To achieve the most viable, successful workspaces, companies need to look closely at the factors that most directly influence their work culture instead of following the latest design trends, according to Kay Sargent, director of workplace strategies at Lend Lease. No single workplace design fits every company, and a workspace should fit the people using it, as well as the organizational goals.

Nowadays, everyone wants to be like Google, with its reputation as a hip, fun, state-of-the-art company. Google’s family atmosphere within its own self-contained, city-like space was designed to attract young high-tech workers and blur the lines between work life and personal life, so employees spend more time together. This drives innovation and pushes products into the market quickly, notes Sargent, but wouldn’t work for a pharmaceutical company, where products need to be vetted slowly and carefully, and failure is not an option.

“What Google does is what’s right for them, but most companies aren’t Google. The most important thing to do when designing workspaces is what’s right for your company. Know thyself.”

Benchmarking has validity, adds Sargent, but misses the mark on several counts: whether companies want to be doing what is being benchmarked, whether the workplace design is functional, whether the users like it, or whether your company is anything like those you are benchmarking. It’s important to examine what others are doing, but not rely solely on their experiences, she adds.

Collaboration is another popular concept, but studies show even the most highly collaborative people spend only 50 percent of their work time in this mode.

“We grossly misunderstand the concept of collaboration,” says Sargent. “Collaboration happens when people trust each other and bond. Then they will open up and say riskier things, and that’s where innovation and real collaboration happens. Throwing everyone into a big, open floor plate doesn’t mean they will collaborate.”

“If you are designing your space all about collaboration, you are totally missing the boat that the majority of the time people are doing heads-down, concentrative work.”

Assessing Corporate DNA

To get a clear picture of your company’s needs, says Sargent, look at “corporate DNA”—six factors that most influence a company’s workspace:

- The industry a business falls within

- Regional influences

- Demographics

- Corporate culture

- Organizational structure

- Individual work styles

"If any of these factors varies, your space solution is going to be altered,” she says.

Industries fall into the general categories of legal; corporate services; technology, advertising, media, and information (TAMI); healthcare; government; higher education; financial; and energy.

A game room may work in a high-tech or creative atmosphere, but not at a law firm, where they bill hourly. In corporate services, employees are often mobile, so smaller onsite spaces work for them. Healthcare work is typically individual work, stressful environments, long hours, with a focus on well-being. Government agencies are hierarchical, have an aging demographic, are meeting-intensive, and are spending taxpayers’ money so must be frugal. Higher education environments involve more individual work and office-based meetings; they are data-intensive and have an irregular schedule. Financial institutions tend to be more individual, concentrative work.

Industries vary in whether customers are coming into the workplace (legal, healthcare) or employees are going out into the field (sales, consultative), which also affects workspace needs and the ability to be mobile or work from home, says Sargent.

“The concept of working from home has absolutely nothing to do with personal preference and everything to do with what kind of a business you are. If you tell sales and consultative staff that they need to be in the office every day, your balance sheet is not going to be favorable. If you tell everybody who is a creative (worker) that they can work wherever they want to, your innovation is going to drop because coming together is when you synergize and move forward.

“The industry you are in should drive the decisions.”

Regional influences—whether urban, suburban, virtual, or rural—present different challenges. Traffic, density (lack of space), infrastructure, weather, and available work force are regional variations.

City workspaces have access to many amenities so probably don’t need to have onsite healthcare or food courts. Suburban settings might have limited public transportation, and organizations may want to create a campus setting with amenities, so employees don’t have to drive 20 minutes for lunch or to run errands.

Virtual companies can think about reducing corporate real estate, says Sargent. But they also need to invest heavily in ensuring that their technology works properly. These circumstances also can create a cultural erosion of the workforce, she adds.

“People work harder for the people they work with than the company they work for. If employees are never together, you are likely to have corporate culture erosion, and people don’t feel as connected. You have to make up for that, whether by bringing people in on a regular basis or having a strong intranet system.”

Workforce demographics affect design, because different generations have different work styles. Contrary to popular belief, baby boomers and Generation X are more apt to work from home, says Sargent. They have kids and aging parents, and have established themselves in the corporate system. Millennials (those born between 1980-2000) are more comfortable with the latest technology but also thrive on coming together, she says.

Gender affects work styles, too, notes Sargent. Women tend to communicate more and are consensus-oriented, while men are more dictatorial decision-makers. Women usually have more responsibility at home, which becomes an issue when they are in leadership roles. More female employees means companies need more flexibility—space-wise, in allowing work from home, in schedules—and/or have amenities onsite.

Demographics also include personality types, full-time/part-time schedules, and ethnicity. A mesh of ethnic groups is a big factor in today’s global economy. Companies may need to include prayer rooms in a workspace to accommodate employees. Even personal space needs vary between cultures, Sargent points out: In the United States, people want fairly large work areas, while in Asian countries, personal space is tight. And U.S. companies with sites overseas need to consider the local culture when creating those spaces, as well; telecommuting may not be a good option in countries where multiple generations live together in small spaces, for example.

“We are more connected globally today, so having a variety of ethnicities in your company raises sensitivity and awareness, which in turn helps companies learn the cultural nuances important to succeeding in business,” says Sargent. “It also helps them innovate, and think differently.”

Corporate culture can be formal, informal, casual, entrepreneurial, empowered or controlled. Is it important for employees to be in the office and be seen? Do managers need to directly monitor the work force, or is the atmosphere performance-based? Sales staff may never come to the office, or do so briefly and only need a small space.

The key to a successful off-site workforce is trust, notes Sargent. “If your company does not have that, a mobility program will be a disaster.”

The management structure of a company can be hierarchical, flat, web-based, like a hub with decisions spreading out from a central point, or completely decentralized.

“You should be able to look at your organizational chart and your space plan and notice a commonality between the two,” says Sargent. “Think about your organizational structure and your level of collaboration, and that ultimately should drive the floor plan. If you are not equating those two, you probably will have a process malfunction.”

A hierarchical environment requires a much different workspace than a flat structure where everyone is viewed as equal. At Zappos, the company’s CEO sits in the middle of the call center with the team. There are no walls, no individual offices. The same design wouldn’t work in the Pentagon, where the chain of command is ingrained in the culture—generals can’t sit next to privates, because information is compartmentalized, so some offices and layers or distinctions among spaces is required.

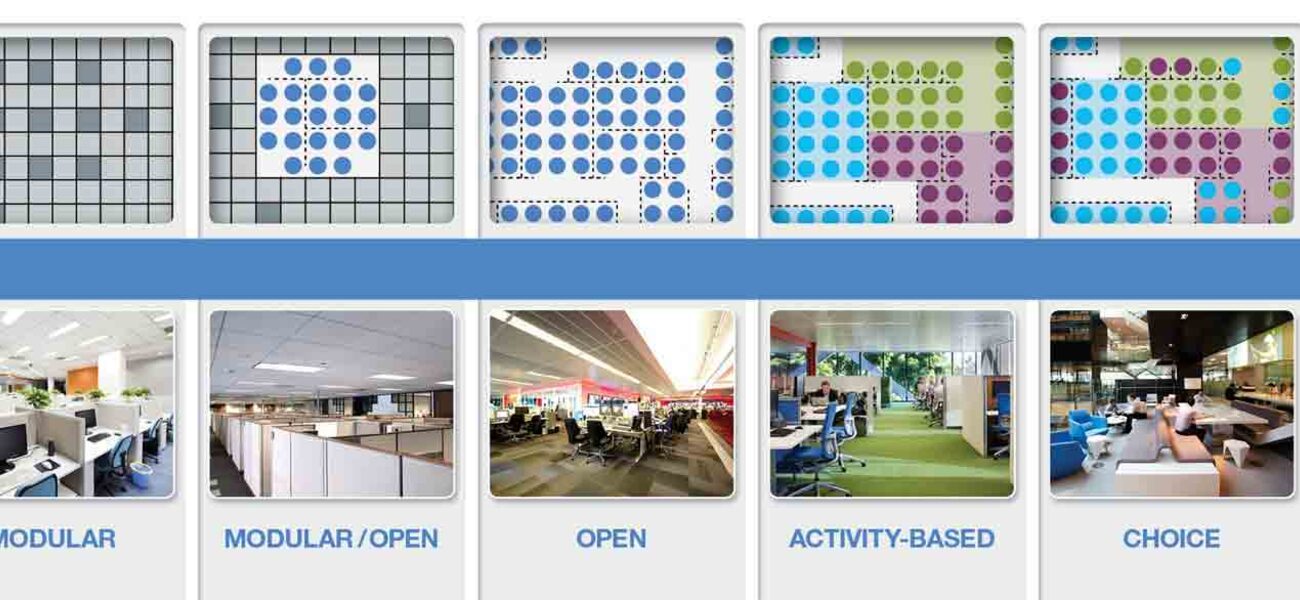

Work styles run the gamut from individually focused to meeting-intensive, collaborative, social, focused, or learning. These styles can overlap in one workplace, notes Sargent; companies may need to create a variety of smaller spaces within the floor plan, so people can choose.

“We’re starting to design spaces for more of a tribe mentality and creating ‘war rooms’ and ‘scrums’—working areas meant to be messy, with tables and moveable equipment where people can come together—like a working lab for knowledge workers. Another important part of collaboration is creating a visual learning environment, with displays and other means of visual information sharing.

“People tend to hatch ideas alone, but extrapolate those ideas in a group. That balance of space is often what’s missing today.”

Be Wary of Too Much Technology

While advances in technology have increased productivity by 500 percent in the last five years, according to one study, we are approaching the saturation point, says Sargent. Going forward, it’s anticipated that technology will only increase productivity by about 24 percent more.

“Technology has done amazing things, but in many environments, technology is now becoming a distraction,” says Sargent. Time spent responding to emails, trying to get technology to work, and otherwise managing technology can decrease productivity. Most people view emails seven to eight times before responding, and some people get thousands of emails daily, she adds.

“Technology is at a point where unless we can manage it better, it is going to bury us. The World Health Organization (WHO) says ‘techno-stress’ is going to be one of the biggest health issues of the future.”

Increasing reliance on technology also means people are less involved in deep, meaningful thought. All these factors are impacting design, says Sargent. Companies are creating quiet zones and technology-free zones, or policies that establish tech-free hours to allow people time to think, to contemplate, and to ideate.

Consider the People, and Be Patient

The most flexible thing in any environment is the people, and they also represent the most expensive part of any business, notes Sargent, as they are five to 10 times the cost of facilities. So it’s important to design what works best for them based on an organization’s DNA.

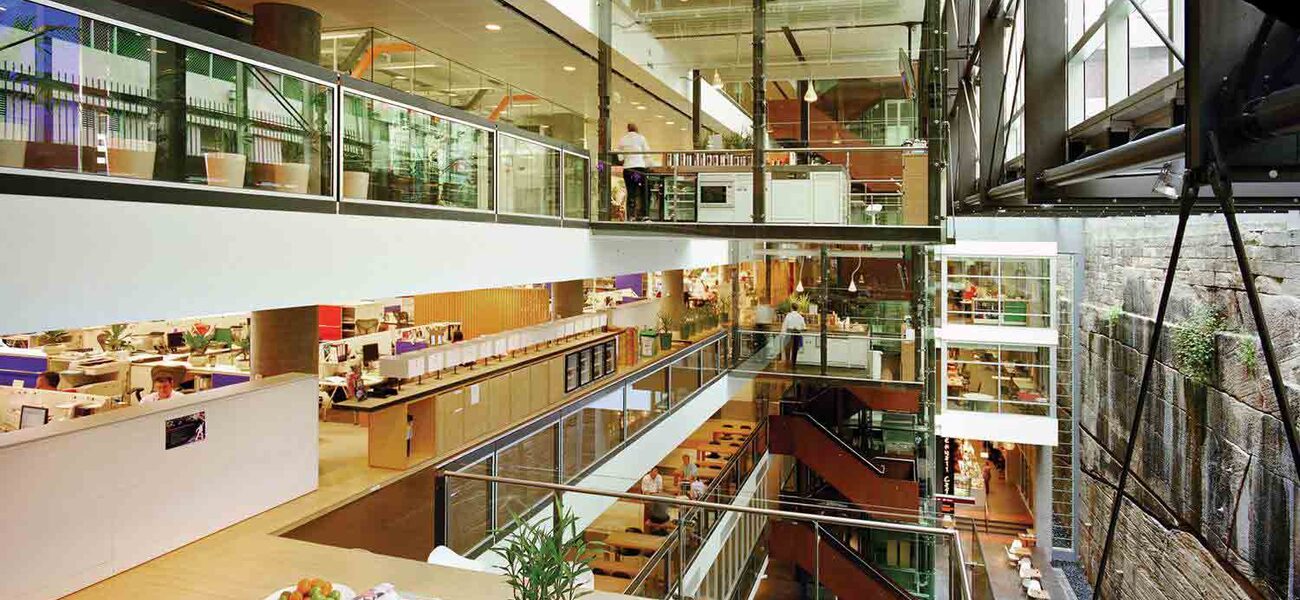

“We have always designed space as if people were potted plants and they go and sit in one spot all day. That is not healthy. That is not stimulating. That doesn’t drive creativity or collaboration. The workplace evolution we have gone through in the past several years is about giving people options.”

It’s also important to keep in mind that change is not without pain, adds Sargent. The General Services Administration (GSA)—the department of the U.S. government that serves as landlord for non-military government holdings—recently renovated its central office building in downtown Washington, D.C. The facility transitioned from six dedicated office areas to activity-based working, and employees don’t have assigned desks anymore but rather share workspaces. Some work is now done offsite.

This was a big cultural shift for an organization that previously had held a lot of meetings, and employees had their own offices, says Sargent. The transition proved tough for some people, and the GSA had to initiate change management processes, but it ended up being successful. In the end, GSA accommodated almost twice as many people in the facility, reduced its real estate, and encouraged people to work in a new manner.

“Change can be painful, but we are adaptable and I think we grossly underestimate how adaptable people can be. We also underestimate how much people will complain; people are whiny, but that doesn’t mean they can’t change.”

Changing a company’s culture is not easy, says Sargent, and redesigned space alone won’t change culture. But organizations should design space for their business goals and make sure those changes are supported by the entire organizational structure, including human resources, IT, and work processes.

“You need to be true to who you are, and if you want to shift the culture, approach it from all standpoints, including space. Space is part of a toolkit that will support a shift, but space alone won’t change culture. Think of who you are and where you want to go as an organization when designing work spaces.”

By Taitia Shelow

This report is based on a presentation Sargent made at Tradeline’s 2014 Space Strategies conference.