In the span of 16 months, Seattle’s Fred Hutch Cancer Center formulated and implemented a space realignment initiative that divested 30,000 sf of leased space, generated $2 million in savings and another $2 million in cost avoidance, and impacted approximately 1,400 people, 20% of its 7,000-member workforce.

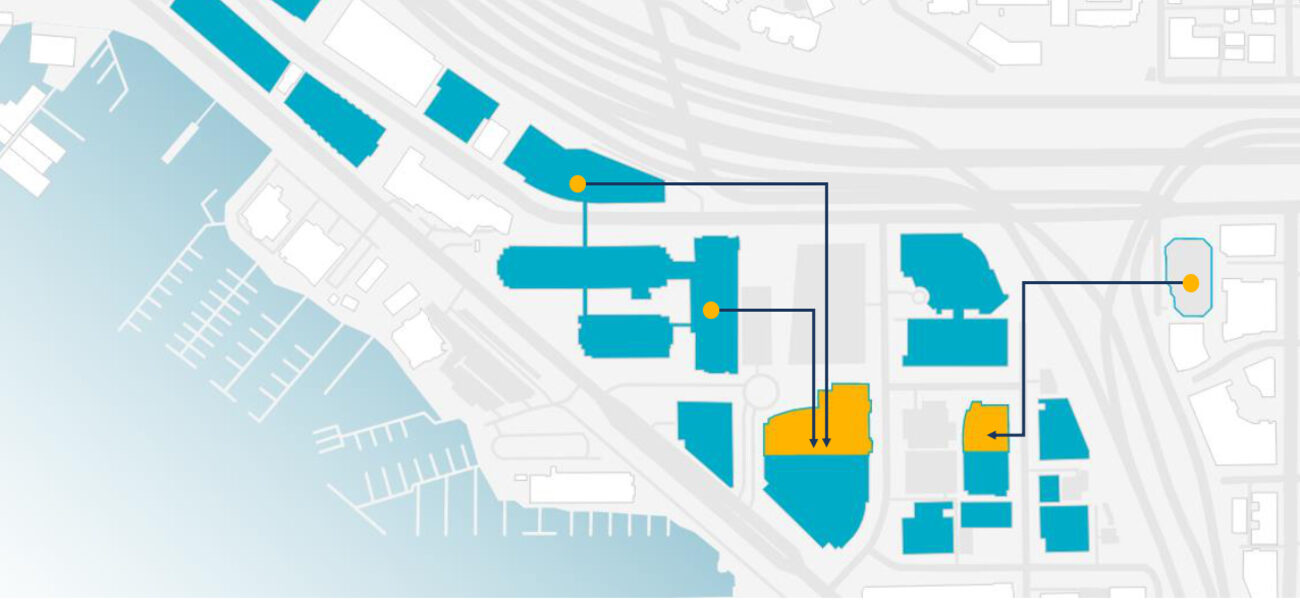

After roughly a year of planning that included a carefully calibrated communication effort, the institution’s real estate group spent July to October 2023 overseeing 37 moves across 31 departments, taking people out of three buildings, one of them leased, and putting them into two buildings with underutilized space. The process created 243 new workstations for hybrid and remote workers and freed two floors of two different campus buildings for conversion to research labs.

“Fred Hutch is driven by our mission of preventing and eliminating cancer and infectious disease,” says Natasha Adams, the organization’s director of Real Estate. “The more wet lab space we have, the closer we are to the cure.”

“Every dollar saved on a lease can be spent on something more important to our mission,” adds colleague Delaney Vavra, senior manager of Space Planning & Data.

Building the Framework

Retaining the flexibility of its pandemic-inspired work-from-home policy had left Fred Hutch with a significant amount of underutilized space. A survey conducted in mid-2022 revealed that 50% of the organization’s 7,000 employees planned to come on site only two days or fewer per week. With the goals of adding more wet labs and exiting underutilized leased offices, the real estate group was charged with crafting a more efficient space utilization plan.

For Vavra and Adams, part of the preparation for such a wide-ranging initiative included attending a Tradeline Space Strategies conference in October 2022 to learn how other organizations were handling seat assignments for hybrid and remote workers. Among their questions: How common was the assigned-seat model? What level of on-site presence merited an assigned seat? Could a different approach be more effective, for instance, allocating square footage instead of seats to a department?

Building on this experience, the planners developed a framework for the new policy, supported by 12 weeks of badging data from the various teams. Specific seats are assigned only to individuals on site at least three days a week. Employees on campus less frequently—whether hybrid (defined as less than three days per week) or remote (less than one day per week)—are given use of either a hotel seat or a just-in-time (JIT) seat. The only difference between these two is that hotel seats are reserved, and JITs are drop-in, according to the wishes of individual departments. There is no physical distinction.

The office space under consideration was sorted into three categories, formally defined and prioritized as follows:

- A private office, prioritized for executive leadership and faculty, is defined as an enclosed workspace with a door and one desk, but no mandate for an exterior window.

- A shared office, prioritized for directors, is an enclosed workspace with a door and two or more desks, again with no mandate for an exterior window.

- The open workstations or cubicles, for all other workforce members, consist of a desk in an open office environment. They may or may not be partitioned from neighboring workspaces.

The framework included two additional provisions judged key to success. First, the seat allocation scheme had to apply to all members of the Fred Hutch workforce, whether employee, non-employee, faculty, physician, or executive. “It was extremely important to get leadership buy-in on this,” says Vavra. Without the universal standard, “we would always have questions about equitability between some categories and other staff. And we knew we wouldn’t meet our goal of making better use of our office space.”

The other issue was private office eligibility. For those on site three days or more per week, space type is prioritized based on job title. Private offices are prioritized for vice presidents, executives, faculty, and physicians.

Announcing the Changes

The next step was determining where and how to start implementation. Instead of tackling the entire campus at once, the team made the choice to limit the initial effort, targeting what aligned with strategic initiatives: the two floors suitable for lab conversions and the building with the approaching lease expiration.

“We could have done more, but we chose not to,” says Adams. “We also did not want to notify people to vacate their assigned space until necessary. If we don’t need the space yet, we’re not knocking on doors saying, ‘Take all your stuff home.’”

Presented to the COO in January 2023, the revamped space allocation policy was then ready for a carefully choreographed roll-out to the various levels of the organizational hierarchy. It started with a series of 30-minute, one-on-one meetings with executives during February and March, explaining upcoming changes and listening attentively to feedback. Several meetings had follow-up discussions to address leaders’ concerns in greater detail. Pain points were approached with the aim of negotiating a solution, rather than standing as an obstacle or lapsing into an impasse. Emphasizing the “why” behind the changes—the best use of resources to support the Fred Hutch mission—helped the planners secure agreement from the executives and get them on board.

Meetings with the entire executive team were held in late March and mid-April, followed by a managers’ forum at the end of April and culminating in the organization’s town hall meeting in mid-May. By that time, those impacted had been notified of the changes. The institution-wide gathering had the larger purpose of introducing the new space plan to the entire workforce, explaining the rationale behind the move sequencing, and providing the opportunity for questions. It also laid the groundwork for the multiple phases to follow.

Change Management Strategies

The planning team employed several tools to ensure buy-in across all levels of the organization. One was developing a consistent message throughout all communications.

“My vice president and I delivered the exact same canned presentation, starting with our COO, who was the enforcer of the change,” says Vavra. “Moments of trust were built when the audience that we had just presented to heard us repeat the same information to the next audience. It was confidence-building that we weren’t changing our messaging as we changed our audiences.”

Another very helpful protocol was asking each executive to assign a departmental point of contact to work with the real estate group on the project. This was an important role, not just to coordinate the project execution, but especially the actual moving. The liaison was also key in communicating the changes to the various work groups.

“Studies have shown that people don’t like hearing their team is moving or shrinking space from facilities folks,” says Vavra. “They want to hear it from their own manager. This was a very successful format for us, and we’ve repeated it in other projects.”

Flexibility and Sensitivity

Throughout the process, the planning team was sensitive to work group needs and situations. For example, when a discrepancy surfaced between an employee’s badging data and self-reported occupancy, they reached out to find out why. Learning that the absence was due to extenuating circumstances and an on-site return was imminent, the person was assigned a designated seat.

“My team has had many similar conversations, and every single time, they end up slightly differently,” says Vavra. “But the framework of our space allocation policy has given us a good starting base for all the conversations or negotiations.”

Vavra and Adams highlight four components of their change management plan that helped shape its acceptance.

- Have a saleable ‘why.’ “Planners need to know what problem they are trying to solve,” they advise. “We in facilities are not asking our partners and our teams to change how they’re working. We’re asking them to acknowledge that how they’re working can be done in less space, or it can be done in a different physical location when they are on site.”

- Plan your communications in advance so you know who you are talking to and when. “We have multiple answers to every one of the ‘why’ questions someone might ask, like ‘Why us? Why now? Why here?’ If you can’t answer those questions, the communication will not be successful.”

- Give choice when you can. Even a little bit of autonomy, like the choice between hotel or JIT seats, helps people feel more ownership over their approach to space.

- Don’t sugar-coat it. “Moving isn’t easy,” notes Vavra. “Set the expectation up front that moving isn’t fun, and explain that you’re there for the hard changes.”

What’s Next

With the success of this first implementation confirmed, Fred Hutch has embarked on a longer- range space realignment plan. The next chapter is much more complex: swapping the administrative building with the clinic faculty building. The first of the 20 phased moves started in late February 2025, with the remaining 19 expected to run until May 2026.

“We used the same process,” says Vavra. “I think it is working well for us.”

By Nicole Zaro Stahl