we were targeting that had their own dedicated student support space,” says Lavey. “They were naturally hesitant about moving from the old building where they had this owned space.”

Eken is circumspect. “The first-years who are in the building this year will already know what it’s like,” he says. “We are still getting the learning community organized because all of this happened so fast. But from our early observations, I think it’s going to work out just fine.”

A Quick and Collaborative Design Process

In bringing so many programs together for the first time, Stalker notes, “The university had an opportunity to rethink everything. We decided to take nothing for granted, but we knew that buy-in and consensus were crucial.” The design team cites early visioning and goal-setting, diverse user and stakeholder groups, and decision-making empowerment as three keys to success.

“Our favorite question to ask is, ‘What is the one thing you want this project to accomplish?’” says Stalker. The responses can range from the lofty to the mundane. “If they just need that sink in this room with this much storage, that’s perfectly okay. People can’t think about larger-order change until they’ve had the opportunity to tell you about their needs and wants. But we then ask how that goal aligns with the mission of the institution.” The lists that emerged were then distilled down to the top 10 guiding principles.

The process for the SMHS building included 178 users, drawn from departmental, collaborative, and building committee groups, who participated in 12 workshops and approximately 500 meetings over the course of one year. The School’s commitment to this demanding time investment for faculty and other stakeholders was a windfall given the aggressive project schedule. “It was somewhat overwhelming on paper, but we did it, and the project was better for it,” says Eken. “I think our group relished change, and we worked hard to get timely decisions made.” This decision-making empowerment ultimately allowed the project team to complete programming, design, and construction documents for the facility in a single year.

Clearing Change Hurdles

As it is at many universities, change is a sensitive topic at UND. Bob Novak of Perkins+Will describes transition management as the art of “taking the edge off” the kind of radical rethinking being undertaken at the university. “Going from a cast-in-place concrete 1950s building to a brand-new facility with natural light and open offices and laboratories can present a bit of a culture shock,” he says.

While the early design process involved many small groups, transition management focuses on decreasing any lost time and maximizing wide-scale satisfaction with the end product. “It’s a four-step process,” says Novak. “First, you create understanding, explaining the building in the ways it relates to them individually. Second, we work through experience scenarios. What is it like to be a researcher in the new building? What do you see when you walk in the door? Where is the coffee?” Building enthusiasm and excitement is also part of this stage.

The third stage is preparation, for both the actual move into the new building and for guidance and support afterwards. “We took this very seriously,” says Eken. “A lot of our people had been in their physical office spaces for decades.” The team developed committees to research aspects from phone lines to key access to “stuff” accumulated over the years, going so far as to develop individual office move packets. But personal accountability remained paramount.

The message was: “The architects and engineers will build us a new facility, but you are responsible for moving in. You each have to pack your office. You each have to pack your lab.” Eken himself attended more than 100 meetings related to the transition alone to drive this point home, knowing from past experience that “If moving into the building is a disaster, everything is going to be a disaster.”

Ultimately, the move-in process took 15 weeks, with care taken to accommodate grant-writing and summer coursework needs. “It wasn’t without some minor issues,” says Eken. “But you have to make a commitment from the top to make things happen.”

The final transition stage? Celebration! UND’s included about 400 people. “Once you get into the building, you have to celebrate,” says Novak. “It’s about awareness and orienting people to the new space, but also about creating a sense of occasion and welcome.”

Inspiring Early Days… and a Few Lessons Learned

While the core curriculum for the new building’s eight disciplines has not yet changed, UND has hired an associate dean for teaching and learning who is versed in progressive pedagogy and technology. The university is still developing guidelines surrounding common use areas, but results thus far are encouraging for the SMHS’s shared spaces. “It has created better teaching schedules and wider variety,” says Eken. All of the shared rooms can be scheduled online.

Whether to police use of the large meeting spaces is one issue still under discussion. “Because the building is so transparent, you can easily see when a meeting room is empty, and the students tend to just camp in there,” says Eken. “So there is some debate about that.” Currently, the university allows use of the meeting rooms for study time as long as they are not otherwise booked.

In hindsight, a committee devoted to technology might have further smoothed the path to success. “It’s one of those challenging subjects, and we don’t have it perfectly just yet,” says Eken. On the balance, however, the project has proven that big thinking can be fast-tracked with the right institutional commitment, design team, and internal consensus. “We thought, why don’t we ask for what we really need, and what is good for the state and the future? The result is a dream come true for a lot of us.”

By Liz Batchelder

For information about the genesis of this project, read this earlier Tradeline article. A more detailed look at the building itself can be found here.