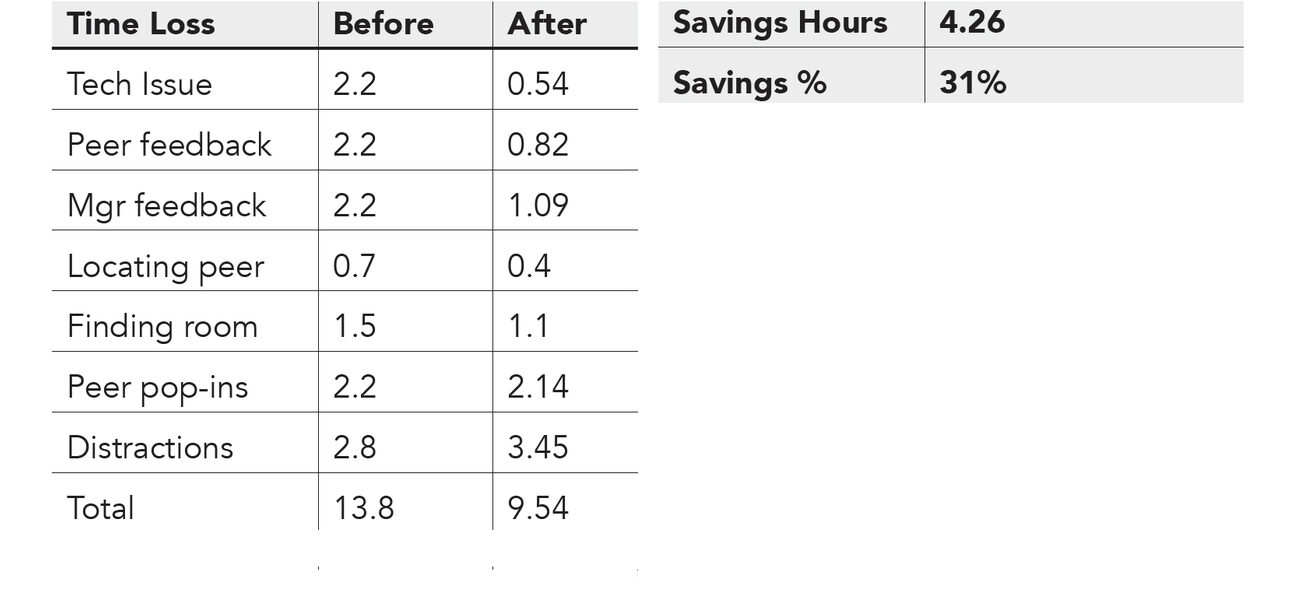

University of Michigan transformed Weiser Hall—a 1960s brick tower with floor after floor of double-loaded, concrete block corridors—into a dynamic and flexible “center of centers” that brings together international and interdisciplinary institutes and centers so they can share space, services, and ideas. The provost’s charge was to renovate the building to create the “academic workplace of the future.” With the help of brightspot strategy and Diamond Schmitt architects, the team accomplished that mission with a seven-step formula that yielded impressive results, including an average overall productivity savings of 4.26 hours per person per week, the equivalent of every unit being able to grow its staff by 10 percent at no cost.

This transformational project came at an opportune moment at the University. As one of the most unloved structures on campus the existing building was ripe for renewal. At the same time, the campus was moving to a shared services model, which meant that rather than every small unit having its own budget officer and its own events person, for example, these resources could be pooled and shared across units more efficiently. Rebooting the former Dennison Hall enabled the University to solve other problems, as well: The International Institute would be the anchor tenant, freeing up space elsewhere.

There also was campus-wide interest in moving away from planning projects by simply meeting with units, listening to their needs, adding them all up, and then building it. Instead, the University wanted to start planning more by function and less by specific department or school, in order to increase flexibility, sharing, and collaboration. In doing so, University of Michigan recognized that the University—and not its architect—had to be the primary change agent, so it enlisted brightspot to advise and support them in this process.

A Seven-Step Formula

Weiser Hall employed a comprehensive approach to innovative project delivery, full cycle from research to assess needs, through the post-occupancy evaluation required to measure success and fine-tune the building, policies, and operations.

Step 1. Conduct research: To understand the user’s needs, the team conducted interviews, focus groups, and an online survey, as well as analyzed event calendars and service transactions. From those findings, they created user personas to describe the motivations and behaviors of archetypal faculty, staff, and student users. They also uncovered interesting data to inform the planning. For instance, staff were more heads-down than faculty, on average spending 41 percent of their day working individually vs. 27 percent for faculty. The data also revealed priorities: Having time to think was ranked by 94 percent of respondents as the most important activity, but only 56 percent agreed that current space supported it. Culture, brand, and identity are key considerations, too, as dozens of different units would be coming together under one roof while still wanting a way to express their individual identity and work in their own way.

Step 2. Develop shared vision: Based on the research findings, the team then created a vision for the future with the advisory committee and the executive committee. A vision is a description of the ideal future state, with enough detail to make decisions about what would have to change to achieve it. Starting with a scenario planning workshop that identified the key decisions to be made and through several discussions and iterations, they created a vision for Weiser Hall to be a place that provides a sense of group identity as well as a globally engaged culture; offers a range of settings for different activities, including formal and informal; supports collaboration, focus work, study, and events; and fosters a culture of collaboration across disciplines and geographies, with seamless technology and support services, in a space that is magnetic, welcoming, and flexible.

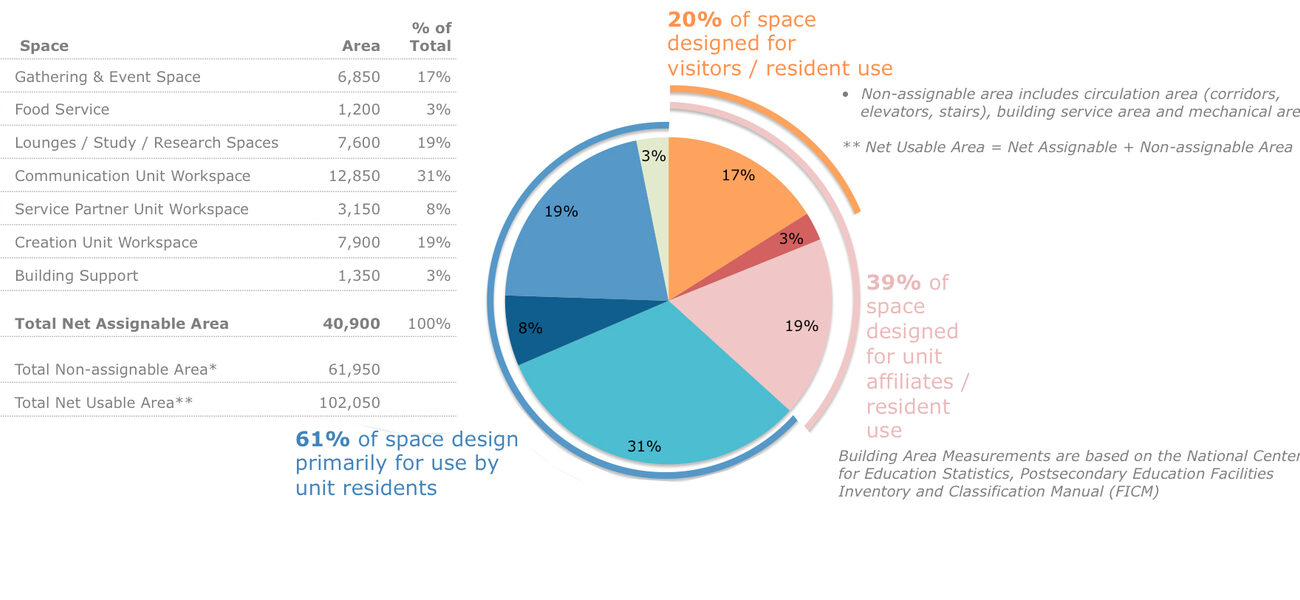

Step 3. Create a flexible program: Because the units occupying the building, their size, and the nature of their work were all subject to change, the team distilled units into different types and sizes and then used these factors to create a headcount-driven formula to allocate the approximately 100,000 sf of usable space. For types, they identified “creation units” as inward-facing and focused on creating ideas, often through deep thinking in an office and small groups at a whiteboard; “communication units” as outward-facing and focused on convening large groups of people and delivering programs in event spaces; and “service units” as those that provide support services to other units, for example information technology. Space is allocated using a formula based on the ratio of different occupants. For example, in a creation unit, 15 percent of the space goes to faculty because they comprise 15 percent of the occupants; 5 percent, managerial staff; 65 percent, staff; and 15 percent, grad students.

Step 4. Develop the design: The width of the building dictated that the floorplan be two rooms deep on either side of the double-loaded corridor, resulting in a horizontal layout of modular, flexible, four-room clusters. The same 120-sf room can accommodate a faculty office, three graduate students, or a five-person meeting space. The vertical layout fell seamlessly into place in a workshop with the advisory committee, as all the creation units sought the upper floors, the communication units the lower floors, and the service units the floors in the middle. One key design feature was adopted after site vists to several academic and corporate workplaces: double-height lounges on alternating floors that combine open and enclosed meeting space, as well as a shared kitchenette. A signature space for each unit—such as library, seminar room, or gallery—also emerged as a key design opportunity and a chance to express identity and culture.

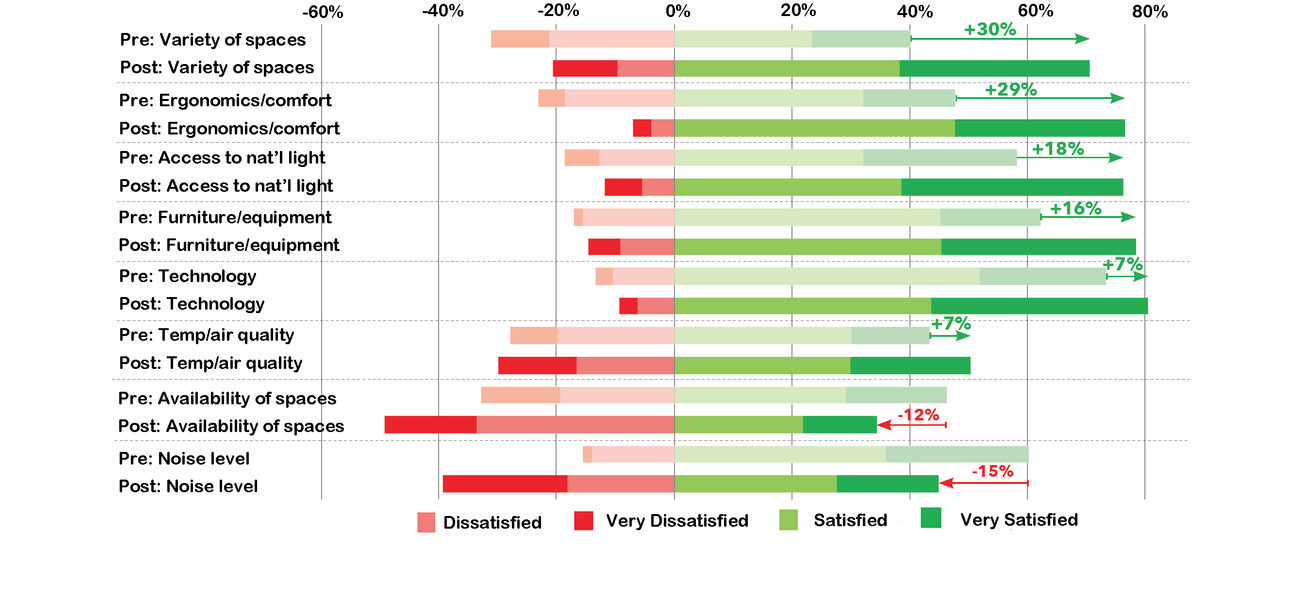

Step 5. Pilot the Concepts: To test the workplace concepts, the team capitalized on the opportunity to use one unit’s swing space as a pilot. They used the programming formula and prototype layouts as part of the process, and got feedback before and after. The pilot revealed that open workstations were a challenge for some people coming from enclosed offices; faculty enjoyed having student team space just outside their offices; and access to natural light was satisfactory, even though private offices in the four-room cluster were not all located on exterior walls. This proved to be an important change management tool, as well, because the swing space served as a great preview for future Weiser occupants to see the office size and layout, amount of glass and visibility, and typical grad student stations.

Step 6. Integrate Change Management: Because the new workplace represented a change in allocating, using, and sharing space and the technology and services within it, the team designed a change management program to inform, excite, and prepare people before they moved in. A change roadmap identified all of the different touchpoints with users, and a program to “train the trainer” equipped champions to then conduct retreats, so each group could learn about the building, meet neighbors, and set norms. A project website was created for information and updates, as well as a welcome guide to orient occupants to the spaces, services, technology, and units within the building.

Step 7. Measure the Results and Fine-Tune: Using the research data from the planning process as a baseline for comparison, the team conducted a post-occupancy study to measure the project’s performance and identify areas to fine-tune. A majority of occupants feel the building meets its goals, and 83 percent are satisfied with gathering spaces, 80 percent with technology, 78 percent with access to natural light, 77 percent with furniture, and 72 percent with access to colleagues. The picture is nuanced, though. For instance, satisfaction with ability to concentrate decreased by 11 percent compared to the spaces in the pre-renovated Dennison Hall, so the question becomes, is that an acceptable trade-off given that satisfaction with collaboration increased, and occupants experienced an average overall productivity savings of 4.26 hours per person per week? As a result of the findings, the University may adjust some unit locations to optimize adjacencies, and has undertaken additional work to clarify and communicate norms, particularly for students who, due to the project’s success, can be found working in every nook and cranny of the building.

How to Get Started

When applying this formula to fuel workplace innovation on campus, pay special attention to the project structure and setup, stay flexible throughout, and integrate change management into your thinking.

To set up the project for success, create an advisory committee to represent different units, an operational committee to think through services and operations, and an executive committee to make decisions. Also, designate a “faculty shepherd” for communications to ensure faculty are hearing from a colleague when it’s time to organize a workshop for input or gather feedback.

To stay flexible, don’t think of deliverables like the space program as static; instead, create dynamic ones that change as the planning progresses, within pre-established boundaries or constraints. Also look for opportunities to make things modular—the more rooms you have of the same size, the easier it will be to change the function or the occupant down the road.

To integrate change management into the process, set the goal to have everyone informed, excited, and prepared about the transition, and then follow through by involving people throughout the process with a project website, regular meetings, tours, a welcome guide, and move-in celebration. Use swing space strategically by setting up a pilot to test the new space strategy, which provides the opportunity to make mistakes and then make refinements before you cut the ribbon on your new facility.

By Elliot Felix and Susan Monroe

Elliot Felix is founder and CEO of brightspot strategy; Susan Monroe is capital projects manager of University of Michigan.

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

Brightspot Strategy

|

Change Management

|

|

Diamond Schmitt Architects

|

Architect

|