Science programs face the same pressures everywhere—a need for tech-enabled classrooms, demand for doing more with less space, emphasis on flexible research space, and practical considerations pushing departments to share resources and work together. At tiny Ursinus College in Pennsylvania, a new science building is meeting these challenges by physically connecting departments and expanding non-program spaces.

The college had two science buildings next door to one another, with 1930s Pfahler Hall housing chemistry, physics/astronomy, math/computer science, and environmental studies; and 1970s-era Thomas Hall providing a home for biology and psychology. The new building, Innovation and Discovery Center (IDC), sits in the space between the two, with physical links into it from both older buildings.

“Architecturally it was quite a challenge to come up with a design that would blend the buildings together,” explains Victor Tortorelli, a chaired professor of chemistry at Ursinus who served as point person for programming, design, and construction of the IDC. “For instance, the floor-to-ceiling height in Pfahler was quite generous, and the first floors of Thomas and Pfahler were about 6 inches apart.”

The physical connections were a major priority, though construction was a challenge because classes continued in both Pfahler and Thomas during the building process.

“Collaboration was going to be critical, and we wanted a facility that would encourage interactions purposefully,” says Tortorelli. “That is, we wanted to have lots of non-program spaces so we could have faculty-faculty, faculty-student, and student-student interactions. There was also a critical need, especially in our biology department, to increase the square footage devoted to research.”

Common Areas for Casual Conversations

At the north entrance to the IDC is a large common area with comfortable seating and room for poster sessions and presentations. “We like to think of it as the family room for the college,” says Tortorelli. “The college did not want this building to be strictly a science building. We wanted to attract students and faculty from all disciplines into the building.”

True to this vision, he says, there are students using the common spaces at nearly every hour the building is open. “These are spaces that are very heavily used by students. You will see students and faculty interacting in these areas, as well,” says Tortorelli. “Students are here when I get in early, there are students here when I work late. There’s an opportunity for students passing through to plop down and get some work done.”

Up on the second and third floors, informal student spaces include walls that are floor-to-ceiling whiteboard. “Students love the non-program spaces, comfortable chairs, whiteboards everywhere. Students will stand up on these nice chairs that we spent a lot of money on, and write way up on the top of the whiteboard and then take a picture with their phone,” he says.

“The first two weeks we were open, students would come in and draw pictures. Now they’re full of equations and lists,” he says approvingly.

Who Are the Researchers in Your Neighborhood?

The building’s design also sought to foster collaboration by creating academic “neighborhoods” where people doing related work might easily interact. “We group people together based on similarities in the kinds of methods they’re using,” explains Tortorelli.

The second floor is a biology neighborhood, anchored by a biochemistry teaching lab. A nearby research lab houses four faculty members—a biochemist, a physiologist, and two researchers from the health and exercise physiology department. The grouping is both practical—shared resources and support spaces can support all of them—and flexible, with utilities fed from above and movable benches to accommodate changes in research, staffing, or technology.

A histology support lab is carefully located so it can be reached easily from the IDC laboratories, but also from nearby research space in Thomas Hall next door. Down the hall, a cell culture support lab is equally accessible.

The third floor is a neuroscience neighborhood, with connections to the psychology department in Thomas, plus a teaching laboratory, common research equipment such as refrigerators, freezers, and a shared microscope space that is accessible from both the lab and the common hallway.

Interdisciplinary Effect

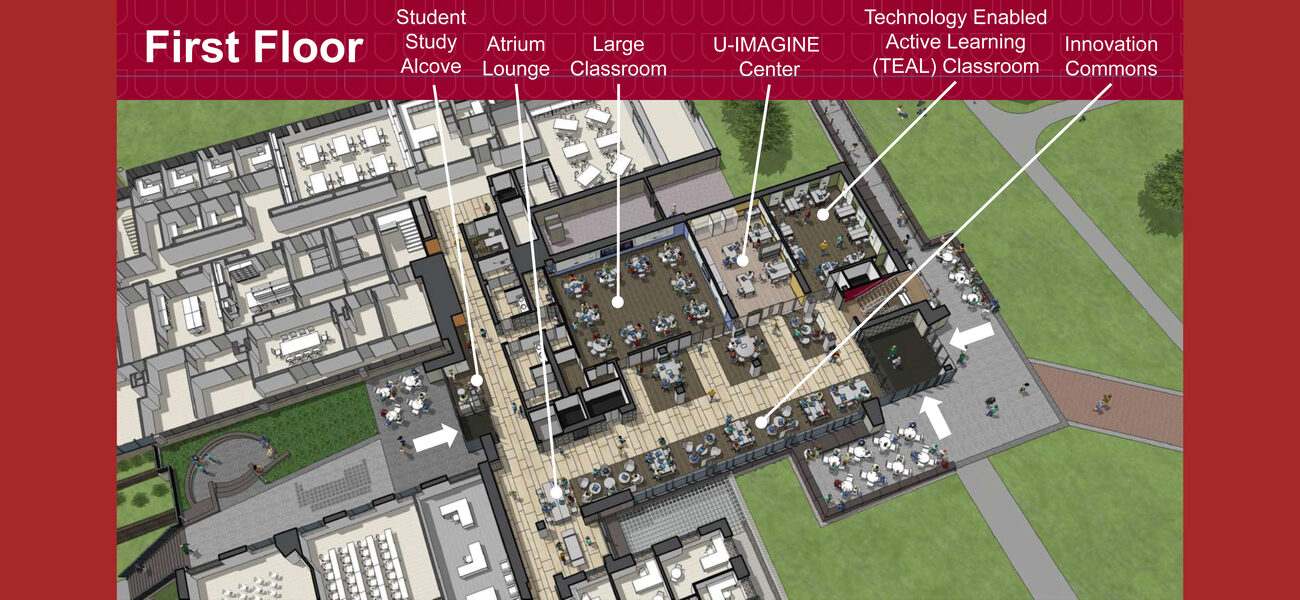

Ursinus moved two of its three interdisciplinary centers into the new space, and certain classrooms in the IDC also welcome classes from outside the science fields. The TEAL (Technology-Enabled Active Learning) classroom incorporates up-to-date pedagogical tools such as monitors on the walls and group seating, with teams able to share their work electronically with a larger class.

“It’s a great space if you’re teaching a project-based course,” says Tortorelli, crediting the room’s success to thorough planning and “very good consultants.” Science classes take place there, but so do classes in anthropology, economics, and other fields. Flexible furniture solutions are also available in the “large classroom,” which at Ursinus is much smaller than big classrooms elsewhere—only 56 students.

On the first floor is the U-Imagine Center for Integrative and Entrepreneurial Studies. More than a maker space, this center seeks “to provide any student from any major the resources necessary to develop an idea into a product or service that creates value by meeting a social or market need,” says Tortorelli. An entrepreneur-in-residence provides guidance and workshops, and the center encourages all students to learn from visiting lecturers or take advantage of the opportunity to develop ideas. In the summer, the center matches students with local businesses to collaborate and learn about social media and marketing.

On the second floor, in with the shared lab resources and biology neighborhood, is the Parlee Center for Science and the Common Good. Its mission is to study the connections between science and other ways of understanding—ethics, the arts, and politics, for example. The Parlee team recently carried out a yearlong study centering on concussions in sports, with the goal of making a science topic accessible through a variety of disciplines, with experts on hand not just for students, but for the whole community. Because the center’s activities take place mostly in the afternoons and evenings, the space also serves as an active-learning classroom.

Thorough Planning

Tortorelli credits the planning that Ursinus’ team did with the success of the new space. The construction took 18 months and came in under budget.

The genesis of the building came 10 years earlier, when Ursinus’s science departments embarked on a strategic vision process and identified three key needs that the new building ultimately fulfilled: collaboration space, research space, and integration with existing program spaces.

So how do you pull off a pass-through building in a tight space and provide for the institution’s greatest needs? “It was key to make sure you had all the right people in the room. You can never do enough of engaging the correct people,” says Tortorelli. “Really ask the right questions so you can get the space right the first time and not have to go through change orders and early renovations.”

By Patricia Washburn