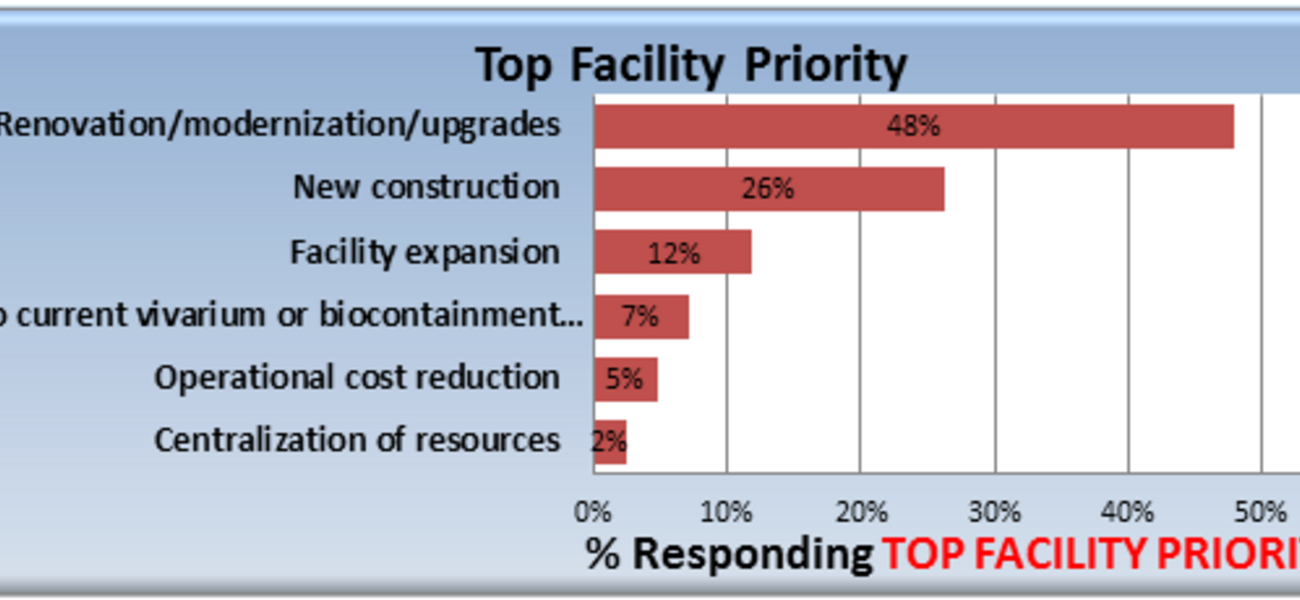

With many aging animal and biocontainment facilities coming to the end of their useful life, renovations, modernizations, and upgrades are by far the top priorities among facility owners and operators, and greater flexibility and adaptability are the hottest issues in project and program planning. Rodents are still overwhelmingly the primary species in animal research, according to industry leaders, and most containment facilities maintain a combination of containment levels; of facilities housing a single containment level, BSL-2 is by far the most prevalent.

“The vast majority of new opportunities over the past year are renovations or renovations with an addition,” says Jeffrey Zynda, academic science practice leader and principal at Perkins+Will.

“I think it’s simply a matter of dollars,” says John Bradfield, DVM, PhD, senior director of AAALAC International. “You might be able to garner enough to upgrade your HVAC or add biocontainment; people are holding onto older facilities and upgrading.”

Modernization projects are currently underway at the University of Pittsburgh’s School Medicine, for example, and at the Massachusetts Department of Health state diagnostic lab. And a small state rabies lab building is being constructed within a pre-manufactured metal building in New York State.

“Some of our clients are looking to add containment lab capacity because they’re at their limit, but we have not seen any large stand-alone containment facilities,” says Michael Walsh, PE, LEED AP BD+C, senior mechanical engineer and principal at R.G. Vanderweil Engineers, LLP.

Zynda concurs. “We are seeing a proliferation of containment facilities, but on a small scale, 400-500-1000 sf.”

“I’m seeing less focus on ABSL-3,” says Josh Meyer, AIA, managing principal at Jacobs Consultancy, Inc. “There are some projects from people already doing a lot of containment work who have experience in it, but I’m not seeing people jumping into it for the first time.”

“Biocontainment space is always in short supply,” says Bradfield. “The landscape of contemporary science is such that we’re likely to see more of a need for this.”

Indeed, there are still new facilities being constructed in the animal facility and bicontainment realm.

A major university in the Southeast recently issued an RFP for a large new vivarium building to be constructed in multiple phases, and Texas A&M is building an ABSL-AG from the ground up. A university in the Northeast is building a new animal facility with the capacity to function at ABSL-2 and ABSL-3, as part of a plan to relocate its medical school. The outlier, of course, is the National Bio and Agro-defense Facility, or NBAF, in Manhattan, Kan. That $1.25 billion large animal BSL-4 laboratory will open in 2022, replacing the Plum Island Animal Disease Center in New York.

New construction of several multispecies facilities are underway at two medium-sized universities in Canada, as well: A neuroscience-rich facility and a life sciences building, one floor of which will be an animal facility. And in the planning stages is a new Animal Resource Center at Memorial University of Newfoundland, where they also will break ground later this year on a 300,000-sf Core Science Building that will include a freshwater aquatics facility.

Renovation vs. New Construction

Almost half of the research organizations recently surveyed by Tradeline cite renovation, modernization, and upgrades as their top facility priorities. A variety of factors—compliance, cost, and a desire to consolidate—influence the decision to renovate an existing facility. Many buildings constructed during the biocontainment boom were designed under previous editions of the BMBL, ANSI, and CDC select agent standards, and their owners are looking to upgrade their facilities to comply with the new regulations. Other institutions are looking to consolidate, to make their existing facilities more efficient.

“Having animal rooms that are not fully occupied or at capacity is a huge cost,” says Walsh. “It’s a balancing act to maximize the use of the space you have.”

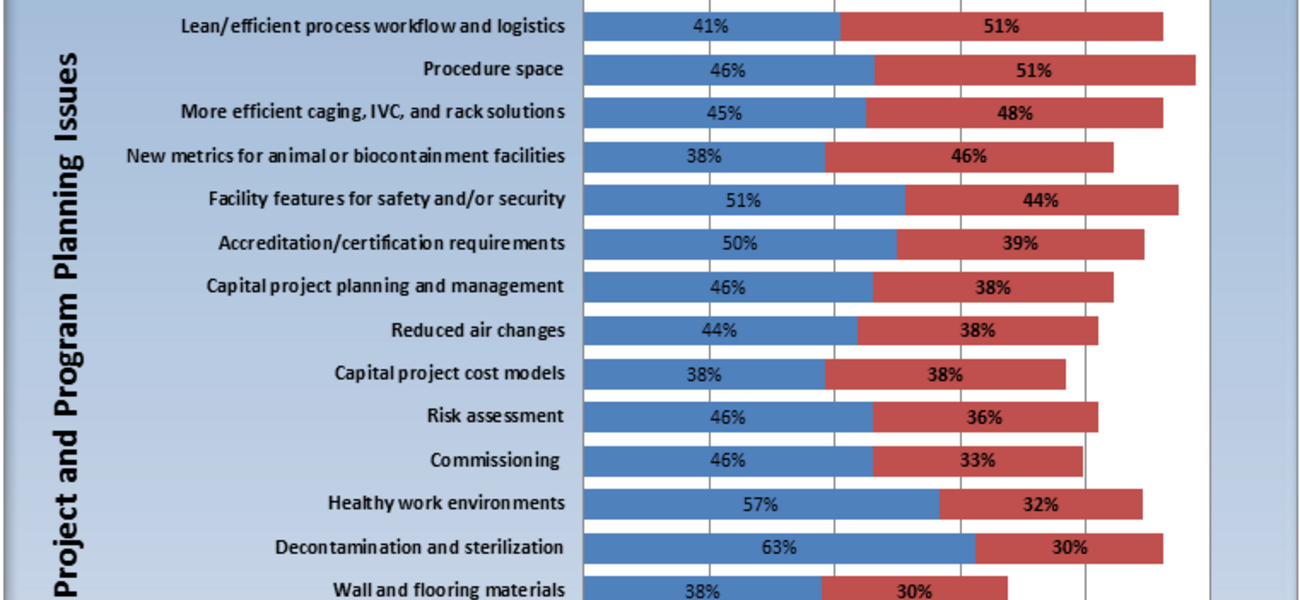

In fact, the second-highest project and program planning priority, according to the Tradeline survey, is increased utilization of existing space.

“The only way to cut per diem costs is to cut staffing levels,” says Meyer. “If you have multiple, small facilities, they are unbelievably inefficient. By and large they’re there for convenience, and I don’t know how much longer most of my clients can afford to provide animal facilities and put them where they’re convenient.”

Sometimes that convenience can be scientifically justified if a vivarium is close to a piece of equipment that’s too expensive to move, such as an MRI, he adds.

Evolving Variety of Animal Species

For decades, mice and rats have been the go-to species for animal research—they are inexpensive, breed quickly, and have generations of research behind them. That model is not likely to go away in the near future. But new technology and lines of research could tip the balance toward a broader variety of species, and institutions say their highest project and program planning priority is greater flexibility and adaptability.

With increased funding for neuroscience research, for example, investigators are relying more and more on zebra fish.

“Zebra fish are one of the most cost-effective models,” says Zynda. “We’ve seen a huge increase in the inclusion of, and interest in, aquatics.”

“If you bring a few researchers who need zebra fish into an existing facility,” says Bradfield, “it’s pretty easy to get that up and running on a small scale; often the researchers themselves manage it. Then they need more square footage, more support. Once they get their foot in the door, it tends to take off.”

Converting to aquatics from another type of animal holding room can be relatively easy, provided that certain features are in place.

“We are seeing zebra fish in almost every animal facility we do,” says Walsh. “But there are some specialized requirements for that—the structure to support the weight of the tanks, and critical life support systems.”

“We’re designing flexibility into the majority of our facilities, by putting floor drains in some of the small animal rooms,” says Mark Corey, AIA, principal with Flad Architects. “The floors do not necessarily have to be sloped to balance the functionality of the room with the future flexibility of it. All cages and racks have locks, so they can be on a sloped floor,” he adds. “It’s a pretty shallow slope.”

Floor drains are a source of contamination for rodents, so they need to be capped, and the traps need to be primed periodically.

“In addition,” cautions Walsh, “a lot of power is required for pumping systems. This is not a home fish tank—water is constantly being changed. They require big treatment and recirculating systems that use quite a bit of water.”

Some in the industry predict that the gene editing technology known as CRISPR/Cas9 could open the door to research models using almost any species, meaning animal facilities will need to accommodate species of all sizes.

“Technology allows more latitude to ask a broader range of research questions, in a wider array of species,” says Bradfield. “That might really impact facility design. It’s entirely possible that we might see greater need for non-rodent species in multi-species facilities.

“I had a conversation with a large academic research institution using CRISPR on pigs and non-human primates,” says Bradfield. “It’s something they hadn’t even conceived of a few years ago, but now they’re building several new facilities, already doing that cutting-edge kind of work, already investing millions of dollars.”

Corey says a private research institution in the Northwest wants to expand its large animal facility to include pigs, dogs, and rabbits. “It’s a large new building, and the animal space is roughly 10 percent of it. That’s a fairly large expansion for the institution.”

That decision may not be for everyone.

“No one likes to deal with large animals anymore if they don’t have to,” says Joby Evans, PE, LEED AP, commissioning specialist and senior project engineer at Merrick & Company. “Waste removal is continuing to be a problem.” According to Evans, some municipalities will not accept the effluent directly from tissue digesters, due to high levels of biological oxygen demand (BOD). Facilities must install mixing tanks to collect sanitary wastewater and effluent water to reduce the BOD load.

Even with the opportunities that gene editing may provide, institutions may decide that they’d rather stick with mice, in part because the caging can act as the primary containment rather than the room itself, saving on both first cost and operational expense.

Tiffini Lovelace, an architect at EYP, agrees. “When determining the breadth of flexibility in vivaria, the line is cages vs. pens, in my opinion. The compliance issues alone going from rodents to large animals, and trying to design and maintain those facilities, would be an enormous financial undertaking. It would be difficult to transition a rodent holding room into a pen for large animals. In addition to different facility requirements, there are very different administrative, safety, and husbandry requirements.”

“It’s hard for me to see a widespread paradigm shift into multi-species facilities that are that broad,” she adds. “I’m not saying that it couldn’t be done, if you had the financial means available. It would be a scientist’s dream. But there aren’t enough institutions out there capable of, or wanting to, operate large animal facilities.”

If there were a demand for those kinds of cells, says Lovelace, perhaps a central facility for large animals could provide them.

The ARC

Memorial University’s 42,000-sf Animal Resource Center (the ARC) hits on many of these themes. The mid-sized regional university is planning to consolidate two buildings, dating from 1972 and 1995, into one space that is 15 percent smaller but much more efficient. The ground floor of the two-story multi-species facility will house Yucatan mini-swine, woodchucks (an infectious disease model for hepatitis), and zebra fish, as well as guinea pigs and rabbits as needed. In addition to drains, thimble connections will be configured for most of these first-floor spaces to allow for future flexibility. Also on the first floor will be cage wash, loading dock, staging/warehousing, a multi-purpose lab, post-mortem facilities, large-animal procedure and surgery spaces, ACL-2, and quarantine. Mice and rats will be housed on the second floor, along with small animal flex, procedure and surgical areas, behavior testing labs, an electrophysiology suite, and a room dedicated to a two-photon microscopy set-up.

The mechanical systems, which will be stored in a side house with its own foundation to isolate vibration, are a work of art in and of themselves. “It’s a very efficient and elegant design,” notes Jennifer Keyte, DVM, director of Animal Care Services at Memorial University. “We are very pleased to have the bulk of the mechanical services separated from the animal facility.”

In order to accommodate the needs of three faculties—Medicine, Pharmacy, and Science—many of the rooms in the new ARC will do double duty. The large-animal operating room will be outfitted with AV and moveable equipment in order to host resident training labs and classes. And the break room will have a moveable wall that can divide the space into a break room and a meeting/classroom.

While the animal and support spaces will all be new construction, a portion of the older Health Sciences Center adjacent to the new build will be renovated for the Animal Care Services’ administrative offices, and staff, student and faculty touch-down space. “Consolidation means that some faculty and students have to come from other parts of campus,” adds Keyte. “We want to make this a welcoming place, somewhere they want to spend time. It’s a real exercise in efficiency.”

Facility Operations

The ability to accurately monitor conditions in animal holding areas, as well as inside the cages themselves, is becoming an increasingly pressing issue. Digitizing facility management is critical for the care of the animals, as well as for satisfying reporting obligations. This year, it ranked third among project and program planning priorities in Tradeline’s survey, up from sixth in 2016 and seventh in 2015.

“Animals are uniquely vulnerable and dependent on the HVAC system functioning correctly, and when failures occur, the results tend to be catastrophic,” says Bradfield. “Having a mechanism in place to detect temperature excursions in a timely manner is essential for animal welfare and quality science. It ought to be a very high priority.”

Arriving at a solution can be complex, cautions Corey.

“It’s challenging for an equipment contractor to come up with a report that’s user-friendly,” he says. “They are using proprietary software. Owners need to provide a very deliberate definition of the report output they are looking for. Often it is not defined well enough.

“People are very concerned about the reporting they have to do for accreditation,” adds Corey. “Users have pointedly stated on the last three or four projects I’ve worked on that it’s very difficult to get the reports they need.”

“With staffing levels going down to control costs, they need more remote monitoring so they can respond quickly,” says Walsh. “Remote monitoring doesn’t replace the person on site; the alarm notifies both facilities people and animal staff.”

In the past, this monitoring was done by a separate system, says Walsh, but facility operators now want that monitoring integrated with their building controls.

The flip-side of building-based digital controls is a nascent re-examination of SOPs in favor of technological solutions.

“I would think, facility-wise, we’re going to start putting less of an emphasis on the building being the safety net for the containment,” says Lovelace. “There will be a move from putting all the bells and whistles into the building to providing proper SOPs and training.

“Faith in building technology is misplaced,” she says. “People think, ‘You put HEPA in BSL-3, and nothing bad can happen,’ but someone not washing their hands when they leave, or removing their gloves inappropriately, would bypass any bells and whistles.

“In my opinion, we are overdesigning BSL-3s,” says Lovelace. “The more complicated you make the building, the more things can go wrong.”

There is also a rethinking of long-held design norms.

“I have seen a trend in reducing airflows in BSL-3, finally,” says Lovelace. “I’m actually starting to see BSL-3s where the first point of design is 8 ACH. If you’re working safely in primary containment, with small quantities, the chances of something making it into the exhaust stream and out of the building are very small. A lot of things would have to go wrong.”

“Until recently, 10-15 ACH was considered gospel in animal facilities,” says Steve Niemi, DVM, director of the Office of Animal Resources at Harvard University, faculty of Arts & Sciences. “With individually ventilated cages (IVC), the rodents are often getting a lot more ACH than what’s going on in the room, and they’re doing just fine.

“The other allowance is for larger animals,” he says. “You can reduce the ACH as long as you remove waste often enough and make sure ammonia levels are monitored. It’s the outcome rather than an input that is the most important.”

Niemi is also exploring the cost/benefit of commonly accepted PPE practices.

“Conventionally when you walk into a rodent facility, you put on shoe covers, head cover, face mask, gloves, and gown,” he says. “But we’ve known for years that a micro-isolation cage is a reliable barrier to infection for the mice and allergens to the humans. Why are we putting all this stuff on if you’re just walking around?”

Niemi posits that street clothes are fine, if you are not engaging directly with the animals or with animal-contaminated material. That includes a supervisor following up on a request from a technician, vets doing a visual check on animals, mechanical support, regulators, and visitors on tours.

“Study after study has shown that it does not increases risk,” he says.

Despite the fact that these changes are saving $12,000 annually in reduced PPE purchases at Harvard’s Cambridge campus, they are slow to gain traction.

“Change is intimidating to people,” he says. “But we need to look at it with a fresh pair of eyes and see if what we are doing is necessary, what impact it has, what changes make sense.”

By Lisa Wesel