As health science education becomes increasingly interprofessional, the design of academic medical facilities is changing to reflect this new type of learning. Collaboration is the cornerstone of interprofessional medicine, as health care providers strive to offer the best patient care. Nurturing such collaboration begins in the educational facilities where students from multiple disciplines learn the importance of working together.

“In team-based, patient-centered care, it is about the patient,” says Scott Kelsey, managing principal at CO Architects in Los Angeles. “We believe that starts in the educational setting, so we want to create a larger cross-section of environments to support health science education teams.”

Drivers for Interprofessional Design

During the past 10 years, CO Architects has designed more than 1.5 million sf of health science education space. Interprofessional design concepts are powered by four key drivers: sharing resources, leveraging space efficiencies, increasing and improving collaboration, and benefitting team care.

Institutions want to maximize capital resources by creating opportunities to share space. Certain discipline-specific spaces—task labs in a simulation room, a nursing clinical lab, and a pharmacy compounding lab—must remain separate and be used only for their intended purposes. However, approximately 90 percent of program spaces can be shared across disciplines, including those used in the primary areas of medicine, nursing, pharmacy, and allied health. Sharing has the potential to provide access to spaces that might otherwise be too costly to build or operate independently.

“A potential benefit of sharing space is increasing space utilization. Health science programs have relatively lower utilization when compared to higher education in general,” says Kelsey. “This is due to the unique curriculum, clinical faculty schedules, and clinical activities. There are opportunities to leverage space use.”

Sharing space—such as classrooms, lecture halls, learning studios, offices, bookstores, cafeterias, group study rooms, exam rooms, wellness centers, libraries, lounges, and public access terminals—can facilitate more effective collaboration. This means creating facilities that foster formal and informal collaboration to support the exchange of knowledge and ideas, strengthen relationships, and develop greater respect between professions and disciplines.

“Ultimately, the driver for integration is to improve patient care and safety by improving the quality and strength of the care team,” says Kelsey. “We are trying to create the same type of teamwork in an educational setting that will take place in a clinical environment.”

Learning in a Team-Based Environment

Students learn differently today than they did years ago in terms of the tools they use and the environments where they are taught. Learning is a social process that requires a large range of environments where information can be properly communicated by instructors and applied by students. This means learning spaces are more diverse. For example, a lecture hall can be designed to be both didactic, with an instructor standing in front of the room, or more interactive, where the instructor and the students work together.

Today’s educational models require more learning studios, a flexible, flat-floored environment where the instructor moves throughout the room rather than standing behind a podium. There is also a growing interest in small group rooms.

The interprofessional educational model also features a lot of competency-based training spaces, where teamwork can occur across the health sciences disciplines. For instance, there are areas for simulation, skills training, study space for small or larger groups, and collaboration environments, where students and faculty can interact in an informal setting.

Designing Integrated Facilities

The key to providing interprofessional learning is offering integrated facilities that foster sharing, collaboration, and teamwork. CO Architects works under the philosophy that integrated facilities have four primary characteristics:

- The institutional vision of the level of integration a client is trying to achieve, whether it is interprofessional, multi-institutional, or integration into the community;

- The level of connectivity throughout the campus, with surrounding buildings and communal space;

- Program vision and level of integration, which equates to the number of resources that will be shared, and whether curriculums will be kept separate or shared; also considered may be a transdisciplinary program, where research and clinical space are located in the same building with shared resources;

- The qualitative and programmatic design concepts that are needed to create diverse, adaptable learning spaces; the proper student space program; significant clinical skills program; and maximum transparency and permeability.

“We define transparency as the ability to see into and out of program spaces. One important feature of successful integrated buildings is the ability to observe active learning and research on display wherever appropriate,” says Jonathan Kanda, an associate principal at CO Architects. “The strategic use of glass is the most obvious design tool for achieving this, which must be balanced with acoustics, privacy, and security concerns. The other notion of transparency is about clarity of the building organization; making obvious the disposition of program elements; and signifying where formal learning, informal learning, socializing, and meaningful collaboration can occur.”

A central building feature, such as an atrium, forum, or courtyard, can create a communal space and unify the entire spectrum of programs. Such a feature is advantageous in large interprofessional buildings.

Case Study #1: Education Resource Center at the University of Virginia

The ERC, currently in design and slated for completion in April 2015, will be a 35,000-sf facility that integrates education and clinical programs on one small site in Charlottesville. The program will bring together an outpatient pharmacy, outpatient imaging, graduate medical education space, simulation, and meeting rooms.

It is referred to as a “bridge building” because it completes the connective pedestrian circulation system. The ERC is part of a master plan that will link the new cancer center to the rest of the campus, which includes the University of Virginia Medical Center, the Claude Moore Medical Education Building, and the education and research facilities. Even parking is linked throughout the campus to provide easy access to all buildings. The university wants those linkages to be demonstrated using glass to convey the concept of transparency and to show people moving from destination to destination.

The program distribution at the ERC will consist of approximately 60 percent clinical space and 40 percent for other educational purposes. A major challenge in integrating the education and clinical programs is dealing with occupants who prefer some degree of separation. CO Architects experimented with numerous stacking schemes to determine what floor plan and building layout made the most sense.

“We realized there are three fundamental tasks happening in this integrated building: education, simulation, and patient care,” says Kanda. “The educational meeting room provides the best opportunity for sharing by being used by residents and fellows, patients or the community, faculty and staff, and the hospital board.”

The ERC floor plan utilizes the entire lower level for the imaging suite. Simulation and the pharmacy are located on the first level, which is at street level to provide easy access for patients. The second level will feature a large flexible meeting room and offices for graduate medical education. Transparency will be especially noteworthy on this floor, which features many large windows.

The meeting room on the second level will be scalable and adaptable to accommodate a variety of purposes for different users. It could be used in a large lecture format or could be broken down into smaller spaces to host everything from a large meeting, conference, entertainment or small group activity.

The meeting room will be equipped with furniture that is flexible, movable, and stackable to facilitate storage. Movable partitions will be used to divide the large room into sections, when necessary. A technology platform will accommodate the various iterations of space size, layout, and learning modality.

Case Study #2: Health Sciences Education Building at the Phoenix Biomedical Campus

The 264,000-gsf building, completed in July 2012, represents the next step toward an interprofessional education model that ultimately supports team-based care. The facility is shared by the University of Arizona (UA) College of Medicine, the UA College of Pharmacy, and Northern Arizona University programs in physician assistant, physical therapy, and occupational therapy.

“It moves beyond the traditional educational silos by providing shared space used by these different professions,” says Kelsey. “In some instances, the curriculum is also starting to support interprofessional teaching. Gross anatomy, for example, merges medical and physician assistant students.”

The spaces are diverse, ranging from one-person study rooms to lecture halls that can accommodate approximately 150 people. CO Architects collaborated with a space utilization consultant to determine details, such as how many classrooms were needed.

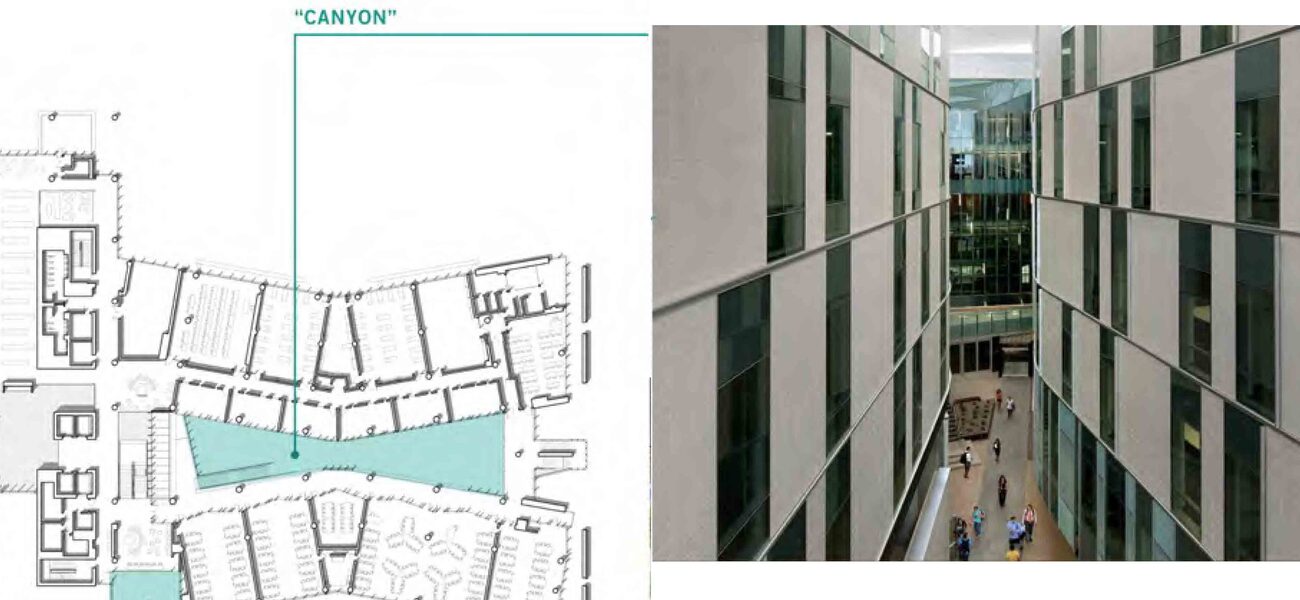

The ground level features the entrance lobby, a café, lecture hall, gathering spaces, and outdoor “canyon” space. The so-called canyon is a protected exterior space that is framed by the wings of the building, but is open on the east toward the street. The canyon, inspired by the natural canyon formations in Arizona, serves several integrated functions: It provides usable exterior space for informal gatherings and university functions, creates an organizing feature that facilitates orientation and wayfinding, and brings diffused daylight into occupied spaces. The building’s air handlers send cool air into the canyon to offset the extreme Phoenix heat.

Also located at ground level is the mixing bar, where students, faculty, staff, and visitors can mix in unstructured ways, as opposed to the structured interaction that may occur in the classroom and learning environments.

“Physically, the mixing bar is the building wing that runs in the north-south direction and connects the structured learning spaces housed in the north and south bars of the building,” says Kelsey. “Programmatically, therefore, the mixing bar contains those elements common to all users: lobby, building core elements (stairs, drinking fountains, elevators, etc.), food service/café seating, student lockers, shared student lounges, the library, student government suite, and small meeting rooms.

Case Study # 3: Collaborative Life Sciences Building & Skourtes Tower

The 612,000-sf building at Portland State University, completed in July 2014, is a multi-institutional partnership with the Oregon University System, Oregon State University, Portland State University, and the Oregon Health & Science University. It integrates medicine, dentistry, physician assistant programs, biomedical research, pharmacy, and undergraduate sciences. The building is intended to provide space for education, clinical, and research.

Many of the classroom spaces are utilized by multiple disciplines. The lecture halls, learning studios, and some of the small group rooms are scalable and can be divided to accommodate varying numbers of people.

The building layout features a street level with an inviting atrium, retail shops, and food services. The second level is dedicated to teaching spaces, but also includes a 400-seat lecture hall, and small group rooms. Research labs are located on level four, with plenty of glass to provide a view into the mixing bowl atrium space below. Offices, clinical skills, and simulation facilities are typically clustered together to promote collaboration.

“The clustering concept was presented as part of the planning and design of the clinical skills and simulation facilities,” says Kanda. “Clustering facilitates shared, simultaneous use of the simulation center by creating independent, self-sufficient clusters consisting of two simulation labs, a control room, a debrief room, and support space. Each cluster is somewhat isolated from the others to minimize cross-traffic disruption in the corridors. The clusters can be used by the same group or by different schools and departments.”

On each floor, there is a communal area where users can eat lunch, use technology, or just gather. The learning resource center is an information commons used by students, educators, and staff.

“Even in highly collaborative team-based environments, students still need a space where they can go and focus,” says Kanda. “A student-only lounge gives students their own space.”

Planning for Tomorrow’s Projects

The focus of interprofessional education facilities is to create environments for collaborative, team-based learning with the intention of improving patient care. Integrated, shared facilities leverage space, capital, and intellectual/cultural synergies. Diverse and adaptable spaces are the hallmarks of successful integrated facilities.

Lessons learned include:

- The design can focus on student and faculty who work across education, research, and/or clinical functions by creating direct circulation paths between the disciplines. The circulation may be programmed with breakout space.

- Transparency can create appropriate visual connections while maintaining physical separation.

- Providing common space brings people out of their respective domains into exterior space, contemplative spaces, a large forum/meeting space, food service and retail areas, meeting rooms, lounges, and breakout space.

“Research, education, and clinical activities all have unique programmatic requirements that often conflict with the idea of further integration,” notes Kanda. “When integrating research, education, and clinical spaces, you must respect the inherent boundaries, but also identify the common activities that might link them together.”

By Tracy Carbasho

This report is based on a presentation given by Kelsey and Kanda at Tradeline’s Academic Medical and Health Science Facilities 2013 conference.

| Organization |

|---|

|

CO Architects

|