Philadelphia-based Genesis AEC was able to reduce the square footage of a new translational medicine center of excellence by more than half and cut cost estimates by 16%, by reviewing the client’s needs versus wants; using innovative design practices, including a first-of-its-kind firewall design; and applying the approach known as “engineering, procurement, and construction management (EPCM).” The facility for a U.S.-based multi-national pharmaceutical company opened on Sept. 1, 2023.

The project involved the renovation of aging infrastructure within an existing facility with multiple vivarium spaces and research labs, and the construction of an addition on a very tight footprint and restricted site parameters. The renovation was completed while the current facility was still in use, so considerable care was taken to reduce the impact of construction on the animals housed there. The research animals aid in translational medicine, an interdisciplinary branch of the biomedical field that aims to bring together research and the scientific community to advance public health. The new facility is intended to improve vivarium capacity, reduce negative impacts from inefficient transport of animals to and from imaging and procedures, and improve productivity for both researchers and facility staff.

Applying EPCM as the First Step

Genesis was selected for this project in part because the client wanted to employ the EPCM strategy whereby all design and construction disciplines on the project team are involved from day one, when design discussions begin, until the day the client receives the keys. Even the selected equipment vendors are brought into early discussions rather than waiting until the facility is close to completion.

“Using EPCM gives the entire team a continuity of understanding, so that everyone knows how and why the design was developed, what that means from a scheduling and procurement standpoint, and finally how the design is intended to be executed in the field when construction management steps in,” says Tom Hughes, vice president of construction operations for Genesis.

The asset management services group within Genesis oversees procurement, which varies with each project based on the relationship between the supplier and the client, explains Hughes. “We always try to leverage our client’s procurement abilities when they have established relationships with suppliers, but there are times when it works best for us to complete the actual purchasing contracts,” he says. For example, if a supplier will not agree to a 90-day payment term required by the client, Genesis can make the purchase, then the client can purchase the equipment back from Genesis rather than directly from the supplier.

The project also had the advantage of access to 23,000 sf in a separate warehouse also owned by the client, which allowed the project team to avoid any potential supply chain slowdowns. “We were able to begin procurement very early in this project, which gave us the ability to store construction materials and even some lab equipment well before they were actually needed,” says Hughes.

Needs vs. Wants

“It can be a challenging dialogue when we are analyzing what the client wants, versus what we think actually fits their needs,” says Kevin Hollenbeck, director of design for Genesis. “In this case, we had a history of working with the client, so we had a good understanding of their corporate policies, but it is still always helpful to step back, be humble, and avoid any presumptions.” Hollenbeck adds that the design team asks a lot of questions at the beginning of each project to learn how the client currently works, what they are proposing to need, what their operational goals are, and what makes the occupants and facility processes unique.

Hollenbeck explains that the client originally said they wanted 90,000 sf for the addition. But after analyzing the needs of the researchers and staff, Genesis was able to show that 43,000 sf would suffice, ultimately saving $15 million in final construction costs that would have been incurred to build the facility originally envisioned by the client. Examples of space reductions achieved in the final design include:

- Sharing storage space among multiple labs rather than providing storage within each individual lab

- Enlarging prep space and the observation room so that these functions could also be shared by the three PET/CT scan imaging suites.

“As you look at opportunities for efficiency throughout every aspect of the project, you can usually very quickly shave off serious redundancies in square footage,” says Hollenbeck. “In this case, the site’s tight footprint meant that we needed to make every square foot as efficient as possible.”

First-of-its-Kind Firewall Design

Despite reducing the original design, the total square footage of the addition combined with the existing facility still exceeded allowable fire codes required in that state. Traditional firewall design code dictates that fire-rated walls be added to both the exterior wall of the addition and the existing structure’s wall, explains Hollenbeck. This essentially creates a fire-rated vestibule between the two buildings. To adhere to code, the vestibule must be large enough for each of the walls to contain solid fire doors that are separated by specific distances for accessibility.

“Using the traditional firewall approach in this compact site would have taken up very valuable square footage that just wasn’t available,” he says. “Instead, our design team came up with a new idea of how to approach the firewall that had never been done before on any of our projects or in that state.”

Rather than rating just the addition’s wall and having a reduced rating for the structure associated with it, they proposed to the township fire inspector that the whole structure should be rated to match the same criteria as the new wall. The result was that, regardless of which part of the building was on fire, all walls in the entire structure would meet code for a CMU 3-hour rated wall. The township agreed that although it does not follow the fire code as currently written, the solution adheres to the spirit of the code, and actually exceeds requirements for traditional two-wall fire systems.

“This approach went over so well there that we used the idea on another project in Kentucky,” says Hollenbeck. “Fire inspectors in Kentucky also agreed that the new approach is acceptable as a variation to their state’s fire code.” Based on this success, Hollenbeck expects to be introducing this new firewall concept to clients in other states when applicable.

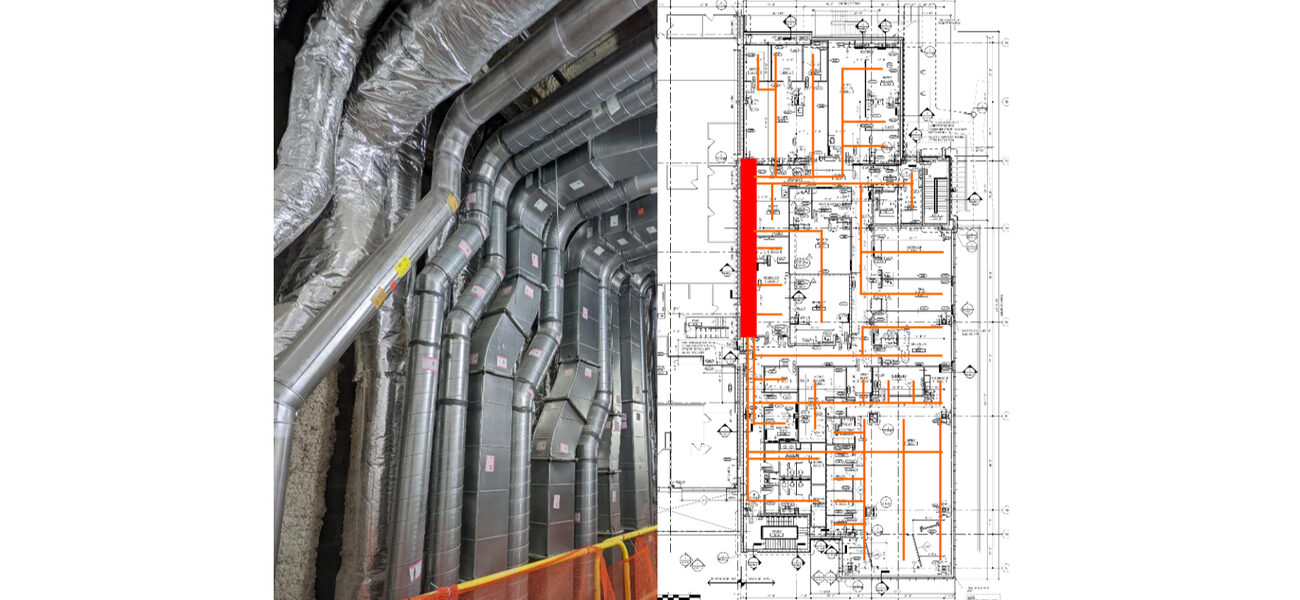

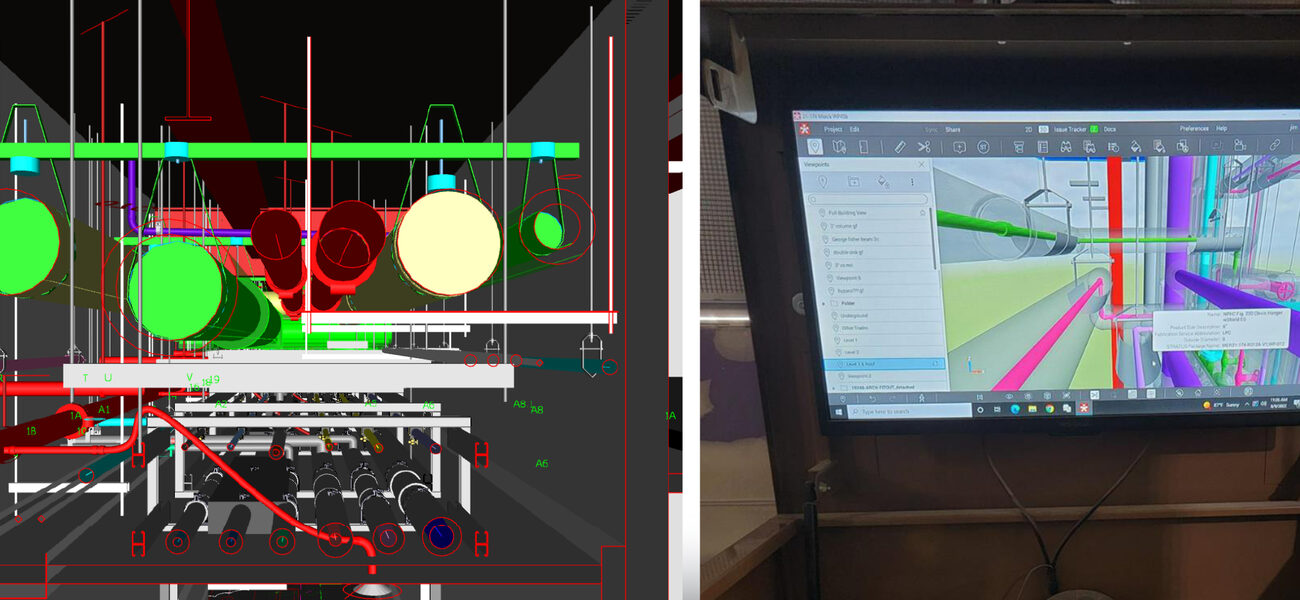

Creating a Master Shaft

By cutting the size of the facility from 90,000 sf to 43,000 sf, they were able to create a main building services shaft so that all systems are now fed through a single concentrated master shaft rather than having disparate shafts spread throughout the building. Hollenbeck warns, however, that this strategy will not work well for facilities much larger than this.

“Saving square footage by relocating the master shaft was not our intention, but it turned out to be an added bonus,” he says. “The primary purpose was really about trying to make the building more efficient for the client after occupancy.”

During early design discussions, the client’s facilities team commented that it was challenging to maintain the existing facility because it required traveling throughout various part of the building to identify which part of the system needed repair, or to perform general maintenance tasks such as balancing systems or filter replacement.

“Relocating the master shaft to one easily accessible row makes daily life much easier on the facilities team,” says Hollenbeck. “Now everything is easy to find and easily accessible so that systems can be calibrated, replaced, or repaired and in a safe and contained environment.”

The master shaft strategy also illustrated the project’s overriding objectives of increasing the efficiency of the facility through a better understanding of daily operations and updating outdated infrastructure to better align with the client’s long-term goals.

By Amy Cammell