At the University of Minnesota, a renovation/construction project to add science space required detailed integration with the campus district plan, as well as preservation of historic features. The result was enhanced physical connectivity on campus, a careful blending of older and new construction, and improved energy performance.

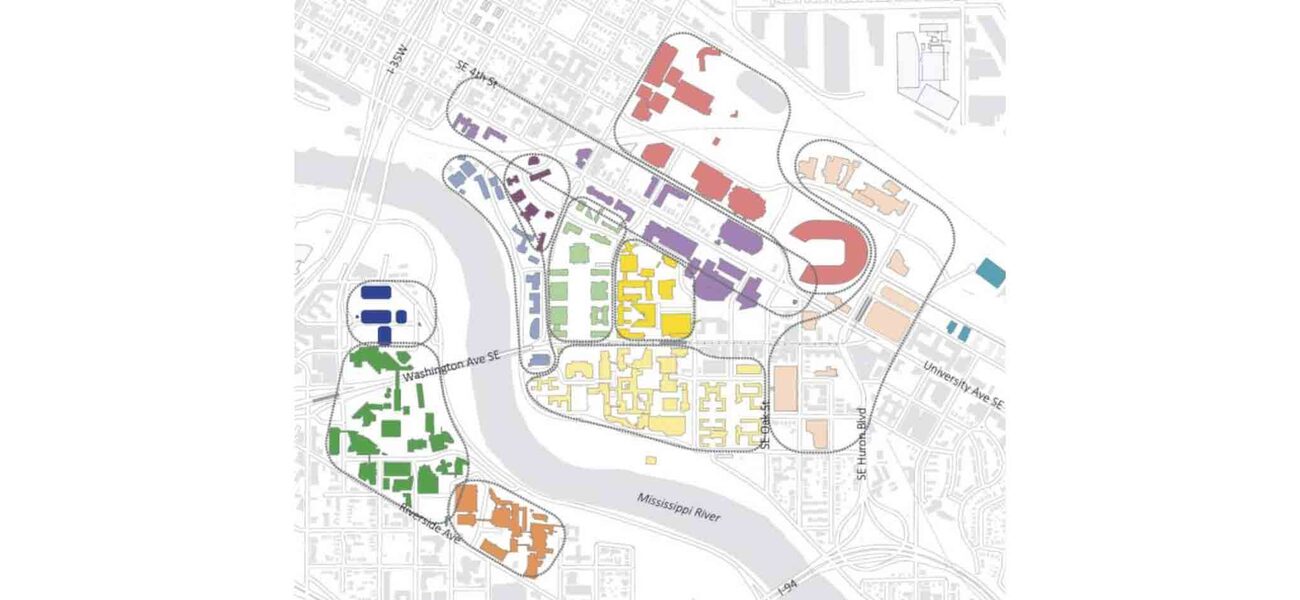

Tate Hall is one of 260 structures on the main Twin Cities campus, which is so large that planners have divided it into districts for planning purposes. The urban campus straddles the Mississippi River, and Tate, a horseshoe-shaped building first constructed in 1926, sat largely empty, as most of the physics department had recently moved to a new research building.

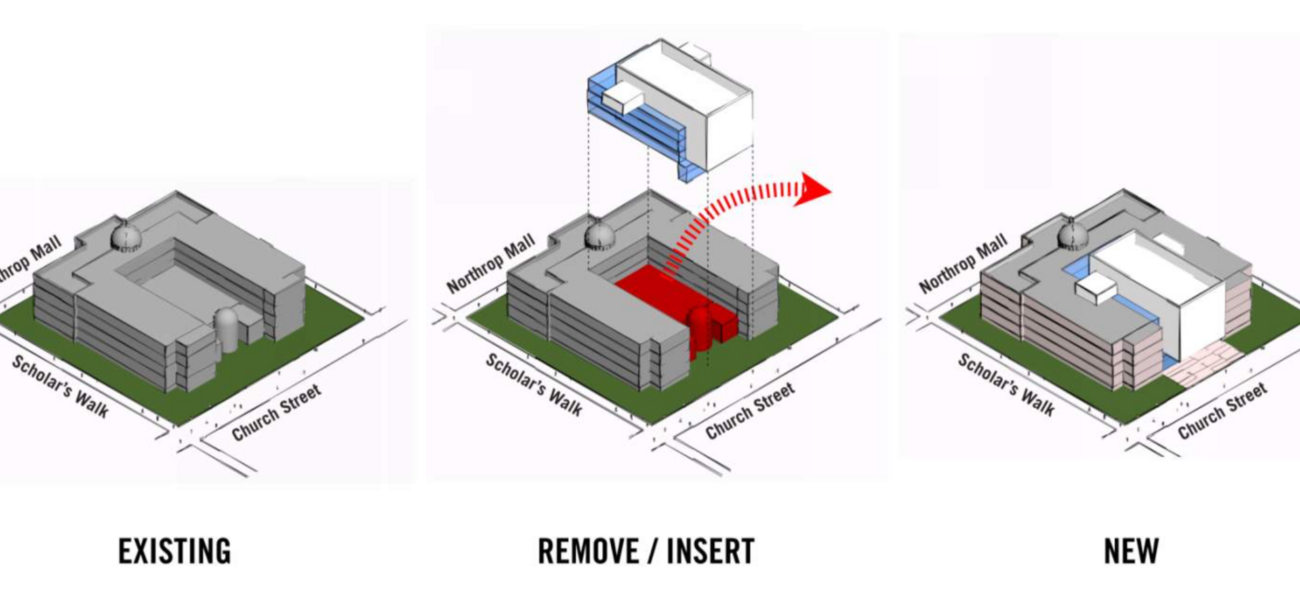

That created an opportunity for a renovation—a project that would ultimately include a new addition in the former courtyard to replace outdated classroom space. As part of an ongoing commitment to preservation of historic assets, the university’s planning process provided a proactive roadmap for solutions that would answer a host of sometimes conflicting requirements.

Districts, Costs, and Quality

The university’s master planning process describes attributes specific to each district. For instance, some districts are more historic, formal, and academic; others are urban-edge and connect to the neighborhoods that surround the campus. “Our design guidelines are asking that we transcend architectural style and think about more global ideas regarding scale, massing, or materiality of buildings within a district,” says Marc Partridge, design manager for capital projects and university architect.

The university then reviews each building every four or five years for its condition and fit. Partridge says the first stage of review is quantitative: “What is the cost of operating a certain building? What is the energy use of that building? Are there major code defects? Is it listed on a historic register?” The second phase is more subjective: Is the building well suited to today’s education methods? Does it create connections to its surrounding context? Is it beautiful, “challenged,” or a combination? Based on these assessments, planners classify each building as:

- Catch-up/Keep-up: Preserve assets, update mechanicals, invest in program improvements. About 80 percent of the main campus buildings are in this category.

- Sustain: Keep the building usable but avoid investing in program-related items.

- Do not invest: Maintain life safety but do not move departments or people in.

Tate Hall was chosen for renovation because of its historic value, because it is located on the historic Northrop Mall (an iconic open space for the campus), and because of the need for interdisciplinary research and teaching space in STEM fields.

Ken Sheehan, principal and head of the public market sector for Alliiance Architects, which was hired to do the design work, explains that they weren’t starting with a blank slate: “The university’s been really good about teeing projects up before they even bring design teams on. Much of the work of identifying the project for renovation had been prepared prior to hiring us to begin the pre-design.”

Sheehan and Partridge drew on three important planning tools for their work: the university campus and district plans; the goal of enhancing connectivity; and historical preservation guidelines.

Preserving Historic Value

Why preserve the historic features of a 1926 building? First, it’s the law. The University of Minnesota is required to work with the State Historical Preservation Office. “They are a great resource,” explains Partridge. “They are an advocate, to say the least, but that can create a healthy tension for us because their priority is to protect those buildings; our need is to put 21st century learning into these historic buildings.”

Second, historic preservation—creating a visual record of architecture in a place—is an important differentiator for today’s universities. “I think why that matters for us, why historicism matters, is that our campus is competing,” says Partridge. “We are competing with smaller campuses, with private colleges, and certainly with an online curriculum. What a campus brings is a physical presence. It is really important that we protect those assets that create a physical core, a place to be. Why would you come to a campus except for that social encounter with other people and the physical experience of a place?”

The Tate Hall project was envisioned as a home for earth sciences teaching and research, as well as theoretical physics and astronomy. This created a need for interdisciplinary spaces, but also provided the kind of coalition needed to fund the $92 million project, $72 million of which was for construction.

Sheehan’s team started by assessing the existing spaces, deciding to remove outdated teaching space to make way for the new construction in the center of the horseshoe. “We were already packing more program into the building than the current facility would accommodate, so we needed to optimize every square foot of the building,” he says.

Envelope and Mechanicals

To increase the accuracy of its building information model, the contractor and design team performed a laser scan of the entire space. This was particularly helpful in discovering undocumented building elements and making sure mechanical and structural components fabricated offsite would fit into the finished building. It also gave the team precise locations of historical features to ensure they would not be damaged in construction.

An important aspect of renovating Tate was to make it a usable building for this century—assessing the mechanical systems and envelope to improve energy efficiency wherever possible—while preserving the historic façade.

The challenges were many, including low floor-to-floor heights, solid masonry exterior walls devoid of insulation, and accessibility issues. Sheehan’s team reworked circulation patterns throughout the older building to improve connectivity and free up open spaces that had been blocked by, as he describes it, “a forest of columns.” While it might have been simpler to replace the windows on the older sections, the historic preservation office encouraged the project team to instead remove, restore, and reinstall the windows, adding storm windows on the interior for additional energy conservation.

The design team also added a vapor barrier and insulation in the most humidified portions of the building to prevent condensation on the exterior walls in the lab spaces and on the chilled beam systems. The solution wasn’t ideal—Sheehan says the team minimized the alterations to the exterior walls when possible. “We are concerned about altering the performance of these historic walls, as the freeze-thaw cycle can play havoc with the outer walls amid Minnesota’s climate extremes—but the university is aware of the possibility and is monitoring the building for signs of trouble.”

A Connective Center

Partridge cautions that the planning involved in staying ahead of building renovations is not a simple undertaking, and requires thinking in the context of the district’s identity, the campus’s goals, and the university’s mission. “Think about the appropriate interventions to a building in that context before you engage in design. Certain buildings may lend themselves to a new addition. Others may not.”

The Tate Hall addition, slotted neatly in between the two arms of the horseshoe, works to connect the building to its district, echoing but not replicating features of the older sections of the building, with large windows and an inviting first-floor atrium.

The result has been popular with the researchers who use Tate. Sheehan says, “When we talk to the researchers and faculty who are in the building, the thing that always comes forward is that they really appreciate the ability to perceive the new and the old in a way that is respectful and even celebrates the history of the building.

“It’s an excellent example of how you can fit very complicated and technical research and teaching space into a historic building with a significant number of limitations and constraints,” he adds. “It turned into an opportunity to provide a second life to the building.”

By Patricia Washburn