The University at Albany, State University of New York (UAlbany) has developed a rigorous new process for allocating space to improve utilization, decrease operating costs, and create more collaborative research environments capable of attracting high-quality researchers and students. The initiative was triggered in part by a growing influx of students and faculty and the creation of two new colleges—the College of Emergency Preparedness, Homeland Security and Cybersecurity; and the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences. The new space allocation and management process helps reduce the role politics plays in decision-making and better aligns facility use with university goals. The basis for the process is an understanding that campus space is a valuable limited resource that should be strategically deployed to achieve specific measurable goals, just like staffing or capital.

“We adhered to three guiding principles in this process,” says Benjamin Weaver, assistant vice provost and public service professor at UAlbany. “The first one is that space is a limited resource, much like funding or human resources. Second, no department owns space. Space is owned by the university. This means that we allocate it when it is needed and reallocate it when it is not being used efficiently. And third, space needs should be evaluated in the context of quantitative and functional considerations.”

The new process was prompted in part by the need to renovate the 1.8 million-sf “Academic Podium,” a single structure containing 15 original buildings. Designed by Edward Durrell Stone, the Podium has not seen significant renovation since its opening in 1964. This quantity of unrenovated legacy space at UAlbany magnifies the importance that scarce new construction must accomplish functions that existing space cannot.

“We needed to create these tools to address our space issues,” says Weaver. “In addition to building a new 225,000-gsf science facility, we are also renovating four buildings on our uptown campus. The university recently acquired the former Albany High School building and intends to renovate it to serve as the home for our College of Engineering and Applied Sciences. Even after this new construction and renovation, there will be 2.1 million sf of deferred maintenance remaining. Within this context, students are coming at a faster rate than we can provide space, and are requiring an expanded quantity of services. The university has to mine our existing space to get as much out of it as we can.”

Another contributing factor is that UAlbany is an R1 research university competing with much larger institutions with more robust grant portfolios. UAlbany has to do more with less, requiring a more strategic and precise use of resources, both spatial and capital. Among the university’s main goals are that research space should be both transdisciplinary and flexible, and that researchers be entrepreneurial in their endeavors. The university’s 10-year master plan was developed to ensure that each step of redevelopment is focused on the needs of the institution, not solely on the departments addressed in each phase.

“As part of the master plan, we mapped existing research disciplines to identify common research interests and topics of existing research excellence,” says Tony Alfieri, principal at Tony Alfieri, Architect. “Then we incorporated the university’s goals into a set of guiding principles that could inform the development of specific space planning metrics. Eventually the faculty committee members came to understand that this was very much not about taking space away from them, but about using limited resources to support them more effectively.”

Tools and Typologies

As part of this process, tools were devised for categorizing and managing the three main types of campus space—research space, instructional space, and office space—designating everything from how much space should be allocated down to the types of furniture and equipment in each type.

According to Errol Millington, director of Campus Planning, “We created a list of space typologies, and all of these types of spaces are now centrally supported by facilities. The goal is for conference rooms, class labs, meeting rooms, and faculty lounges to be allocated to academic departments based on criteria that can be measured and evaluated.”

A responsive three-step process for space allocation, measurement, and refinement was developed to ensure the university’s strategic goals remain aligned with actual space use. This necessitated creating and auditing a comprehensive inventory of existing campus spaces to assess occupancy and usage.

“As part of the process, the university sets an initial allocation for each type of space, then assesses that allocation after a quantity of time and fine-tunes it,” says Alfieri. “The initial allocation for research space is based on the type of research activity, not the discipline, modified by the number of people in the lab. That base allocation is further modified based on the degree to which that research advances the strategic interests of the institution. Of course, that includes both current and potential funding, but it’s not the only part.”

Labs and Research

Research space guidelines are activity-specific and divided into three categories: desktop research, benchtop research, and research that requires specialized equipment and instrumentation. Standards were established for each type of lab space, from office-based, to traditional wet and dry labs, to large bay spaces with high ceilings.

Once that framework was established, it was mapped back to the research disciplines on campus and the specific needs of research teams, including how many people are in each type of lab, how much write-up space is required, and what the needed lab components, procedure rooms, and support spaces are.

“We created diagrams to better communicate the functional potential of space quantities. These aren’t architectural solutions but they provide campus stakeholders a better understanding of the functions a space allocation can support,” says Alfieri.

One of the first test drives of the new process was applying it to UAlbany’s existing Life Sciences Research Building. Built in 2005, it offered the best opportunity to assess and realign research space to improve utilization.

The team looked at how the existing life sciences building could be restructured into a more modern flexible research facility by removing key walls, turning procedure activities into procedure rooms, and creating neighborhoods of transdisciplinary team clusters with open lab environments that increase density and collaboration. The purpose is to transform a modular and compartmentalized building given to a unitized allocation of space into a more dynamic research community with a more flexible use of space.

“UAlbany has had some of its greatest successes with researchers who have come to take part in the lifeblood of the university: The goal is to create a culture where teamwork and initiative is supported and that the energy created by that dynamic serves as a magnet for equally entrepreneurial researchers,” says Alfieri

Classrooms and Offices

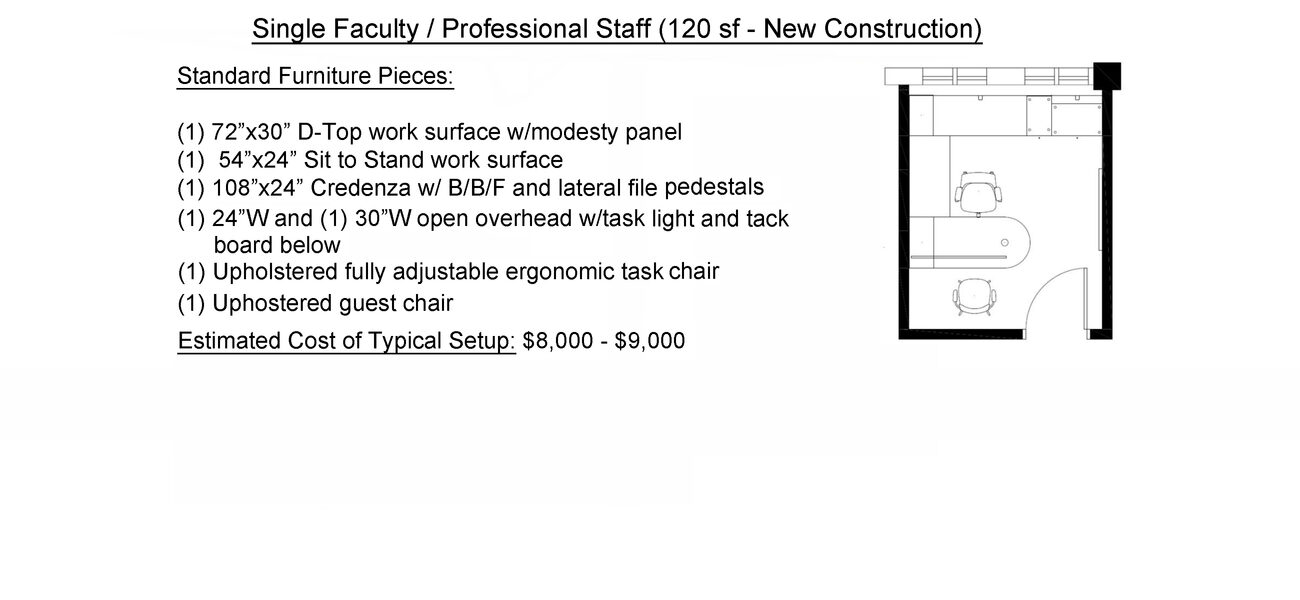

The guidelines provide a set of modular space allocations, as well as detailed furniture and equipment specs for every type of academic space. For example, a dean’s office is 240 sf with a private conference room, whereas a standard staff office is 120 sf, and a modular workstation for a graduate teaching assistant is 35 sf.

“We designed the furniture layout for every type of office space,” says Millington, “so when we go into a planning meeting, we have a common point of departure. It is a very equitable approach that allows participants to have flexibility without political jockeying. For that to happen it’s essential to have a full system in place that extends all the way from the big picture strategic plan down to what furniture goes into the offices.”

In addition to optimizing space allocation and removing faculty politics from the process, this modular approach is also useful for planning and budgeting. “Both the Office of Campus Planning and design consultants can use these furniture prototypes to establish more accurate furniture and equipment budgets. These analyses become more accurate the more experience we accumulate working with them,” says Millington.

There is a documented range of classroom sizes and types that match the constraints and limitations of the existing buildings. “The university worked closely with an internal innovative-learning technology working group looking at pedagogy in the development of these guidelines,” say Alfieri. “The standards allow classrooms to support faculty who predominantly want to lecture while allowing for a transition to spaces that support active learning.”

“When we first started managing the classrooms, they were almost 100 percent lecture-based, with 16 sf per seat,” says Millington. “As part of the new guidelines, we decided to transition to a 20-sf-per-seat arrangement with more emphasis on active learning, because we want to have participatory interaction in the classroom. There are whiteboards on the walls wherever there’s an opportunity, and all of the tables and chairs are on wheels.”

The space audit also revealed that the university had a surplus of space available during the day at their downtown campus, because it primarily hosts professional schools that teach classes in the evenings. By using the downtown spaces more effectively during the day, the university is better able to accommodate demand.

“We have been moving undergraduate courses downtown to complement the upper-division classes that are already scheduled there,” says Millington. “That policy is relieving some of the overload on the uptown campus. We now have software in the registrar’s office where a student can put in their work schedules and what classes they want to take, and it will generate five optimal schedules they can choose from.”

Outcomes and Scorecards

“With better space management across the university, there is less incentive to hoard space,” says Millington. “The transparency of the process has a lot of impact.” At every step, the point is to focus on the needs of the institution by supporting the greatest possible range of research needs of its constituent faculty.

“As space allocations change, core facilities are still there and available to the whole group,” says Millington. “But PIs are part of a team working around an activity. If space is transferred to a colleague that is collaborating on grants with you, it is less likely that you’ll think of it as someone taking something away from you.”

By Johnathon Allen

UAlbany’s Space Assessment and Allocation Tools can be found online here.