Workplace occupancy planning used to be straightforward: People were assigned to an office, cubicle, or facility, and that is where they worked. Not so in the current hybrid work world. Traditional space and occupancy techniques are struggling to handle the complexity of today’s diverse facility use patterns. And increased pressure and regulations related to sustainability and energy usage only add to the challenge. However, AI is beginning to transform space and occupancy planning.

“AI can offer almost infinite analysis of massive data inputs far beyond what we can do as humans, and can create significant insights for space scenario planning,” says Brian Haines, senior director of strategy for OpenBlue at Johnson Controls.

Most facility operators already capture a significant amount of data. The continued advancement of AI provides an opportunity to harness these increasing volumes of curated data to think differently about the way buildings are used. Leveraging real-time and predicted space and occupancy data can optimize everything from HVAC and lighting usage to janitorial services and seating assignments. And the fully autonomous buildings of the near future are on everyone’s radar. “Before long, our buildings are going to be our partners rather than our problems,” says Haines.

Thinking Differently About Utilization

In the last decade, organizations have measured actual utilization of facilities using a variety of technologies: passive infrared sensors under chairs, overhead sensors to count people, flow counters to track entries and exits, badges swipes, and lighting control systems. Emerging technologies include a real-time occupancy monitoring system from XY Sense that offers insight into individual movements in a space. This expanding array of solutions can help space planners and facility operators understand, to an increasingly granular degree, how a building is used.

Haines is involved with a project that has been analyzing a sample data set produced by sensors installed in 20 million sf of building space to uncover utilization patterns around the world since 2019. One insight was that building utilization apparently has never really recovered from the pandemic. Utilization rates—people actually walking into a space and sitting down—had been hovering at around 40% before COVID. Post-pandemic, they seem steady at around 25% utilization globally, with North America’s rate significantly lower.

The project team then realized that they needed to think about utilization differently. “Coffee badging—when workers swipe their badge, grab a coffee, and go home—is a real thing,” says Haines. “In businesses that monitor only badge swipes, it’s an easy way to game the system.” The team also found that when you broke the data down by day of the week, utilization varied significantly. They separated out Monday and Friday utilization data (because fewer people went in on those days) and utilization levels rose to much more normal, pre-pandemic levels.

“We are on the cusp of a space planning revolution,” says Haines. “It’s already begun.” At FM: Systems (acquired by Johnson Controls in 2023), there is now a natural language interface to its Integrated Workplace Management System (IWMS). “It enables users to ask questions regarding space planning and get unbelievable answers back that used to require a data analyst, thanks to generative AI,” explains Haines. “It makes mistakes—I’ve seen them. But it’s getting better. It’s learning.”

Getting Smarter: The Path to Autonomous Buildings

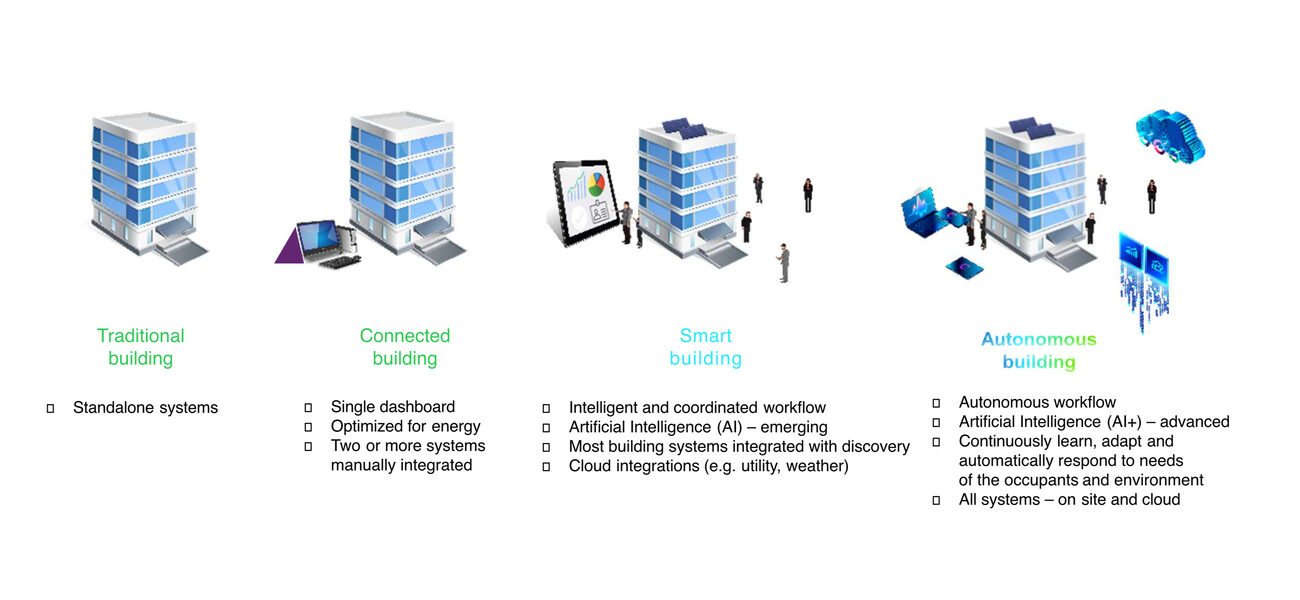

Beginning around 2020, connected buildings, outfitted with an array of sensors and meters that collect data and send it to the cloud, began to emerge. But it wasn’t easy to turn those data streams into actionable insights.

Now, we’re entering the smart building era. “If you’ve ever watched Star Trek, and you see the captain or a crew member ask the ship a question and get an answer, you have an idea of what’s possible in a smart building,” says Haines. “This class of building is connected, sustainable, healthy, and secure.” They are able to integrate data streams from connected devices and systems to offer more sophisticated insights, although it’s still up to humans to act on this intelligence.

Many smart building systems now have integrated AI capabilities. Johnson Controls, for example, introduced a new version of its Metasys building automation system where, for the first time, AI can diagnose and repair many common HVAC problems without intervention from a technician. “It is early days,” says Haines. “But it is happening.”

Haines predicts that, by 2030, we may see the first autonomous buildings come online. The AI-based algorithms that will learn, adapt, and be able to respond to events—for example, weather and security incidents—without the need for human intervention, are being developed now. That may sound scary, but the companies developing these systems are adopting strong, responsible AI frameworks with humans in the loop for now to keep an eye on what’s happening. “No one wants a building in Phoenix to suddenly think it needs to start pumping in heat in the middle of summer,” says Haines.

Embracing AI

To fully understand how these developments will benefit space planners, they need to understand AI. At the most basic level, says Haines, AI is just intelligence embedded into things like systems and software. “Then there is machine learning, which is where the magic happens,” he says. “You create an algorithm that can learn and get better over time.”

If you want to measure the utilization of a university campus, you might give AI access to sensor data. “If you start that on Friday, the machine learning algorithm is initially going to think that Friday is the most utilized day of the week,” says Haines. But that’s unlikely. College students tend to party on Thursday night, and very few sign up for Friday classes. “But if you continue giving the algorithm data from the rest of the week and you do that over and over again, it’s going to realize that the most popular days are Tuesday and Wednesday,” says Haines. “It learns over time.”

AI doesn’t just operate on its own, though. It requires space planners or facility operators to ask it questions before providing an output. That is why it’s important for space planners to start thinking about the problems that AI can solve for them. They are not going to be replaced by AI, but they need to embrace it. “It doesn’t matter whether or not we want AI to come,” says Haines, who worked as a space planner himself. “It’s already here.”

AI-Powered Space Use

Many companies are successfully using AI for stacking and blocking, but that’s just the beginning. The really juicy stuff will consider much more—commute time, temperature, the current building automation system, amenities, occupancy, user ratings of specific spaces—to optimize space planning and utilization, according to Haines. Examples include:

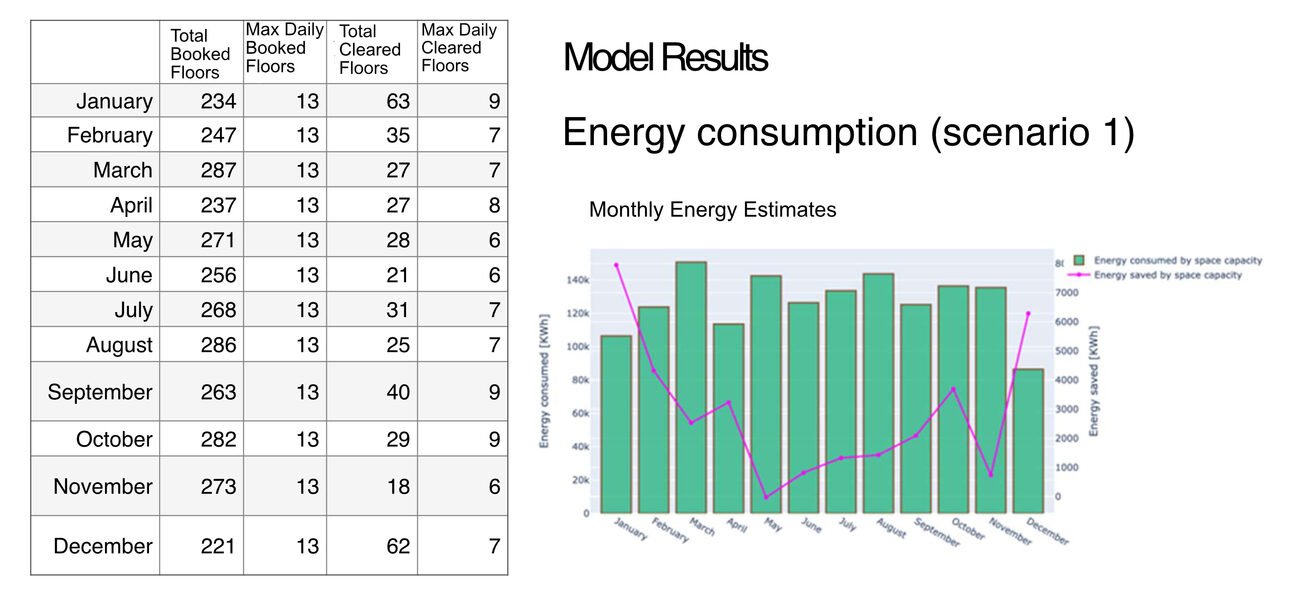

Low-utilization algorithms: A machine learning system can project when a space will hit specific utilization thresholds so it can, for example, turn the lights off or bring the heat or air conditioning down. Haines points to two European clients—a global bank and a global consulting firm—that tell their employees in London where to sit each day based on an AI algorithm. They know who their cohorts are, what amenities they like, and their light and noise preferences. They can then bring the building’s systems down or up slowly, depending upon projected utilization, and use the building control systems to shut parts of the building down to help them meet the EU’s stringent Energy End-Use Efficiency & Energy Services Directive (ESD) requirements

Outside temperature: A team of data scientists and AI programmers decided to look at real estate demographics—income levels, commute times, nearby amenities—as well as weather data in relation to utilization. Looking over an extended period of time, they found that for every degree increase in outside temperature, more people came in to work. Now they are developing a machine learning algorithm that can learn to forecast when people are going to come in based upon weather predictions. It will tell the building operator when it can close the tenth floor, for example, and just put everybody on floors one through nine, says Haines. One of the biggest operating expenses is related to the activities of the cleaning staff. “They turn everything on to do their work at night and, suddenly, at two o’clock in the morning, all the lights in the building are on but no one is there,” says Haines. Using AI, access to parts of a building is shut off, saving money not just in cleaning services and supplies, but energy costs. Office buildings spend an average of $1.51 per square foot in energy costs each year, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Dynamic restacking: Humans aren’t very good at recognizing extremely complex patterns. “You need a lot of data to achieve a high enough level of confidence to let the building turn itself off,” says Haines, noting that access to its predictive workplace management systems and large volumes of utilization data is why Johnson Controls bought FM:Systems; competitors have made similar acquisitions. “They all believe that the first one to get to an autonomous building will win the game,” says Haines.

Indoor air quality: Indoor environmental factors—predominantly light and sound—affect where employees choose to sit. “A person who likes the hubbub of the office may pick a spot that has a lot more noise,” says Haines. “But if you’re somebody who wants to focus, you may pick a spot that is quiet.” Temperature is another factor: Nobody likes to be too cold or too hot.

But the most fascinating factor Haines has seen lately emerged from analyzing data from stick-on WiFi indoor air quality (IAQ) monitors. “We had one conference room that everyone hated,” says Haines. The sensor revealed that when people went in that room, CO2 levels went through the roof. “When there is too much CO2—above 1,000 parts per million—you get groggy and you can’t think clearly,” says Haines. “It’s a terrible place to hold a meeting.” Conditioning spaces with proper air flow may the number one productivity investment an organization can make because it energizes people, according to Haines. Yet few companies measure CO2 levels.

The Real AI Risk: Not Evolving

Now is the time, says Haines, for space and occupancy planners to start thinking about the questions they need AI to answer, with hackathons, where developers team up with data scientists and AI developers to come up with such ideas. They are then given two days to develop a possible AI-powered solution, which is presented to a customer advisory board, and, if it has value, is developed into a product. “The speed of AI development is extraordinary,” he says.

AI can be a powerful complement to the work that space planners do, but it will not replace them. “It can start giving us hints like ‘Floor three of this building in September of this year is projected to drop below a certain utilization level, based upon the last three years of utilization data,’ and you can then start preparing for that, if you want, by making different decisions than you would have made before,” says Haines. “It can make us better at what we do.” And space planners can learn how to use AI-based tools quite easily because they use natural language. The real risk is for those who refuse to evolve along with the technology.

By Stephanie Overby