As an architect and director of facilities planning and operations at Florida International University’s Herbert Wertheim College of Medicine (HWCOM), José A. Rodriguez has directed and overseen the design of the school’s learning environments since its inception more than 15 years ago. But the institution’s recent interest in building active learning classrooms (ALCs) presented an opportunity to think differently about how to create spaces which support a different approach to instruction and interaction in the classroom. Figuring out what works and what doesn’t in terms of acoustics, technology, lighting, and sightlines has itself been a learning process. The biggest takeaway to date is that one must align the space—and the technology within it—with the pedagogy rather than the reverse.

“You have to fit the space to the program, not the program to the space,” says Rodriguez. “Define goals first and then determine how learning spaces can be designed to support those goals.”

Active learning, an instructional approach designed to increase student engagement, is on the rise at colleges and universities. Higher ed institutions have been building or retrofitting spaces incrementally to support more active interaction, problem-solving, and skill development, with classrooms where students put to practical use the information they’ve consumed on their own, instead of sitting in a lecture hall.

Rodriguez first dipped his toes into active learning waters in 2015. As one of HWCOM’s founding employees, Rodriguez had directed and overseen the design and construction of three lecture halls built to support the traditional “sage on stage” method of lecture-based instruction. Then in 2015, the opportunity to design a space for “training the trainer” came along. The resulting Innovation in Learning (iLearn) Lab serves six groups of five working together in a technology-enabled space, flexible enough to allow for different configurations depending upon requirements.

When HWCOM leaders, spurred on by an Association of American Medical College article citing the benefits of active learning classrooms, approached Rodriguez with an interest in building its first ALC, Rodriguez had already done quite a bit of study on the topic. Still, “I don’t believe our faculty knew what we were getting ourselves into at the time," he says.

A Lesson in Audience Engagement

The first medical schools in the U.S. were founded in the 1800s with a largely uniform method of instruction whereby medical students bought tickets to attend lectures. If it sounds like a bit of theater, it was. But while such tickets are now a relic of the past, the lecture-based approach to learning persisted.

ALCs, sometimes called flipped classrooms, turn that approach on its head. Rather than passively learning from an instructor at a podium, medical students engage with one another in smaller groups, practicing what they’re learning in real-life or simulated situations.

Rodriguez was fascinated by the idea from the start. When he mentioned it to his wife, a retired elementary and pre-K speech pathologist, she chuckled, as K-12 had long since adopted active learning protocols.

Today’s university students are former K-12 students who expect that level of interaction. “They need constant engagement and re-engagement,” says Dr. Stephanie Tadal, HWCOM director of instructional design and teaching development. “We have to think about setting up the environment and materials in a way that meets the needs of the learner, taking a more intentional approach to how we use the classroom space and the technology in the space.”

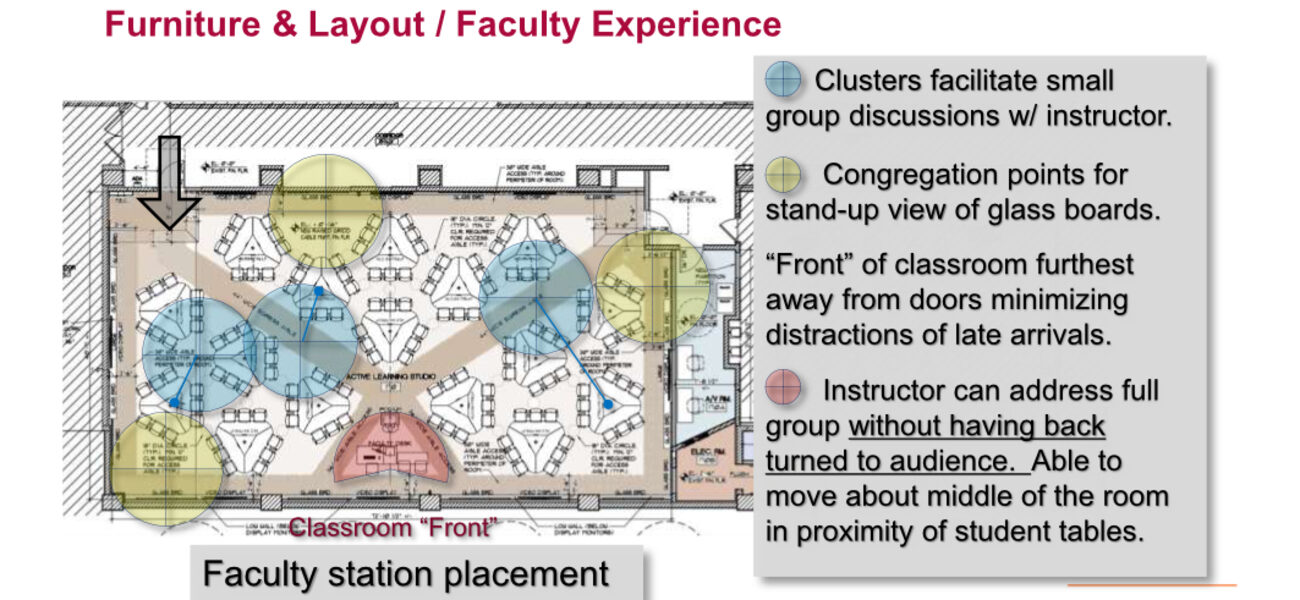

The goal of the ALC is to create an environment in which students “are up and manipulating the environment, and the faculty are walking around checking in on their progress,” says Tadal. The question for Rodriguez was how the form of the classroom would need to change to adapt to this different instructional paradigm.

Big Changes, Small Footprint

Rodriguez started planning the College of Medicine’s first ALC in February 2020 with the remodeling of a tiered auditorium built a decade earlier. The biggest challenge was available real estate and “fitting the proverbial 10 pounds of merchandise into a five-pound bag,” says Rodriguez. Once the auditorium was demolished, it would leave 2,840 sf of space for the ALC.

Early on, Rodriguez settled on triangular tables he’d seen used at another medical school. They required significantly less circulation space than round tables, and the geometry itself made it easier for group members to interact with one another.

In working with Dr. Tadal, Rodriguez understood that the ideal group size for active learning was five to seven students. However, the available footprint couldn’t accommodate enough six-person tables to fit 144 students, leaving the 16 nine-person tables as the only viable solution. “Smaller tables would have been great,” he says, “but there was no way to achieve the desired capacity and still satisfy all of our other requirements.”

An 80-Decibel Problem

During the course of an ALC session, faculty equipped with wireless mics and remote media control buttons can walk around the room and address the entire class. Students likewise can use a push-to-talk function at their tables. All the technology works well; everyone can be heard.

The nature of an ALC, however, calls for a good portion of time spent in small group activities. The med students may be given a problem to discuss with their peers that they then share with the whole classroom. The sound levels generated when 16 tables were engaged in the classroom was off the charts. Normal conversation registers around 60 decibels (dBs). During small-group discussions, Rodriguez saw the noise levels settle in the high 70 dB range with frequent spikes into the mid-80 dBs, according to his National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) mobile app. “A ringing telephone is 80 decibels,” says Rodriguez. “The problem is, as groups try to speak over each other, it evolves into an ever-increasing crescendo.”

With many of the wall surfaces taken up by monitors and whiteboards, there was little opportunity for acoustical dampening. Instead, Rodriguez is testing a sound-masking feature in the speaker system, controllable from the Crestron® panel. It creates a background noise that renders speech at other tables unintelligible, mitigating the need to raise voices.

The Right Lights and Clear Lines of Sight

Another issue with ALCs is making sure everyone can see the display monitors and screens. Unlike an auditorium with fixed, unidirectional seating oriented toward a central source of content—the instructor and a screen—an ALC has more flexible seating oriented in different directions around the room, multiple media sources, and a floating instructor.

First, Rodriguez had to take those reflective display monitors and glass whiteboards into consideration in the lighting design. There are three or four zones of customizable, dimmable downlights. These shed less light on perimeter walls, resulting in more vibrant colors on displays and less eye strain. While there are house lights available for general ambient illumination—for use when the classroom is cleaned, for example—Rodriguez tells faculty to avoid them while using a PowerPoint presentation, to prevent glare and washed-out colors on the room’s 98-inch monitors.

To establish unobstructed sightlines to media, Rodriguez had to evaluate each student station group and rotate the triangular table's orientation as needed. When first designing the space, the architectural firm neatly organized the tables, but it didn’t work. “You can’t just place these tables in a room; you have to plan their orientation,” he says. “We had to plot the line of sight to a monitor or screen and rotate the tables slightly in order to provide each grouping of three students an optimal sightline. Most people wouldn’t notice that the tables are not all aligned in the same direction.”

Unexpected Use Cases

Rodriguez has now built two ALCs at HWCOM. From a demand perspective, they’ve been a roaring success. They’re booked solid, and their inherent flexibility has opened the door for a variety of unplanned uses, such as demonstrations using simulators.

The medical school uses Harvey® cardiopulmonary patient simulators designed to demonstrate the symptoms of nearly 50 different cardiac disease scenarios by varying blood pressure, pulse, heart sounds, murmurs, and breath sounds at the touch of a button. In the past, the director of the simulation center had to demonstrate the simulator’s operations to small groups of students, one group at a time. “Now the instructor can cover the general instruction of a full cohort at one time with the aid of cameras, which have tilt and zoom capabilities, and use microphones to pick up simulator sounds,” says Rodriguez. Students then move upstairs to the school’s simulation center and work with standardized patients or with other simulators.

“What I find gratifying is that the faculty can innovate and fully utilize the room in unexpected ways,” says Rodriquez. “The ALC design is showing more flexibility than we even anticipated.”

Fitting the Space to the Program

Many higher ed spaces are not intentionally designed for the learning that takes place there. “For many years, we have retrofitted the way we teach to work within a space or to use a certain technology,” says Dr. Tadal. “We haven’t started with the goal of the lesson or the course or the program in mind.”

Many colleges and universities will buy classroom technology before they know how they plan to use it. The problem is only exacerbated by computer-aided architectural design software, which Rodriguez says empowers architects to quickly assemble spaces without thinking through how they will work in real life.

With ALCs, there’s an opportunity to do things differently, but some of the solutions were hard-won. There was a faculty expectation, for example, that there would be intense use of glass boards and smartboards during sessions, but that hasn’t been the case. That underscored the importance of being clear about how the space would be used and then selecting the technology. “We didn’t challenge that assumption, and filled the walls with them,” says Rodriguez. “Technology in the classroom can be extremely expensive in pursuit of the latest gadget, at risk of underutilization. Remember, technology is obsolete within eight to 10 years.”

Designing for the pedagogy can be a more painstaking process start to finish, and even beyond. Rodriguez plans to launch surveys to assess student and faculty satisfaction and experience with the new spaces. “An ALC requires significant integration and attention to details,” he says. “Do not underestimate the complexity from the planning and design stages, through execution.”

By Stephanie Overby

Additional Resources:

A. Finkelstein, J. Ferris, L. Winer, and C. Weston, “Principles for Designing Teaching and Learning Spaces” (Teaching and Learning Services, McGill University, 2014).

Anastasia Morrone, Anna Flaming, Tracey Birdwell, Jae-Eun Russell, Tiffany Roman, and Maggie Jesse, “Creating Active Learning Classrooms Is Not Enough: Lessons from Two Case Studies,” EDUCAUSE Review, December 4, 2017.

Katie Bush, Monica Cormier and Graham Anthony, “A Rubric for Selecting Active Learning Technologies” EDUCAUSE Review, April 28, 2022.