Before Covid, many institutions talked about delivering education online but most pursued it only to a limited extent. Then came the pandemic, which “sent the entire globe into this online experiment, like it or not,” says Jay Deshmukh, associate principal for Arcadis’ IBI Group in Toronto. Curious about how taking space out of the equation was affecting higher education, she began interviewing a few professors “about how they were doing with this sudden flip of a switch that put them in virtual land.” Those calls led to other calls, which evolved into a three-year global research project in which she interviewed over 250 students, professors, and space planners. The good news: 18- to 24-year-old students really missed being on campus and are glad to be back. The bad news: They have changed; the institutions have changed; and campuses don’t quite fit anyone’s needs anymore.

One day early on in the COVID lockdown, Deshmukh found herself working at home, preparing to give a virtual presentation to 50 people in Ottawa, while her ninth-grade son struggled to adapt to online education, and it occurred to her that people everywhere were facing this same struggle. That realization set in motion her research into what happens to higher education “when we take space out of the equation?”

The 30- to 90-minute interviews—about life, education, and research before, during, and after exile from 100-plus campuses around the world—gave Deshmukh a very nuanced sense of how virtual learning was affecting the higher education community, particularly in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Ultimately, she says, they gave her a good grasp of how those long, isolated years changed teaching, learning, and other work for students, faculty, and administrators, and most importantly, how those changes affected their architectural needs and preferences today.

After three years of ongoing interviews during and after the pandemic, she distilled 10 insights about the future of campus design:

- Each institution/faculty will define “hybrid” specifically.

- Peer and independent learning will grow.

- ‘Think and do’ spaces will take center stage.

- Everything everywhere, all at once – the future will be in person and online, here and abroad.

- Boundaries between campus and community should be reconsidered.

- The campus will be a key culture-generator and social gathering place.

- Offices have changed.

- Student experience matters.

- Place matters.

- Reputation matters. Expectations matter.

A Flattened Education

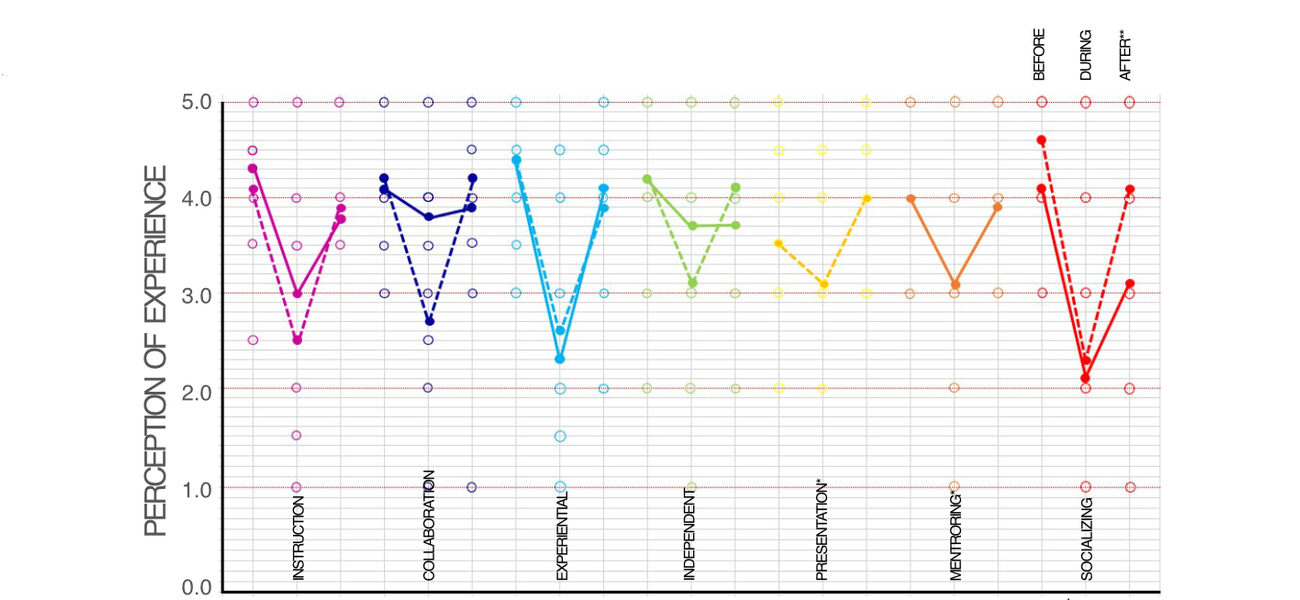

Most students and professors Deshmukh interviewed felt the virtual life had affected seven crucial aspects of higher education: Instruction, collaboration, experiential learning, independent learning, presentation-giving, mentoring, and socializing.

Of these seven modalities, only presentation-giving improved by the end of the pandemic, probably because Zoom is less intimidating for shy people. “I’m not very good at public speaking, and having notes onscreen and recording myself really helped with preparation rather than trying to wing it,” explained one student.

Of course, the global online learning experiment had other benefits. Older students value the flexibility, and some faculty like the new options it gave them, enabling them to expose their students to giants of their field, people they would normally never have dreamed of inviting to speak. A few schools, like the Savannah College of Art and Design, grew their international enrollment thanks to their online offerings.

But both faculty and students agree that in most ways, education suffered in the virtual world. Experiential learning was particularly hard-hit. “I know they tried, but virtual labs were just plain boring, and learning anything real was nearly impossible,” recalled one student.

When it came to studying, one professor complained that students “lost their capacity to be students, lost their sense of curiosity and of being engaged and collaborative.” Motivation was often a problem. “There were big fluctuations in my focus at home; sometimes I was very motivated; other times I was distracted, with brain fog,” said one student.

Socializing was also difficult for students. “Socialization wasn’t really possible …Whatever ‘friends’ I made, I knew their names and three things about them. Now it’s a lot better, and one has a sense of finding commonalities and forming community,” said one student.

Mentoring didn’t slip too far, but some professors questioned the depth of the online relationship.

Overall, traditional students (18- 24-year-olds), had the hardest time adjusting to online education. One student told Deshmukh he “missed the friends he had not yet made.” Those students who managed to build a circle of friends anyway fared best. “The students who did well were the ones who managed to create some kind of social space that allowed them to stay engaged as students,” she says.

Now that lockdowns are behind us—at least for now—satisfaction is nearly up to pre-pandemic levels for both students and faculty, with one exception: While student satisfaction with the social side of campus life has bounced back sharply, professors have mixed feelings about it.

For many professors, the habit of working from home has reduced chance encounters with colleagues. Many said they don’t feel they are back at school yet. “When some people decide that they will be here on Monday and Tuesday, and somebody else is here on Wednesday and Thursday, their relationships aren’t the same as they were before,” says Deshmukh.

Many told her that when they go to their department, they hardly see anyone, so they are staying home more. “Everyone is waiting for the other to bring that life back,” she says.

Some scholars found this depressing. They told her, “In pre-pandemic times, you were guaranteed that if you did a lunchtime presentation, that hall would be full, people would be there in the doorways, out of curiosity and to support you…now I can get barely half a roomful, and that makes you feel dejected.”

The Third Teacher

Educational facilities designers often talk about the physical environment as the third teacher, according to Deshmukh, and her research generally supports that view.

Many students Deshmukh interviewed said they found the lack of a shared physical space made learning more difficult. A third-year student at Cambridge University told her that she can’t remember anything she learned her first year. “There were no hooks,” is the way she put it.

The Cambridge student wasn’t alone in feeling that somehow the lessons hadn’t stuck. Many students Deshmukh interviewed complained of the same thing. “Our brains take in a lot of environmental cues to situate and retain information,” says Deshmukh.

Despite the mixed results of the global experiment, Deshmukh believes there is no going back to 2019. She argues that hybrid education is here to stay for a number of reasons, including the rise of distance education, new learning structures, and ‘flipped classroom’ models in which students learn information online then discuss it in person. This will lead to changes in the way campuses are used, she says, but exactly what those changes are will depend on the school.

In addition, professors told her, students have changed since the pandemic. Some are not performing at the level they should be as college students, for example. But more importantly, in Deshmukh’s view, the students’ life experiences are now very different. After several years of having to take more personal responsibility for their education, students are pursuing it now in a more entrepreneurial way.

Be True to Your [2024] School

Instead of resisting the preferences of today’s students, Deshmukh believes campus planners should adapt to them. Space planning and design strategies need to be people-driven, not space-driven: “We can’t be rolling out our pre-pandemic space standards from one building to the next and just hope for success,” she says.

Her research led her to ten conclusions about how campus designs need to change to meet future needs, including these three takeaways:

Focus on what your students missed most.

“Think about what is it that is generating the culture,” says Deshmukh. “Every one of us is dealing with a campus that has a unique culture. There is an ethos to your campus that is precious, that is unique, and that creates the culture and the social stamp.”

Architecture is often an important part of what creates that unique identity. “In terms of uniqueness, oftentimes students would talk about beauty, which kind of surprised me,” says Deshmukh. “Especially right in the beginning, they said, ‘My campus is so beautiful in the spring, and I really missed it.’ Somebody else would say something about the architecture.”

Build More Small Collaborative Spaces.

“Students have now had a taste of agency,” says Deshmukh, and they have “a greater desire to be entrepreneurial, to find their own pathways through education.” Many students said they want more opportunity to learn from their peers, a wish that is likely to translate into greater demand for places where small groups can work.

More small working spaces might not sound hard to create, but Deshmukh says it will require some innovative design. Acoustics, for example, will be a challenge: “To be able to allow things to occur side by side, without one impinging on the other, is very important.”

Create Spaces That Pull People Together.

Deshmukh advises focusing on “sticky spaces”—places on campus that deepen students’ sense of engagement and belonging—and look for ways make them more welcoming.

At Algoma University at Sault-Ste. Marie, a northern Ontario institution with a First Nations heritage, Arcadis-IBI redesigned a popular student pub to incorporate Indigenous design forms, which made it more popular. More recently, a similarly themed second student-gathering space called “The Nest” has also garnered the interest of students, faculty, and community partners.

“What was seen as a very social space, suddenly, because it was available, because it was unique, because it had a palpable energy, people are now having meetings in there. It was never actually planned for that, but once you have a space that genuinely pulls people together, it starts getting used for a lot more than what you might think of,” says Deshmukh.

Make It Flexible—With Forethought.

Solutions are available that make it possible to configure rooms in very different ways. But designers can still add value in these flexible spaces. Stanford Design School, for example, includes diagrams in its flexible learning space, making it easier for people to adapt it to their needs: “Here’s how the room can be set up. You don’t have to try it out—I’ve already done it.”

Ultimately, flexibility needs to begin with the planner. “Many times, architects, myself included, have actually believed that previous knowledge and established standards are the most important part of what we bring to the table,” says Deshmukh. “But today, you also need to be able to question those standards and experiment with people to come up with an original solution that aligns with this new, hybrid environment of education.”

By Bennett Voyles