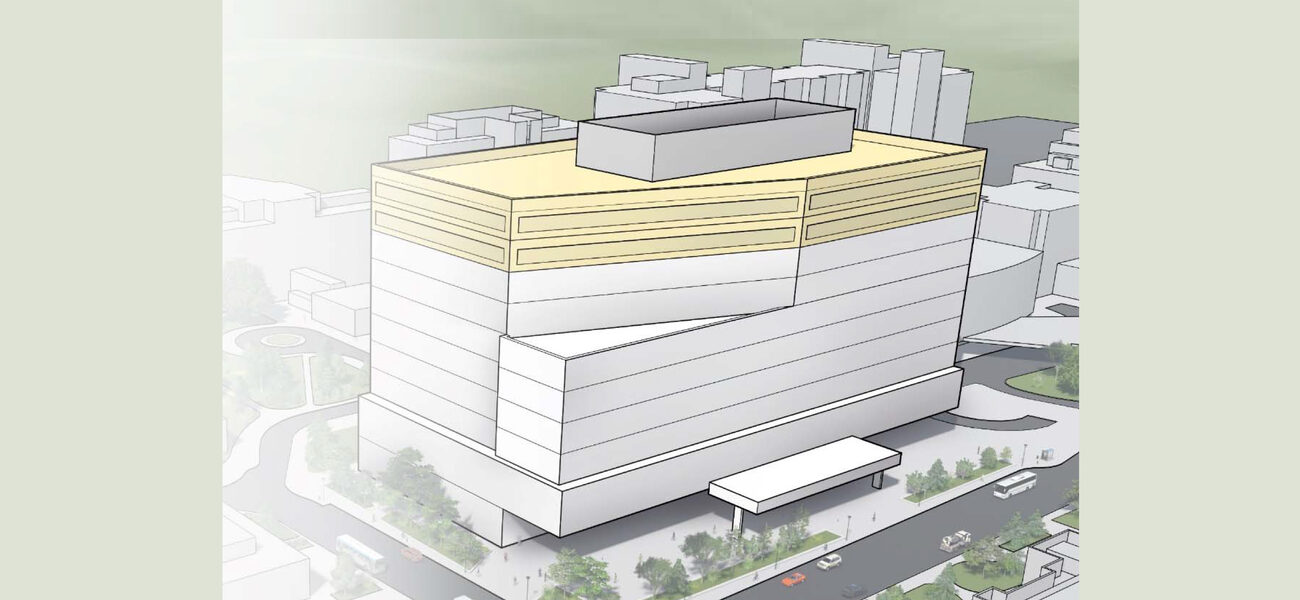

A public hospital in the Midwest was in the process of designing a new 12-story high-acuity ICU tower when the COVID-19 pandemic struck. They witnessed their colleagues in hospitals across the country struggling to accommodate the surge of patients who needed isolation units in facilities that were not designed for them, forcing them to shutter the revenue-generating general medicine practice in the rest of the hospital. So the Midwest hospital pivoted. They reassessed design options for the top two floors to serve as dedicated isolation/surge floors, when needed, without disrupting the operations in the rest of the building.

“It was an exercise in planning,” says Andrew Jones, project manager at Affiliated Engineers® (AEI). “They had the confines of the physical building already developed. They knew that they couldn’t go outside of the floorplate, so they had to develop a solution that would fit within that structure.”

The “small but meaningful” design changes, which Jones says many hospitals will likely consider in the future, can be applied in any pandemic that may arise, and may also be incorporated into existing facilities.

Small Spaces, Big Impacts

The key to fighting a pandemic is to break the chain of transmission based on the specific infectious disease, explains Fred Betz, Ph.D., LEED® AP BD+C, building performance consultant at AEI. With COVID, that means limiting exposure by air. With Ebola, it was all about direct patient contact and contaminated surfaces. The solutions embedded in the physical space can work for either one, but the best approach is to employ multiple solutions to create layers of protection, because you don’t know what the next pandemic will bring.

“Our focus for COVID really needs to be on what’s happening below the ceiling, in the spaces where people are, where they are infected and potentially can infect other folks,” says Betz.

In the case of the Midwest hospital, the floorplates are standardized so that every floor is laid out identically around 48 patient rooms. Included in the design options for the isolation floors were the addition of vestibules, or anterooms, to monitor patients from outside their rooms, minimizing exposure between patients and caregivers, and adding a layer of protection for both. If those patients had a bloodborne pathogen (Ebola, for example) instead of COVID-19, which is largely airborne, those anterooms could be used to store additional cleaning supplies and PPE. Flexible spaces for donning and doffing PPE were also designated on each floor.

These are not new solutions for high-acuity patients on an ICU floor, says Jones; they just needed to be incorporated into the standard layout on the floors that would be used as isolation units only some of the time.

Another design solution that adds a layer of protection is to assign a dedicated elevator that stops only on the designated isolation floors. This does not require a different kind of elevator, but a change in the way the elevator is digitally programmed.

Major Infrastructure Considerations

One of the larger items the owners of the Midwest hospital had to consider was a negative pressure exhaust system exclusively for the top two floors, which would give them the ability to evacuate the air from each floor and bring in fresh air.

Because this hospital was being designed as an ICU facility from the outset, it already had to adhere to a much more stringent code than one filled with standard patient care beds, says Betz. That means that designing those top floors for critical care required little additional electrical capacity in the headwall. However, treatment of COVID patients has typically called for increased consumption of medical air and oxygen. For this project, medical gas loads above normal ICU diversity were analyzed, and sensible investments in piping distribution were studied to ensure that the facility is prepared with the flexibility to increase the number of patients and level of need in the future.

Investment in increasing medical gas pipe sizes is typically minimal in regards to the overall budget of a new project. Installing additional or upsized piping in the future, however, and finding pathways and shafts can be a significant cost. Cost analysis should be performed to understand the impact of increasing pipe sizes for each system. “You want to be designing for flexibility,” says Betz. “Maybe you don’t necessarily put in those med gas lines on day one, but have a place where they can go in the future.”

Operational Solutions

The built environment—the infrastructure—goes only so far, cautions Betz. “We also have to think about human behaviors, and how we can modify those,” he says. “If you provide all of the investments in infrastructure available to you, all of those resources are meaningless the moment a bunch of folks sit around a table to have lunch. They take off their masks, and they start talking to each other, and you’ve just ruined all those other mitigation efforts, because you’re transmitting the disease now.”

Under normal circumstances, staff know that when they enter an airborne infectious isolation room with an infectious patient inside, they have to follow certain protocols.

“They’re super-cautious during that time, but once they leave that room and have disposed of their PPE, they can go back to their routine,” says Betz. “The problem with the current situation is that you’re never outside the quarantine zone, unless you’re outdoors. The whole building is effectively an isolation room.”

Retrofitting an Existing Hospital

The owners of the Midwest hospital were fortunate that they were still in the planning stage when the pandemic hit, because they had time to pause and rethink their design. Otherwise, they likely would find themselves scrambling when the next pandemic hits.

Their colleagues in existing facilities, who were hardest hit last year, still have options. The space and operational solutions—the anterooms, designated elevators, and PPE protocols—can be implemented with little disruption. With planning, anterooms can be carved out of an existing floorplate. And if an elevator is too old to reprogram, perhaps the surge space can be found in a wing on the first floor.

The bigger and more costly issues will be the HVAC and med gases. Installing more HVAC supply and return locations between spaces reduces cross-contamination, so room will need to be found on the roof for additional exhaust fans. The top floors of the building are the obvious location for surge space, because the negatively pressured isolation exhaust system will need to be ducted to the roof.

And increasing med gas capacity will require space in the walls for additional piping.

“We had to help retrofit a hospital—which I had helped design and finished in 2015—to handle COVID patients,” says Betz. “A lot of HVAC controls to manage airflows were value-engineered out in 2013 and 2014. That flexibility with HVAC controls—being able to direct airflows or shut things off or adjust pressurization—was missing in a lot of facilities. I don’t think, percentage-wise, having more robust controls was going to be all that much more expensive, but when you’re at the end of a project, $100 here, $100 there, multiplied 2,000 times in a large facility, adds up to a lot of money.

“And that’s specific to this pandemic,” he points out, “If that hospital had treated Ebola patients, none of those changes would have been necessary, as it’s a totally different set of circumstances. Hospital owners are essentially buying an insurance policy through technology that they may never use. Or they may use it a ton.”

“Headwall growth is also a real maybe,” says Betz. “Electrical supply and med gas is probably not coming from the roof, like HVAC does; it’s coming from somewhere else, and snaking that all the way through the hospital to get bigger pipes through might be too much of a challenge.”

There are temporary solutions to employ in a crisis, for example bringing in bottles of oxygen.

Looking to the Future

“The intent of this pivot in design is not specifically related just to COVID,” says Jones. “It’s really future-proofing these floors, understanding that infectious respiratory outbreaks are only going to continue in frequency in the future. Designers want to be mindful of flexible options for situations they might not know of yet.”

“You just don’t know,” adds Betz. “If you go through all the outbreaks we’ve had in the last 20 years, only one was really demanding of med gas. Ebola was a gigantic waste management issue, so you needed to have places to store contaminated materials before you shipped them off to get processed. For other diseases, you want to be able to clean surfaces really well, so you might want to have storage space for additional cleaning supplies. That’s where the flexible vestibule space is useful: If you need it to provide an air barrier, donning and doffing, store supplies—you don’t know what it’s going to be, but you want to make sure that you have something that you can work with.”

There are still a lot of unknowns. “Are those the three possibilities?” asks Betz. “You need to control the air, or the surfaces, or the waste? Controlling water would be another one. That’s mostly already written into codes, but that doesn’t mean some other bug coming in the future couldn’t have a massive outbreak that’s water-borne.”

“We often talk about designing a pandemic portion of a hospital, but ultimately in many cases, when it got priced, it was taken out because the hospital couldn’t afford it,” he says. “I think that will be a different conversation now.”

By Lisa Wesel