When Johnson County Community College asked them in 2015 to establish a space planning program, Janelle Vogler and Robyn Albano wondered where to start. Now they advise the college’s top decision-makers to optimize building utilization on campus. In launching a space planning organization from scratch, they point to several lessons they learned along the way: It’s vital to assign a point person to lead the effort; you need a team whose members commit to the institution’s interests above any one department; a successful organization will establish transparent processes for requests and decisions; and don’t be afraid to start data collection with a simple spreadsheet.

Established in 1969 in Overland Park, Kan., with original buildings opened in 1972, Johnson County Community College serves 18,500 students on a campus that has 1.5 million sf of facilities. It has been adding structures every few years, with two more—for fine arts and career technology education—under construction. Vogler, associate vice president for business services, and Albano, a space planner and interior designer, explain that over the decades, the campus grew without administrators having a detailed inventory of space use or an understanding of how well it served the school’s educational mission.

That’s where Vogler and Albano came in. College leaders tapped them to focus on space planning as part of a broader effort to develop a facilities master plan, completed in 2016. Among their goals:

- Use space planning benchmarks to allocate appropriate spaces to each academic department on campus, including locations and each program’s proximity to related programs.

- Identify the costs of space use, and assign costs associated with each program.

- Bring coherence to space use changes, including offices and departments that need to move to accommodate growth.

Now three years in, Vogler and Albano say that starting a successful space planning organization from scratch takes the right people, a clear process, and good data.

The Right People

Buildings are inanimate, but the people who work there create lives attached to them, says Vogler. Before the space planning organization started, faculty and staff were known to occupy unclaimed spaces as their own, for example. It is important for space planners to understand such cultural dynamics and work to reshape them if necessary. For Vogler and Albano, that means promoting an understanding that the space is there to benefit the college community, not any particular group.

“Departments are very, very protective of their space,” says Vogler. Once installed, she adds, “They felt that they owned it, and in some ways, they still do. We have really tried to change that culture to say that space belongs to the college and is there for the benefit of students and faculty and staff; it is not yours for life once you move in.”

It takes the right people to promote that culture and make a space planning organization a reality. The first step was designating Albano as the college’s space planner to lead the initiative and manage and collect space utilization and inventory data. Another essential duty is to serve as a liaison between the facilities department and the space committee.

With the college’s strategic priorities in mind, the space committee makes recommendations on space use, such as appropriate allocations or the need to relocate a department. It also fields space requests from groups on campus.

The space committee is not, however, a group designed to represent each department’s interests. In fact, the makeup of the committee—among the most important decisions for the space planning organization—includes people who embrace a best-for-the-organization attitude. “You need people who consistently wear the college hat,” says Vogler. “We even had a presentation where we all put on JCCC hats to remind everyone that you are not on this committee to represent your own division or your own department. You are here to represent what is best for the college, and that can be difficult.”

Vogler is a strong example. She worked for 19 years as an internal auditor, someone who, she says, “is neutral for all of the different divisions” at the school. She says this vantage point is crucial to making good decisions—and gives her perspective when fielding colleagues’ frequent hallway questions about the status of their offices.

Besides Albano and Vogler, others on the committee represent core functions involved in space planning, including the chief academic officer, and managers from the facilities department, information services, academic scheduling, and a liaison from the college’s leadership team. Though each brings functional expertise, Vogler says even more important for these members is an ability to take a college-wide view when examining specific space use questions.

Albano says they have kept the committee small by design, to avoid getting bogged down as they work to make recommendations to the administration.

A Clear Process

The space committee serves as a permanent steering committee for space utilization across campus, but it does not decide which professor gets what office or lab. That job falls to the college’s leadership team. The space committee occupies a middle ground:

- The leadership team is above, providing strategic direction for the college and setting priorities on space use based on the facilities master plan and other inputs.

- The space committee receives priorities from the leadership team, analyzes architectural and space planning data, and provides recommendations.

- Ad hoc space advisory committees convene for specific projects, such as moving a department, and work with members of the space committee to create recommendations.

Requests for new or changed spaces also go through the space committee. People fill out a space request form with information about their needs and suggestions for a location that would suit them. The space committee reviews the request, discusses the proposal with relevant parties, and evaluates alternatives before making a recommendation to the college leadership team to act on.

Vogler notes the importance of ensuring any program changes are supported by the requester’s department. This avoids misunderstandings, which the committee has learned through experience. “We got a request for an office that could be filled with treadmill desks and other kinds of healthy workplace alternatives for people to come use. That sounds like a great idea, so we were looking at that and trying to find an appropriate space. But what we didn’t know is that they didn’t have approval for that program for their own division,” says Vogler. “The funding for the treadmill desks had not been finalized yet.”

To help improve awareness, Vogler says members make presentations on campus to explain the college’s space planning organization, and how space requests work.

Good Data

While the right people and clear processes are essential to starting a space planning organization, nothing happens without good data, including data about: who sits where; the size and location of offices, labs, classrooms, and other spaces; the location of each assigned space and its relationship to assigned spaces nearby; what classrooms and labs are occupied, according to the college’s schedule; and future plans. The organization needs all of it to manage both existing inventory and future needs, to measure and improve how it uses space.

Albano says that information had been in different formats in different places at the college. The facilities department had data on mechanical areas in buildings. The academic schedule in an Ad Astra system provided views on when classrooms were busy. Staff directories had information on office occupants, but it required confirmation. There were floorplans for buildings. There was a list of college departments.

To get started, Albano says the team began simply, with an Excel spreadsheet to log data collected by walking around campus with a clipboard to take inventory—building, room number, organization or department name, square footage, and space use code. The codes come from the U.S. Department of Education Postsecondary Education Facilities Inventory and Classification Manual (FICM), known as “the red book” which provides guidelines for assessing space use for categories like classrooms, labs, and offices.

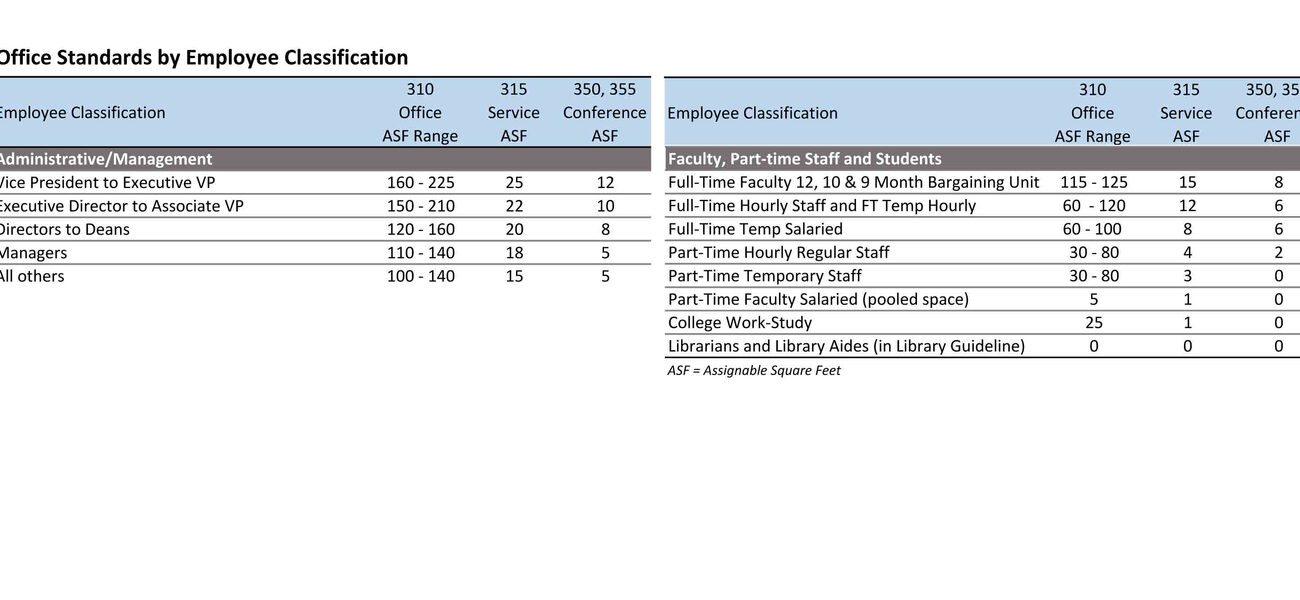

The college developed benchmarks for those categories with the help of a consultant who worked on the facilities master plan. Benchmarks show a full-time faculty member’s office could range from 115 to 125 sf, while part-time faculty members would expect to share a pooled space with 5 sf dedicated for each person.

These guidelines are valuable for space planners and provide a standard for faculty and staff expectations. But like any change in space management, the benchmarks are not without controversy. “We still get a lot of kickback, especially from faculty that have been at the college a long time who are used to having 160-sf and 180-sf offices. Then, with the new construction, their offices get bumped down to between 80 sf and 100 sf,” she says. “They are not always happy about it, but they know that it is in the interest of the college as a whole.”

While Albano and Vogler emphasize that the space planning organization needs to start somewhere with data collection—and Excel is a straightforward first step—they are looking into more sophisticated planning tools. For example, version control with Excel can be a challenge, and it does not help with forecasting or reporting as they would like.

The college plans to move its space planning to the Ad Astra scheduling system. It will help the space planning organization keep its inventory updated, but the team will have to customize the software to suit their needs.

By Michael S. Goldberg