The University of Kansas (KU) faced a daunting challenge: more than 11 million sf of facilities in 150 buildings whose average age was 45 years and a deferred maintenance backlog exceeding $350 million. At the same time, the university’s strategic plan set a goal of increasing research and discovery, and the resulting campus master plan prioritized the need for new research facilities. Realizing that goal while addressing the existing challenges could have taken decades using traditional funding models. The solution? The Integrated Science Building, KU’s $180 million large-scale public-private partnership (P3) for interdisciplinary campus development, which is breaking new ground in funding models, integration, management structure, and fundraising activities. With this initiative, the university took a “great leap forward” in academic and research programs, design decisions, space allocations, programming, and critical infrastructure upgrades, as well as making a bold step with the project delivery.

KU’s situation is familiar to many state universities. The university had aging facilities overall, with the teaching and research spaces particularly outdated. The science facilities, built before the moon landing, had been remodeled over time to meet the evolving needs of the researchers, but the classrooms retained the traditional lecture hall design. For 20 years, the university was paralyzed by the price tag for replacing the science facilities, but they knew they needed to transform the way they taught and did research in order to avoid falling further and further behind.

Fine-Tuning the Plan

Nearly 10 years ago, KU wrapped up strategic planning and started its campus master plan, which included better student housing, dining facilities, a conference center with flexible meeting rooms, utility infrastructure to provide redundancy, and firm capacity to support the mission, as well as road and parking facilities. It was evident early on that the need for new science facilities was a high priority. Given the state’s history in approving projects, improvements at this scale could have taken more than 20 years to achieve, assuming the university could get legislative support. Tax dollars supporting higher education have declined for decades, but the Kansas Legislature did accept incremental increases in tuition to offset the state’s budget cuts.

The university had received financial support several years ago to expand its engineering facilities in an effort to increase enrollment, retention, and graduation rates. The growth of the engineering program would translate into economic growth in Kansas. KU’s total research expenditure has grown to $401.6 million in 2020, which provides a significant economic impact in the region. External research funding amounted to $275.4 million in 2020.

KU also raised its admissions standards. These strategies succeeded in improving retention and graduation rates, but still missing from the equation were the state-of-the-art facilities necessary to continue recruiting the best students, faculty, and researchers.

The 280,000-sf Integrated Science Building responds to that need. The master plan also includes:

- New central utility plant with an academic and research component

- New water and electrical services

- A 454-bed residence hall with a new dining hall

- 708 beds of apartment-style student housing

- New conference facility and student union

- Parking for 600 cars

The Funding Conundrum

Cognizant of the ever-increasing deferred maintenance backlog, university officials knew they had to budget for ongoing maintenance and operations of any new development going forward. Assuming a 4 percent annual rate of inflation, or $12 to $15 million per year, it was imperative to fast-track the project.

To take on a project as large as the master plan proposed—with a price tag of approximately $350 million, including $180 million for the Integrated Science Building—would require KU to leverage funding from multiple sources, including tuition; central funds generated from operational efficiencies; and revenues from housing, the student union, and parking.

The university evaluated the options for project delivery—design-bid-build, design construction management at risk, design-build, and public-private partnership. Given the complexities of coordinating all aspects of the development project, the P3 approach seemed to be the most efficient and effective.

State statute does not allow the sale of state property without special legislation. And transferring ownership would result in the loss of tax-exempt status, which would significantly increase the overall development costs. To use the P3 process while preserving its tax-exempt status, KU set up a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization and utilized the lease/lease back model, which is exempt from state sales tax and does not require any legislative action. KU leased the property to an affiliated corporation—the 501(c)(3)—the corporation contracted with the developer for the P3 services, and leased the completed development back to the university for a period of 30 years. Here’s how it works:

- The developer/architectural partners are responsible for design and construction, with the potential for an accelerated schedule. Construction cost and schedule risk are transferred to the private sector.

- The non-profit 501(c)(3) provides the project financing and is typically funded by tax-exempt bonds, which may initially lower the university’s credit rating slightly.

- The university enters into a long-term agreement with the non-profit (typically 30 to 40 years) and agrees to make lease payments in the amount of debt service and O&M costs. The university maintains ownership of the buildings.

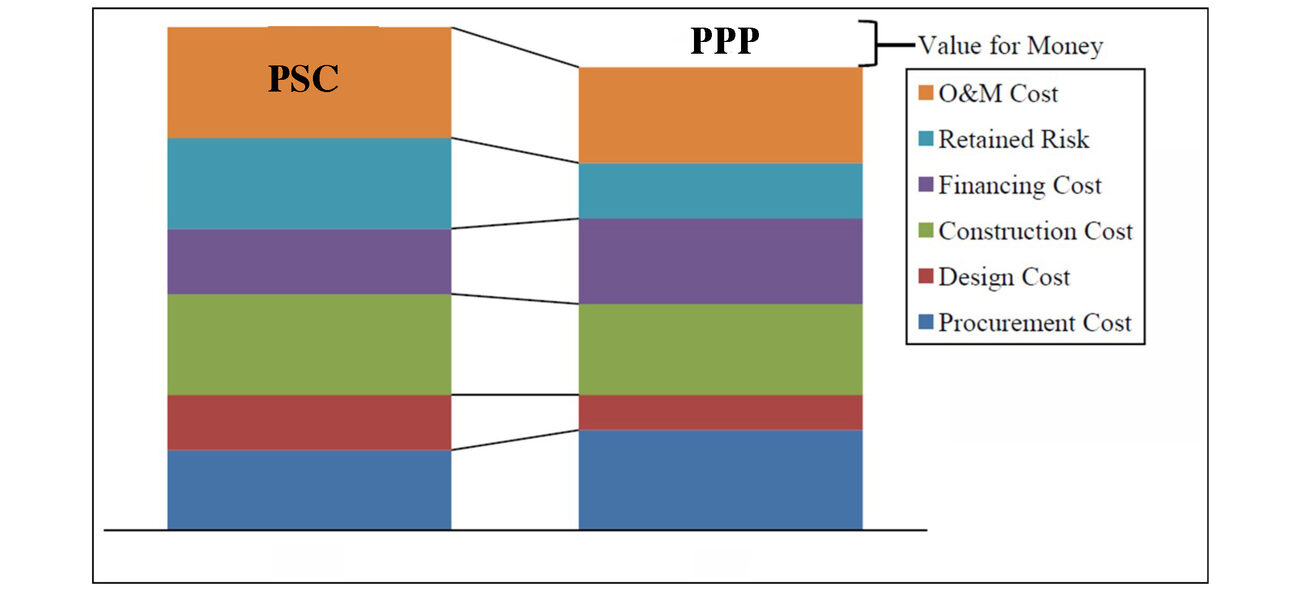

One of the aspects that made the P3 process attractive was the value for the money compared to competitive bidding. A Canadian study of P3 projects found that the arrangement resulted in 17 percent lower cost for educational facilities than the traditional design-bid-build process. Couple this with the savings on inflation, and it becomes a cost-effective solution to provide the facilities in a timely manner.

A number of design decisions made early in the process will result in long-term savings. Looking at a 40-year facilities cost analysis, from design to construction to operation/maintenance to refurbishment, over 80 percent of the total cost of ownership will be O&M and refurbishment. Early in the process, KU made lifecycle cost analysis a major factor in the selection of materials. For example, standardized lab modules with no dividing walls in the research laboratories will reduce remodeling costs in the future, as research projects evolve.

Operations and maintenance were also included in the P3 contract. Performance criteria were developed for daily O&M, and a minimum facility condition index was established for final turnover at the end of 30 years

P3 developments are highly flexible and can be variable. KU utilized basic procurement practices to manage the selection process. The initial request for qualifications (RFQ) was openly advertised, and qualifications were received by a prescribed date and time. A university committee assessed all the qualifications and selected the top three firms to be considered for the next step in the process, the request for proposal (RFP). Each firm met with the university to better understand its needs. To ensure that KU gets the most for the funding available, proposals were submitted with a base price and a price for tiers 1, 2 & 3 (priorities of additional scope of work). Based on the RFP submittals, the committee once again assessed the proposals and selected the finalist.

To keep the development a collaborative process, the affiliated corporation entered into an engagement agreement to participate in the design of the project. An intense five-month design process resulted in a set of design development documents and a confirmation of cost to do the work. The engagement process allowed for sharing the risk but more importantly, it yielded a design solution that both the owner and the developer are comfortable with. Each step in the procurement process helped build the partnership between the owner and the developer.

The Final Product

KU occupied the new Integrated Science Building in May 2018. Classrooms and class labs were lightly scheduled initially, to allow faculty and staff to learn the new systems and have a better understanding of the functional capacity of the new spaces. Transitioning the researchers from the old labs to the new facilities took a year to complete, much longer than anticipated, so the facility wasn’t fully utilized until the 2019 fall semester.

The academic classrooms largely emulate those in the Engineering Department’s Learned Engineering Expansion Phase 2 (LEEP 2). The university anticipates that the Integrated Science Building will generate a similar improvement in student performance, and increased retention and graduation rates. KU has seen a slight decrease in enrollment, but that can be attributed to a drop in international students. In the spring of 2020, the pandemic began to alter the way classes are taught. The resulting restrictions and changes in pedagogy in the last 18 months have not allowed KU to undertake an uncompromised post-occupancy evaluation of the facility’s performance.

The new facility brought not only new lab spaces, but a new research culture as well. KU established a performance-based approach to assigning researchers to the new Integrated Science Building, where they will no longer be confined by walls and private labs. The open lab modules allow research programs to expand and contract with minimal remodeling. It will take several years of data to determine the effectiveness of these cultural changes in managing research lab space.

By Jim Modig

Jim Modig is the retired university architect for the University of Kansas

| Organization | Project Role |

|---|---|

|

Edgemoor Infrastructure & Real Estate

|

Developer

|

|

Clark/McCown Gordon Joint Venture

|

Construction Team

|

|

Perkins&Will

|

Architectural Design

|

|

Affiliated Engineers, Inc. (AEI)

|

Engineering

|

|

Treanor

|

Housing Design

|

|

Johnson Controls Inc.

|

Operations and Maintenance

|