Faculty in higher education often spend less than 20 percent of their workday at their assigned desks, so why do they still have them? It is a question that academic administrators are asking, as they look for ways to provide building occupants with the spaces they need to do their work and the autonomy to select the right space for the right task, all within an increasingly constrained campus footprint. Corporate offices have been making the transition to unassigned seating for years now, and despite trepidation, there are signs that academia may be following suit: In a recent survey of 88 U.S. colleges and universities (conducted by the Society for College and University Planning and brightspot, a Buro Happold company), about 62 percent of respondents said they are pursuing more flexible or unassigned workspaces for administrative staff, and 54 percent are planning to do so for academic work facilities, as well.

Faculty arguments against free-addressing—the need for privacy and a quiet place to do heads-down work, to be accessible to students, and the notion that academic endeavors are somehow different than corporate pursuits—can all be addressed by providing the right variety of workspaces to accommodate the constantly evolving way that people work, says Margaret Serrato, workplace strategist at AreaLogic Workplace Strategy.

“Today, most professionals, including faculty members, work much the same way,” she says. “Whether a professor, lawyer, accountant, or architect, when we are at work, we are usually either working alone at our computer or we’re in a meeting. The content of our work may differ, but the process of work is very similar.”

Faculty say they need a space of their own so their students can find them, but there are so many ways that students and faculty communicate—via email, texting, messaging—that they often schedule meetings outside of office hours, anyway.

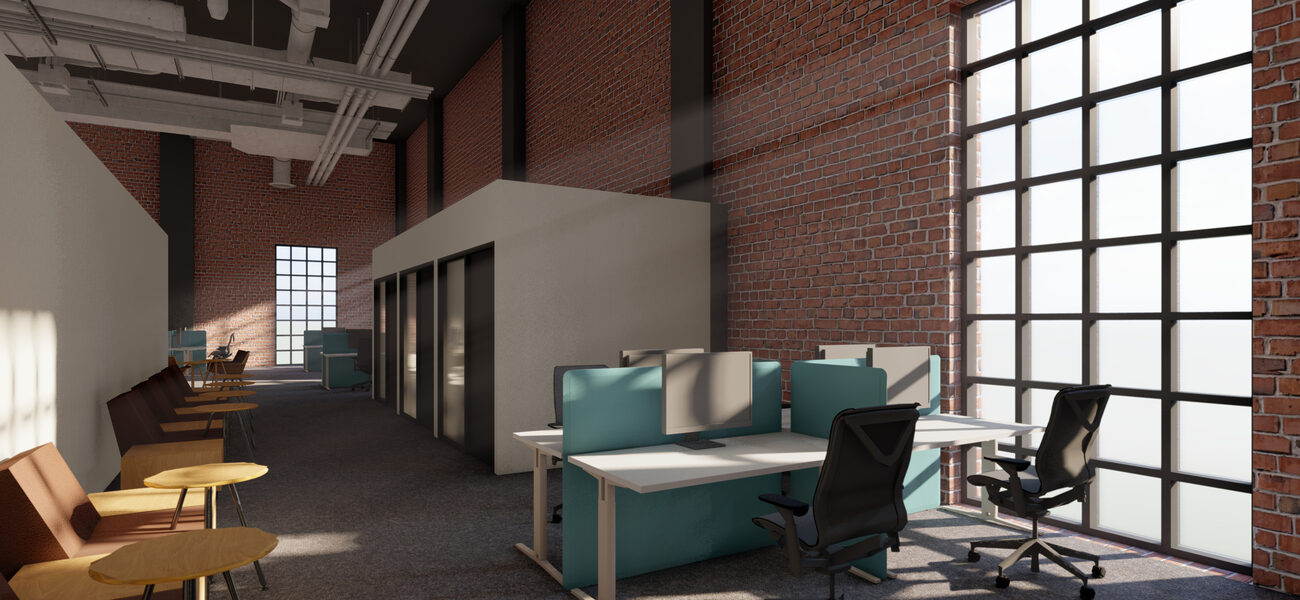

Faculty also say they need privacy. “It’s true that faculty need privacy for focused work or for meeting with students,” says Serrato, “but when they say they need a dedicated space of their own, I suggest that, rather than owning that space, there is a different way to provide access to many types of private spaces while still meeting other goals of space utilization.” For example, Serrato recommends an activity-based workplace, which provides intentionally located layers of a variety of unassigned spaces that people may select to fit the task at hand.

“People are smart and adaptable about how, when, and where to work,” she says. “If we give them the tools they need to work, including the ability to reserve a well-furnished private office when they need it, then much of the pushback about shifting to a free-address workplace evaporates.”

Wake Forest

Wake Forest School of Medicine is slowly, incrementally, inching away from allocating space based on rank and toward the concept of activity-based workspaces. Three or four years ago, the campus did away with faculty having more than one assigned office, even when they have dual appointments. Now they have one assigned space—either an enclosed or an open workstation—in the department of their choosing, and their seat in the other department is a hoteling space.

This policy was cemented in the iQ Healthtech Lab, which is not anyone’s home base. It is a space where researchers from the School of Medicine can partner with researchers in private industry with a focus on finding solutions to improve health, in a co-working environment where all of the seating is unassigned.

“It is a place for problem-solving, collaboration, and idea generation in the healthtech industry,” says Jason Kaplan, associate vice president of the School of Medicine. “It helped in the genesis of it that we had industry as a partner. Companies can be more forward-thinking about space utilization.”

The iQ Healthtech Lab is located on several floors that offer spaces for events, meetings, and both individual and team work. Adjacent to those spaces are dedicated innovation suites where entities can rent small offices by the month.

Kaplan is hoping that the iQ Healthtech Lab will serve as a model of unassigned workspaces.

“We are on a path toward work activities—you will have the space you need to perform the work you do,” says Kaplan. “We let departments allocate their own space in their own footprint—if you all are assigned by rank, you’ll run out of space quickly. And they will. But they aren’t there yet.”

The hard part, of course, will be to get buy-in from faculty.

“We’ve learned a lot during the pandemic,” says Kaplan. “A lot of our faculty were working hybrid already—working from home, traveling, doing analysis that they can do in any location. There was low utilization of offices even pre-pandemic, but they would say otherwise.”

The medical school has initiated the use of occupancy sensors to bridge the gap between perception and reality. When anyone asks for additional space, they are requested to install sensors to show how much they actually use the space they already have.

“We received a request from one of our departments for additional space,” says Kaplan. “They declined to participate in the sensors, and the space request went away. For some, it’s too early to go there. I think, using this data, we will change how we assign space, but it’s a huge behavioral shift.”

The medical school recently released an RFP for programming a neurosciences research building, scheduled for completion in four or five years, which could be the school’s first foray into activity-based facilities as a primary workspace. It’s a graduate- and doctoral-level teaching facility with a small cohort of faculty that spend most their time in the lab.

The Power of a Pilot

The primary reason a facility asset manager would consider free-addressing is to improve space utilization, says Serrato. The Harvard Graduate School of Education installed motion detectors under the seats of 260-300 faculty and learned that they used their office about 19 percent of time, which is fewer than eight hours per week. But Serrato cautions against using data like this simply to take space way from people while still telling them where and how to work—often to create “collaboration space”—which has historically been the case and has historically failed.

“You don’t need to manage people that closely. If you do, you’re not hiring the right people, or you have this thought that it’s 1960, or you’re a lieutenant and you’re running a platoon. Don’t try and control people’s lives. We make choices everywhere we go, but once you cross that threshold into work all of a sudden, you’re a controllable item. People don’t like it.”

What people need most to be happy and effective is autonomy. “Innovation is not just about collaboration, it’s about supporting individual work and giving people the choice to find the kind of space that works for them,” she says.

According to research conducted by Herman Miller for Lendlease, the number one driver of an occupant’s ability to adapt quickly to a new workplace environment is giving them control and choice. “You can put in fancy furniture, the best coffee machine, a rock-climbing wall, and beanbag chairs, but what people seem to care about most is choice, because that gives them control over their environment,” explains Serrato. “It will be successful as long as you have a nice blend of open and closed individual, group, and community spaces, layered in a certain way. Choice transcends everything.

“I tell people at university settings, ‘Don’t be afraid of change,’” she says. “It’s not that hard. Create a pilot, but it can’t be a pilot where everyone still has their office someplace else. The pilot has to become their primary workspace.”

Serrato is working with a Southern liberal arts college whose president is concerned about how much space on campus is underutilized. “She told me, ‘I walk around the buildings during the week, and I can hear my own echo.’” But her faculty is resistant to changing the status quo of assigned offices for every faculty member. Instead of forcing unassigned seating on them, she is planning to let them come to appreciate it on their own.

The college is creating a two-story addition to an existing building that will be designed as a progressive workplace—free address, activity-based space that is carefully organized based on an algorithm that Serrato created: Take the total number of people who will use the space, then assume a maximum utilization of 50 percent. If more than 50 percent show up to work, no more than half of them will be working by themselves.

“There are a couple other things I can tweak,” she says, “like whether people tend to prefer open or closed individual space, whether their meetings are mostly large or small, if they prefer their meetings to be open or closed.”

At the moment, no one is scheduled to occupy that addition, so it will be used as swing space for any department whose building is undergoing a renovation.

“Tell the biochemistry department and biology department, ‘We’re gutting your building for two years; that’s your space,’” says Serrato. “I feel certain that once people see it and start using it, they will like it.”

Columbia University’s Irving Medical Center is doing something similar by creating swing space as a pilot.

Another client of Serrato’s—a large university in the South—is constructing a $200 million engineering facility and struggling with the faculty about how to plan the interior spaces. That building won’t be designed for two years, so they have time to work out the details. Instead of debating with the faculty over assigned vs. unassigned seating, they are planning to operate eight activity-based pilot spaces on campus for smaller departments of fewer than 100 people.

Demonstration spaces like that can influence not only the occupants but others who become familiar with it. A post-occupancy study conducted by Cornell surveyed not only people using the space, but also people familiar with it but not using it: After four months, 3 percent said they thought it would work well; after nearly a year, almost 70 percent, said they thought it would work very well or extremely well. “That’s the power of a pilot,” says Serrato. “It demonstrates the benefits to everyone. And it’s a soft sell.

“Our goal is not to change the way people work by changing their workplace,” says Serrato. “People are already working differently. We just want to create a workplace that reflects that.”

By Lisa Wesel