Universities have always been magnets for scholarship, but they increasingly act as magnets for economic development and community-building, as well. This trend has enormous implications for the future of learning, work, and real estate, as academic anchors look to leverage their ideas and the neighborhoods around them to generate entirely new industries and communities. The resulting developments, anchored by deep and diverse talent pools, in turn attract employers who are eager to collocate with universities to tap their resident brainpower.

In these converging trends, Adam Glaser, Planning+Strategies leader at Perkins+Will, sees a solution to the chronic shortage of affordable real estate that is often a stumbling block for budding entrepreneurs, proposing a novel approach to innovation space based on large networks of shared workplaces anchored by academic institutions.

“Universities today are expanding their missions to focus on lifelong learning and entrepreneurship, and this has vast placemaking implications,” says Glaser. “In the old academic model I call ‘Campus 1.0,’ students attended a college or university largely to credential themselves for a traditional, linear career. After graduating and getting jobs, these students typically moved away, leaving a transient, often underperforming college town behind them. Today, many students and alumni are choosing to settle in academic districts, remaining there for an extended period of time after graduation, whether for further training or to stay connected to their network of faculty and other mentors who offer access to partnering opportunities and potential investors. I refer to this new model as ‘Campus 2.0,’ and to the phenomenon of graduates remaining near their alma maters, ‘upward immobility.’”

As this paradigm takes hold, it’s leading many companies to collocate in university communities to be near an emerging place-based, well-educated workforce. At the same time, it also leads schools to take a greater interest in work itself, training people and studying how they work.

“In the Campus 2.0 model, universities, municipalities, and businesses amplify these trends by collaborating to create large shared workspace networks—a variation of current coworking models—where people can be educated, get employed, and stay connected,” he says. “And as national investment in research decreases, these new innovation ecosystems may also address funding shortfalls, by using coworking models to generate revenues that can be reinvested in programs, research, innovation, scholarships, or community outreach.”

How Commercial Coworking Misses the Mark

According to Glaser, there is a growing disconnect between commercial real estate (CRE) and the kinds of flexible, low-cost spaces that support innovation.

“People who participate in the gig economy or think about starting their own companies are rarely in a position to act as ‘credit tenants’ for major new construction or existing Class A space,” he says, wryly observing that “‘innovation’ is often code for ‘people who can’t pay rent.’

“This is a really serious challenge,” he continues, “because, despite large numbers of emerging entrepreneurs and all the hopes we have riding on their success, we often don’t give them the support and resources they need, and this includes space and real estate.”

Coworking space has been hailed as the bridge that spans this great, primarily financial, divide. It’s significantly lower in cost, move-in ready, scalable, and well-equipped with lifestyle amenities. Factor in active community management, and the social dynamics present promising opportunities for synergistic collaboration.

However, while often billed as a vehicle to fuel further innovation and entrepreneurship, at its core, coworking space is still a variant of classic real estate business models. Coworking chains act as credit tenants to lease huge blocks of space and then reconfigure them, leasing their spaces back to smaller entities at what amounts to a significant mark-up, explains Glaser. “For coworking operators, their gross revenues can be two to three times more than the base rent they pay, which can present opportunities for a significant profit. In the CRE industry, this process is known as ‘lease arbitrage.’

“Arbitrage is the delta between the rent you pay and what you get in net revenues,” he says.

While coworking remediates some of the affordability crunch, it still tends to benefit its investors more than its customers, and like conventional CRE, most coworking spaces are speculative, often built without specific tenants in place, which can present risks for both operators and their investors. To put it another way, today’s shared workplace market remains largely supply-driven in ways that arguably limit the amount of space recent graduates and entrepreneurs can access as they look to start their businesses.

This recognition prompts Glaser to ask, “What if universities, alumni, and entrepreneurs could team up to hack what is effectively a multi-trillion-dollar global market for commercial real estate, to advance mission-driven outcomes like learning, innovation, social equity, and sustainability?”

Campus 2.0 + Subscription Real Estate

This hack might be what Glaser calls “subscription real estate,” an emerging concept that “adopts coworking functionality, but returns any arbitrage back to the institutions and people, particularly innovators and entrepreneurs, who need space and funding to do wonderful, promising things.”

Subscription real estate turns the tables on speculative, supply-driven coworking, looking instead to leverage the vast demand for innovation space that a broad academic community can assemble and aggregate into pools of people who “subscribe” to the anchor’s spatial network.

“Subscription real estate can happen wherever an anchor or other affinity-based entity can essentially create its own demand for space.”

Consider the fact that any academic constellation includes tens of thousands of people who need workspace—students, graduates, faculty, partners, affiliates, entrepreneurs—a group that Glaser refers to as a school’s “talentshed.” Taken as a whole, a talentshed represents “an incredible amount of demand” that anchor institutions can leverage to great advantage. For instance, most universities have a living alumni base that’s approximately 10 times larger than the number of students it enrolls in a given year, so this demand pool often numbers in the hundreds of thousands of people, for large or even mid-sized schools. Factoring in industry partners and outside demand—if even a relatively small fraction of alumni, partners, and faculty choose to participate in the university’s subscription CRE network—it can generate millions, in some cases, billions of dollars of potential revenue.

Imagine a distributed network of university-branded spaces near the main campus, with several networked satellites in key metro markets like New York; Washington, D.C.; or the San Francisco Bay Area. For students, alumni, and partners, this would present a low-cost, highly flexible platform to work and network in several critical places, with access to life-long learning, and entrepreneurial and social amenities that expand on their classic four-year 1.0 degree. For the institution, it would dramatically strengthen its alumni network and the school’s impact as a hub of lifelong learning and innovation. And for real estate providers and developers, it would represent a larger, stable demand basis to advance innovation district developments with greater density and shorter timeframes.

And unlike conventional coworking operations, universities—or even networks of universities—can tap their talentsheds directly in ways that avoid the extensive and expensive sales and marketing outreach often necessary to fill commercial coworking space. This strategy can also eliminate the need to provide such high returns to investors, as schools can choose to leverage or arbitrage their own facilities for the good of the institution and its mission.

Once a university calculates its talentshed, it can determine how much potential space it may need from a demand point of view, and then approach landlords and developers to offer significant revenue streams that are effectively securitized by the subscription model. Ideally, it’s a bit of a win-win-win: Entrepreneurs and contractors pay a lot less for better space; far more people gain access to talent and support; and landlords see higher, more stable returns. What’s more, the sponsoring organizations can take any arbitrage and put it back into program funds, scholarships, community outreach—even their endowment.

The 12 Square-Mile Maps

Many of the ideas behind Campus 2.0 and subscription real estate come from years of studying and working on innovation district plans, particularly Kendall Square, directly adjacent to MIT.

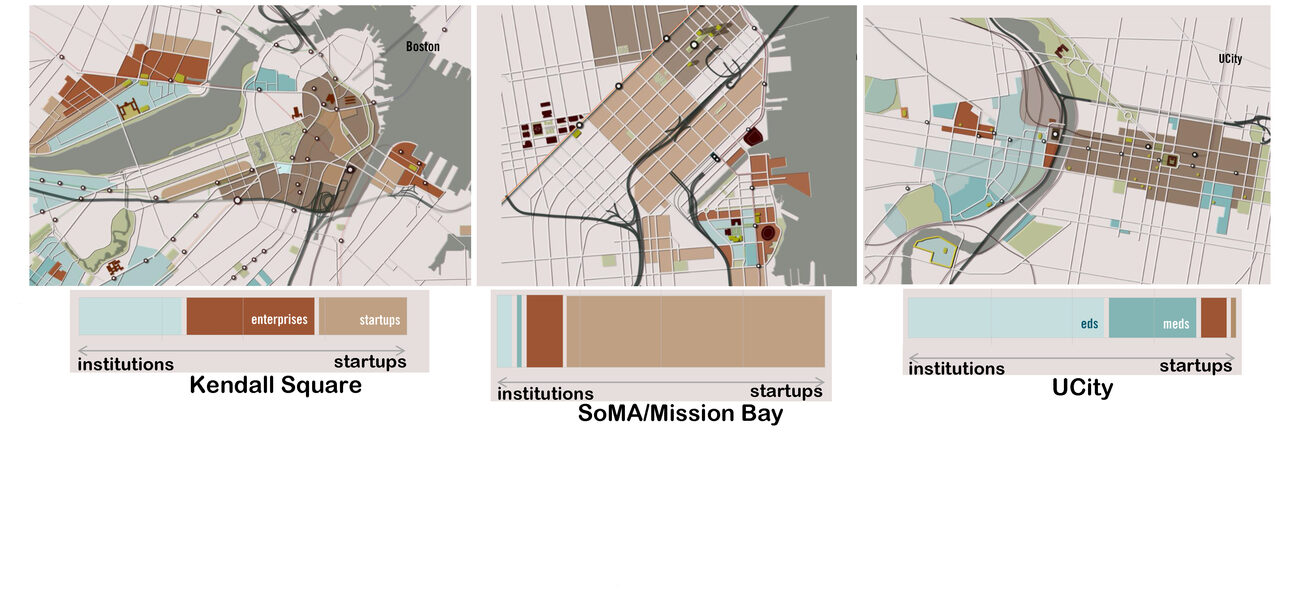

As Glaser worked in innovation districts around the U.S., he began a practice of creating “12-square-mile maps” of these communities to better understand their land use patterns and the relationship of academic anchors to the businesses around them. Focusing on a walkable area measuring three by four miles, each map is overlaid with the innovation players in the local ecosystem, “so people understand the physical relationships.”

“I study all sorts of iconic areas that people refer to as innovation districts, and I break them down into four components: How much space they provide for startups, notably in coworking and incubator spaces; for enterprise businesses; for universities, which play the convening role; and in certain instances, related healthcare facilities.”

Along with finding “incredible spatial and planning diversity in what we identify as the innovation space,” he notes the most successful places typically also have the most coworking—but not the commercial coworking variety, rather hybrid models driven by the universities to advance academic-industry partnerships. “We are seeing a completely different type of animal,” he says. In Kendall Square, the key shared workplace anchor is the Cambridge Innovation Center (CIC), which has grown exponentially over the years and also spread to other U.S. cities like St. Louis and Philadelphia.

To illustrate, he uses the example of Boston, whose 12-square-mile map includes the thriving Kendall Square development, a large swath of which is owned by MIT in neighboring Cambridge, well known for its dense concentration of entrepreneurial start-ups and acclaimed for its innovation success.

But Kendall Square is only a part of the picture. The Boston ecosystem is full of “garage districts, messy wonderful places” that are typically affordable because they are not located in prime areas or tied to new construction. When Mayor Thomas Menino proposed creating a new innovation district in the Boston Seaport area, he tapped the CIC to help anchor the new development. This led to the District Hall project that was instrumental in providing event and coworking space to get the fledgling district off the ground.

“This type of facility allows entrepreneurs to gather, experiment, and succeed or fail fast, without the pressure of having to write a big check for rent. As these spaces begin to spread, we are starting to see greater demand for these sorts of alternative spaces, often in conjunction with coworking functionality.”

It is not just start-ups but large employers who are increasingly moving to where the talent is. Looking at other cities through the Campus 2.0 prism, Glaser cites the development initiatives that have been taking place around Arizona State University in Tempe. Attracted by ASU’s recently created actuarial science program, as well as available land and other amenities, two major insurance companies—State Farm and Nationwide—have established a strong presence in the area.

Glaser quotes a recent remark made by a leader in ASU’s real estate group that summarizes the university’s approach: “We gather people together and put buildings around them.”

“I don’t think any university thought of itself that way 15 or 20 years ago,” says Glaser. “A handful of schools are now beginning to have this ‘eureka’ moment as it dawns on them that they can play a catalyzing role, not only in pedagogy but also in collocating and growing new businesses.”

The vision that emerges from this trend is “a future model of our economy where universities convene a wide range of stakeholders to promote new ideas and work models, as innovation becomes increasingly embedded in higher education. More and more employers will choose to locate in university communities, as opposed to being off to one side. We are going to see a new kind of workplace, where both the academic workplace and corporate workplace converge.”

Campus 2.0 Toolkit

To universities looking to build an ecosystem of lifelong learning, innovation, and industry partnerships, Glaser offers a four-pronged Campus 2.0 toolkit, divided into “culture” and “placemaking.”

In the first category is enhanced anchor engagement, as exemplified by the way “MIT actively assembled and curated acres of adjacent land and underutilized development assets to create a community of innovation in today’s Kendall Square.” This is followed by a willingness to partner, or convergence, which requires anchors to actively embrace an ever-wider range of stakeholders and potential industry and community partners. Extreme reuse/extreme affordability, as reflected in leveraging undervalued properties and sites and existing structures for affordable and accessible facilities, falls in the placemaking category; as does the last tool, CRE change agents, an active commitment to advance innovative spatial and economic strategies like subscription real estate, to accelerate their development capacity and impact.

In this way, innovative real estate becomes part of the university’s placemaking and community-building strategies, a resource that can be marketed to alumni, faculty, and partners nationwide. Glaser advises that institutions that want to pursue Campus 2.0 initiatives will have to do their homework, looking at things they’ve never thought about before, asking, for instance, what kinds of facilities are necessary to support a life-long “post-graduate” community—mixed-use, transit, K-12 schools?

“This is a critical process moving forward,” he observes.

The Future: Networked Institutional Real Estate Portfolios

What would a Campus 2.0 “plan” or strategy look like?

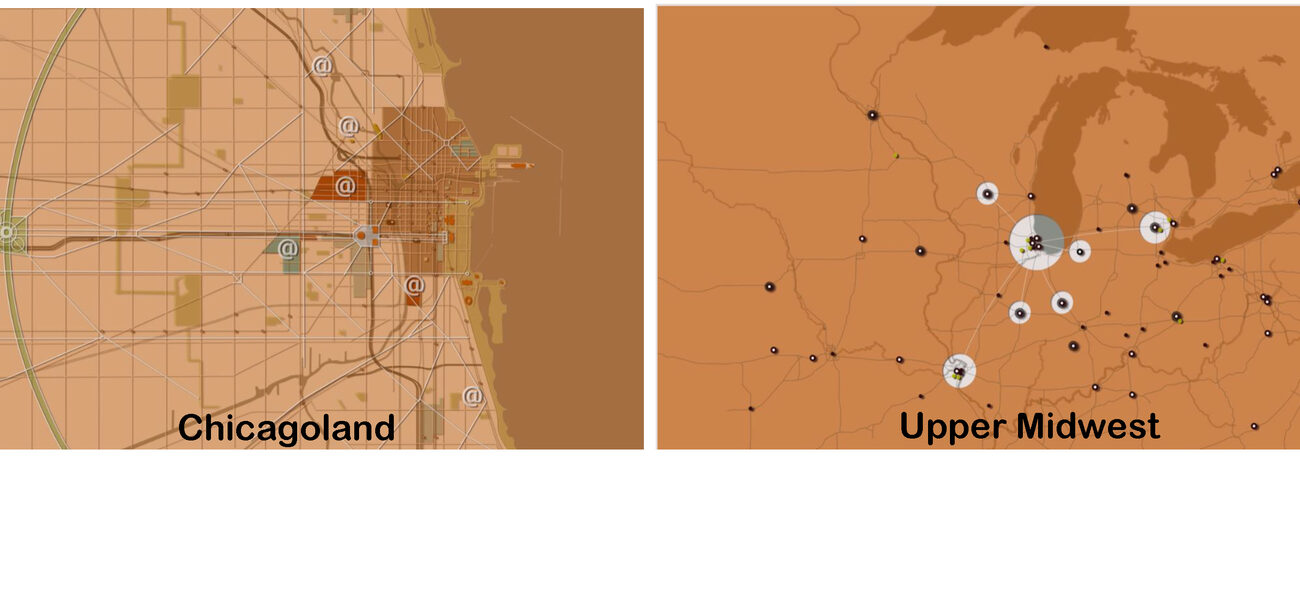

Last year, Glaser held discussions with various stakeholders in Chicago to explore the possibility of creating a regional hub-and-spoke, subscription real estate network for a consortium of Midwest universities. The 12-square-mile map of Chicago Loop today is extraordinary, as it encompasses dozens of institutional anchors and tens of thousands of full-time students, sometimes earning it the nickname America’s Ultimate College Town. How might the Chicago academic ecosystem grow in the future? Tapping Campus 2.0 strategies, the City could leverage reciprocal relations to dozens of other Midwestern college towns to become a regional “threshold to the global economy” for dozens of anchors, like the University of Indiana, Notre Dame, and Purdue.

Several notable institutions are already reaching beyond their immediate geographic constraints in a similar fashion, setting up remote campuses to position their faculty and alumni in global markets. Two examples: Cornell Tech, adjacent to Manhattan, is a joint academic venture between Cornell University and the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology; and the Los Angeles expansion of ASU’s Cronkite School of Journalism into the soon-to-be-refurbished, Julia Morgan-designed headquarters of the defunct Herald Examiner newspaper. Announced in August 2018, the project will be accompanied by private development that will revitalize the neighborhood, including hotels, restaurants, and retail shops. Both these developments offer examples of potential Campus 2.0 strategies that hundreds of anchors can employ going forward.

As a way of bringing several university talentsheds together to compound their opportunities for innovation, Glaser suggests the creation of what amounts to the academic equivalent of athletic conferences, where peer institutions share operational expenses, profits, administration, and the value of being part of a prestigious, iconic group.

“Why can’t we do this academically, gathering Tier 1 and 2 students together, creating a national, even global network of places to create an integrated network?” he proposes. “My experience working with startups shows that people don’t work in a single place. The nature of their work is cooperative, so it takes them all over. For example, someone based in Bloomington, Ind., could spend two months working with a group in Chicago, but not have to choose one ecosystem over the other.”

In the Campus 2.0 world, universities need to identify if they are either hubs or spokes, or perhaps a combination of the two, depending on the populations they serve. It’s possible that consolidations or mergers will ensue, not in the way large companies buy smaller ones, but rather in associations that build on their combined strengths, such as expertise in a particular field or a better geographic position.

“If universities can converge their talentsheds, tap into emerging shared workplace, and brand the resulting networks as extensions of their academic missions, it could really be quite powerful. Partnerships are the key to the future of education,” he concludes.

By Nicole Zaro Stahl