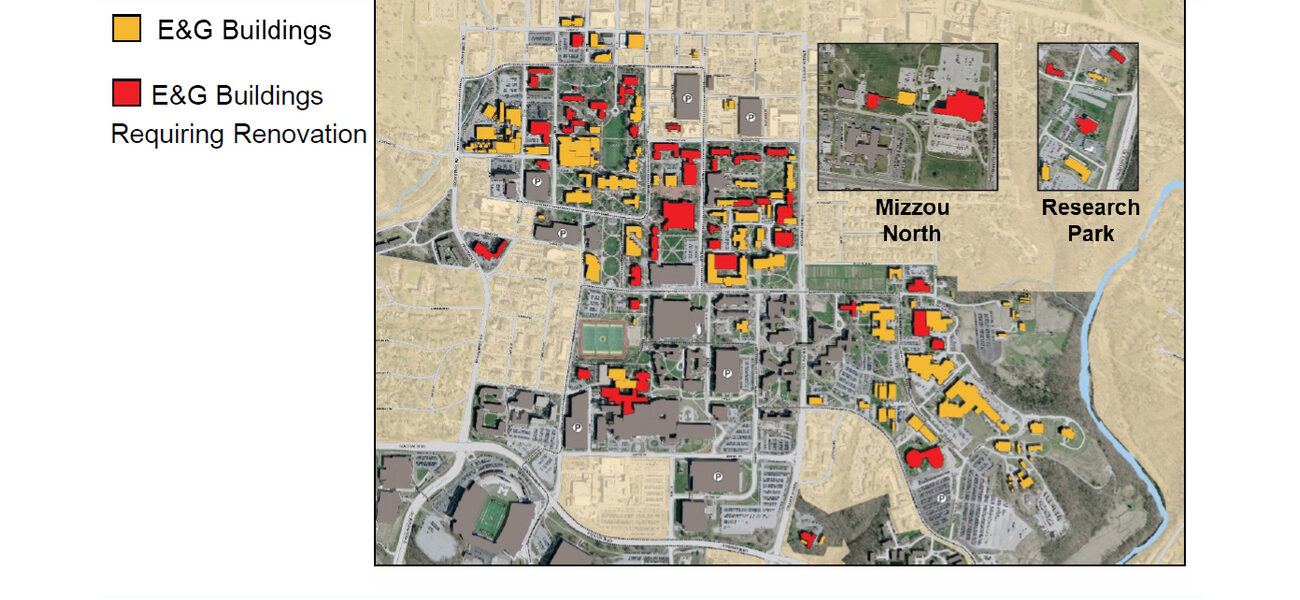

The University of Missouri (MU) will eliminate 750,000 sf of education and general facilities space by 2023 in order to reduce costs and improve overall space quality and utilization. The initiative will allow the university to save approximately $153 million in deferred maintenance, capital renewal, and plant adaption costs, as well as about $5 million in annual operating costs. It’s an ambitious undertaking, considering that the 1,200-acre main campus in Columbia, Mo., has 7 million sf of education and general facility space spread across 185 major buildings. To meet the 10 percent reduction goal over the next four years, the university will strategically demolish, divest, relocate, and rebuild a data-driven selection of aging or under-utilized buildings.

Currently, the university’s total backlog of needs for educational and general facilities is $844 million. Reducing the campus footprint will allow the university to invest recaptured operations dollars to create, support, and maintain existing and future high-performing buildings. It will also lessen the load on the MU power plant, allowing current capacity to be sufficient for a longer period of time.

“We are still trying to wrap our heads around how we can eliminate 750,000 sf by 2023 without any new square footage to accommodate the folks who will be coming out of the buildings we are planning to divest or demolish,” says Gerald Morgan, director of space planning and management at MU.

The university’s $14.4 million maintenance budget represents 0.53 percent of the current replacement cost of all campus education and general facilities. Professional facilities benchmarking organizations recommend that annual maintenance budgets should be at least 2 percent of replacement costs in order to provide for preventative maintenance versus strictly doing reactive maintenance, which is more expensive and disruptive for building occupants.

Identifying Needs

The university worked with several consulting firms to determine which facilities should be demolished, rebuilt, or remodeled to reduce square footage while improving overall quality.

“Sightlines is a benchmarking and facilities analysis consultant we work with,” says Morgan. “They compare data with peer institutions so we can see where we stand in relation to institutions of similar size, programming, and funding.”

Another consulting firm the university works with is Intelligent Systems and Engineering Services (ISES), an independent facility auditor that identifies specific building deficiencies and their associated corrective costs to create a Facility Condition Needs Index (FCNI). This index generates a number for each facility that estimates the replacement cost in terms of required maintenance.

“The Facility Condition Needs Index is our bible in facilities,” says Morgan. “It’s a list of all our buildings and the needs that have been identified for each of those buildings. For example, an FCNI number of 0.7 indicates the identified needs are equal to 70 percent of the current replacement value. We have established that if a building has 0.4 FCNI or greater, it needs a major renovation.”

In order to determine the first phase of space reduction and demolition, the university identified a list of about 15 high FCNI buildings that would not be cost-effective to renovate.

“For 750,000 sf, you can’t do that all at once. We knew it had to be broken into phases in order to reasonably manage this process, so, we started talking about those high FCNI buildings to decide what would be phase one. Maybe the location wasn’t great, or the space wasn’t conducive to being opened up or made flexible with a renovation. Our methodology was to identify buildings to move displaced people into. We looked for receiving buildings that have complementary uses to those of the displaced departments and also provide important adjacencies that could offer new collaboration opportunities. We also looked for receiving buildings that have a low FCNI, because we don’t want to move them from a high FCNI building into another high FCNI building,” says Morgan.

One aging space that was targeted for upgrade and remodeling was the MU cashier’s office, which had a 6,900-sf footprint in the main administrative building.

“The utilization of the space was very poor. So, we reimagined how we could compact that group and give them better space. We reduced them from 6,900 sf down to 3,100 sf and gave them a much nicer space with automatic-lifting workstations. We are now using this as a model to show other departments what can be done,” says Morgan.

New Strategies and Models

The university also began looking at new strategies and budget models that could help reduce square footage demands, including charging departments for their space.

“After this model was presented to our deans and department chairs, I started getting phone calls asking about space they would like to give back, and that was the goal. We knew they had space that wasn’t being well used, that they just sort of kept in case they expanded a program. Now they are looking to shed that space, which is very beneficial,” says Morgan.

Another proposed strategy is the central scheduling of classrooms by the registrar, as opposed to allowing classrooms to be departmentally controlled and scheduled.

“We had Paulien & Associates do a study in 2017. They found that our centrally scheduled classrooms had a utilization rate of around 70 to 75 percent, whereas departmentally controlled classrooms were down around 30 percent,” says Morgan.

Other alternatives include expanded teaching times, sharing of conference rooms, rethinking departmental libraries, evaluating graduate student space use, office sharing, and work-from-home options.

“There are certain individuals and functions that don’t need to be on campus and don’t need to have space, because that work can be done elsewhere,” says Morgan.

Communication and Transparency

An important aspect of the space utilization plan effort has been communicating goals, which include improving overall quality and utilization of space that allows for long-term sustainability and reduced costs, and provide updates about the process.

“This was a big deal, and we had a workshop with our master planner at Eastley + Partners to put together a communications plan. We put all of that information in a spreadsheet and send it out as a quarterly update, so everybody knows what is going on,” says Morgan.

Regular presentations are also organized for deans, faculty, staff, and other university stakeholders, in order to increase understanding and buy-in by keeping everyone up to speed on the process and taking everyone’s needs into account.

“It ultimately all comes down to furthering the academic mission of the university,” says Morgan. “But people are passionate about their space, so communication is absolutely critical. It’s important that you have empathy and listen to the people involved and that you’re as transparent as possible during the process.”

By Johnathon Allen

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

Sightlines

|

Benchmarking and Facilities Analysis

|

|

Intelligent Systems and Engineering Services

|

Facility Auditor

|

|

Paulien & Associates Inc.

|

Higher Education Planning

|