The design and planning of medical and health sciences education facilities serve as both the precursor and the wave of the future, with facilities that are not only mixed-use, but truly hybridized and integrated. Formerly siloed programs for nursing, medical, surgical, and pharmaceutical training reap exponential benefits from shared technology, resources, and spaces that enable multiple institutions and stakeholders to offer more robust programs. The hybrid building model mirrors a coevolving approach to healthcare, where teamwork is central, and training with the latest technologies is key. By accommodating the functions of multiple disciplines, forward-thinking institutions can both leverage available space and focus on creating environments for the interpersonal collaboration that underpins the experience of 21st-century health practitioners, as well as that of their patients.

“As we’re moving into hybridization of our work, our transit, and even our intelligence with the emergence of AI, we should examine how that is playing out in the built environment,” says Jonathan Kanda, principal with CO Architects’ Los Angeles practice.

Past as Pretext

Hybrid-program designs gained momentum about 15 years ago and have remained a steady fixture in medical education. “Buildings with multiple users, or even multiple institutions coming together under one roof, have been holding steady at about 50% of our projects across the medical education board,” says Benjamin Bye, senior associate with CO Architects. “We view this as a trend that is here to stay.”

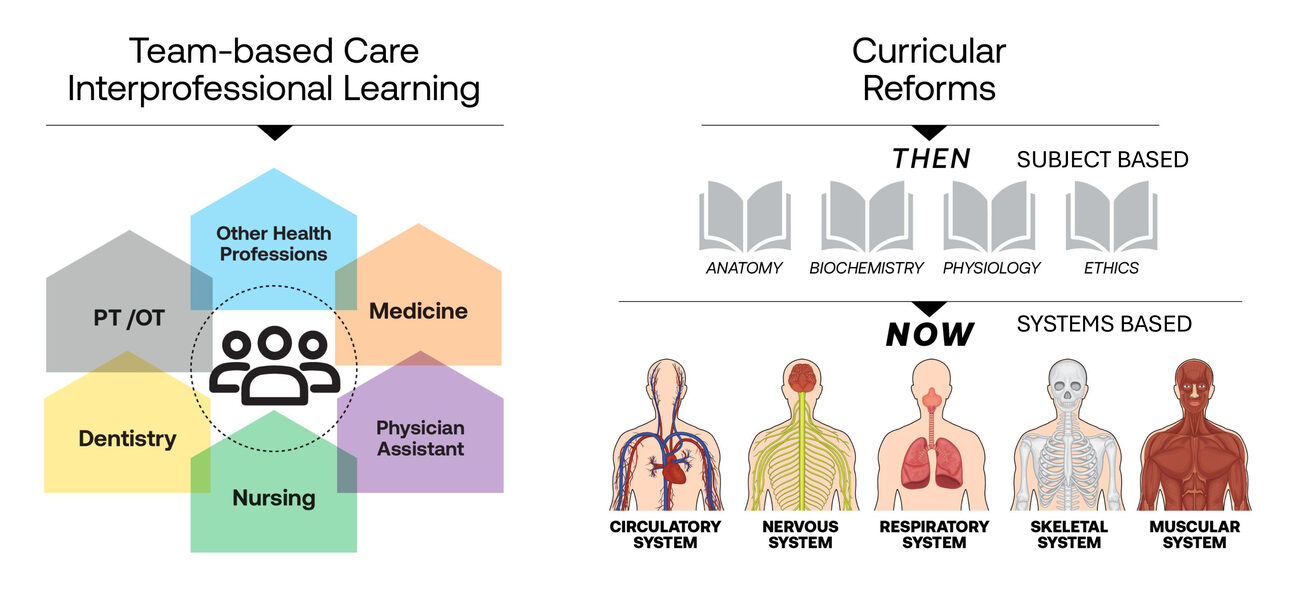

The move toward hybridization has been driven by several factors, including a mandate from the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), which emphasizes team-based care and interprofesional training. Additionally, a shift from subject- to systems-based curricula has been informed by calls to increase medical school class sizes and address healthcare shortages in cities that lack medical schools, which can result in a “maldistribution” of care providers that can often be addressed with the introduction of a start-up medical school.

The hybridization trend has accelerated in the last five years, with two-thirds of recent medical school projects being built separately from existing university or medical center campuses. “These are urban typology projects that stand alone in an urban context,” says Bye.

As curricula have shifted from subject-based to systems-based learning, new types of spaces within buildings have also emerged. At the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, a “superfloor” integrates standardized patient exam rooms, mannequin-based simulations, and virtual anatomy into a single space, while at the University of Edinburgh, a “skills loft” combines labs and communal spaces in a double-height environment. Versatile spaces like the “forum” are designed to accommodate activities ranging from lectures and ceremonies to informal student gatherings, replacing traditional auditoriums. Meanwhile traditional teaching labs are being replaced by virtual and plastinated anatomy spaces; and “simulation decks,” which merge patient care scenarios with a black-box theater concept, allow for flexible, real-world reenactments.

An Emerging Example

A 700,000-sf building is under construction in Charlotte, North Carolina’s Pearl Innovation District. This building will house medical and health sciences programs from multiple institutions, an advanced surgical training center, and industry partnership space to support and create a “knowledge community.”

For this complex program with three users, “We started by exploring various organizational models, from highly segmented departments to fully integrated spaces, ultimately landing on a hybrid approach,” says Scott Kelsey, principal with CO Architects.This model allows each institution to maintain its identity while encouraging shared use of classrooms, social areas, and simulation spaces, with some 60-80% of the facility dedicated to shared spaces.

A key feature of the building is its emphasis on community and social interaction. The lower levels are designed with open, flexible spaces, including a forum that replaces the traditional auditorium with a flat-floor, living-room-style community space, complemented by learning studios that can be reconfigured to accommodate different group sizes, and high-tech simulation rooms for surgical training. In addition to educational spaces, the building includes lounges, study areas, and fitness facilities. This layout promotes the sharing of experiential programs among institutions, enhancing the District’s role as a medical education and knowledge-community hub in a large city that previously lacked one.

Differing Stakeholder Models

When multiple institutions share a hybrid building, ownership and management can vary. In developer-owned buildings, each tenant leases their own space, while shared areas are managed collectively. In cases where each group has its own financial stake, however, aligning different institutional cultures and navigating funding disparities requires collaboration, resource-sharing, and careful negotiation; strong institutional relationships are key.

The Collaborative Life Sciences Building in Portland, Ore., is owned and occupied primarily by a triumvirate encompassing Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and Portland State and Oregon State universities. As the lead partner, OHSU manages the building; however, a memorandum of understanding outlines each institution’s responsibilities, including space management and maintenance. The building spans 650,000 sf, making it one of the largest hybrid facilities of its kind. “One key takeaway about these hybrid facilities is that they are inherently larger buildings than we have seen in the past, since they are bringing together the needs of multiple stakeholders,” says Kanda.

About a third of the facility’s space is dedicated to research, with a further 20% for clinical activities (such as dental school programs) and the remaining 40% for educational functions. Many large classrooms, research labs, and simulation areas are shared among the three stakeholder institutions.

“But not everything is shareable,” explains Kelsey. “You also have spaces that are specific to a discipline, such as the dental school or inpatient nursing bed labs, that have to remain more specialized due to patient flow or pedagogy.” Shared social and study spaces are scattered throughout, however, serving around 800 students daily. To further encourage interaction among the various users, the design features a central “mixing bowl” atrium at the building’s heart.

Over the years, OHSU has served as a catalyst for surrounding development along the Portland waterfront. Tying into this urban fabric, the Collaborative Life Sciences Building’s layout emphasizes connectivity both within the facility and outward, being accessible via mass transit, bicycle, and car. Kanda notes that, “Once an institution makes a commitment in an emerging area, it creates long-term civic and developmental confidence. Like-minded programs begin to aggregate around the institutional ‘keystone,’ and then housing, food, and entertainment in the surrounding area take root.”

A “Practice-Ready Precinct”

Designed to serve multiple programs within one institution, the University of Kansas Medical Center’s new 170,000-sf, state-funded hybrid facility houses medical and health science programs, as well as continuing education for healthcare professionals.

The planning process focused on shared spaces, with representatives from nursing, medicine, and allied health coming together to discuss space needs. “The different schools have different class and program sizes,” says Bye, “and sometimes they all want to be together at the same time. So scalable space was very important.” Nearly two-thirds of the building is dedicated to collaborative use, with classrooms, simulation training environments, and community spaces encouraging interaction across disciplines. An unusual feature of the design is the absence of administrative offices, fostering a shared core facility that prioritizes education and competency training.

The concept of hybridity extends beyond the building to the precinct level, blending research, education, and clinical activities within a unified “practice-ready precinct” that is connected to the broader campus through a bridgeway that also serves as a key social space.

Architectural Identity and Community Anchor

Traditionally, university buildings, particularly those tied to historical institutions, reflected a strong brand identity. However, as more hybrid buildings emerge in urban settings, there’s a shift toward creating an identity rooted in the local environment and context.

“Institutions are more interested—and interested earlier in the process—in the architectural identity of the design,” notes Kanda. “They want a rich story that bridges the idea of ‘their space’ to the idea of better health for their region.”

For instance, the Health Sciences Education Building in Phoenix draws its façade inspiration from the sandstone canyons surrounding the city, reflecting both the region’s natural beauty and its climatic conditions. Similarly, the Collaborative Life Sciences Building in Portland takes cues from the Willamette River’s shipbuilding history, blending the area’s industrial past with the building’s modern design. The University of Arizona’s Health Sciences Innovation Building, meanwhile, evokes the iconic saguaro cactus in both the building’s design and its public spaces.

By blending environmental, historical, and cultural influences, these buildings forge a new kind of identity that connects the institution to its community and surroundings, creating a sense of place that goes beyond branding. Moreover, by integrating medical schools into communities that need them most, these projects are poised to create lasting social and economic impact, offering a model for future healthcare and educational growth.

By Liz Batchelder