In a higher education landscape facing shifting enrollment trends, rising costs, and an uncertain future, institutions must rethink how they use their physical spaces—not just as real estate, but as engines of purpose. And rather than traditional return on investment (ROI), they should employ “Return on Mission” to evaluate their success rather than metrics like net-to-gross ratios, utilization rates, and physical occupancy to assess their spaces.

Relying solely on ROI falls short of capturing what truly matters: the activity inside the space and the value it generates, say Petar Mattioni, an architect and partner at KSS Architects, and Alexander Brown, a practice lead from Attain Partners’ product and innovation team.

The “Return on Mission” (ROM) framework introduces the concept of a flexible combination of metrics that evaluate space investments not just on financial ROI, but on how they advance the core goals of a university—whether that’s research output, student success, or community engagement.

ROM isn’t a wholesale reinvention of design or planning. “A lot of institutions are already doing parts of this,” notes Brown. “We’re helping connect the dots into a unified framework that supports long-term flexibility and strength.”

ROM is “an institution-specific metric that tracks both investment and activity’s contribution to the institution’s mission.” While that might sound complex, it’s surprisingly intuitive. “Think of it as a heat map,” says Brown. “You apply different ROM expectations to different parts of a building depending on their use.”

For Mattioni, this new framework closes a historic gap in architectural design. Instead of waiting until post-occupancy studies are complete to analyze success, ROM proposes defining them up front. “What kind of research do we expect to happen in this building? What’s the density of activity we want to see? Let’s build those expectations into the design itself.”

Adaptive Architecture at Penn: ROM in Action

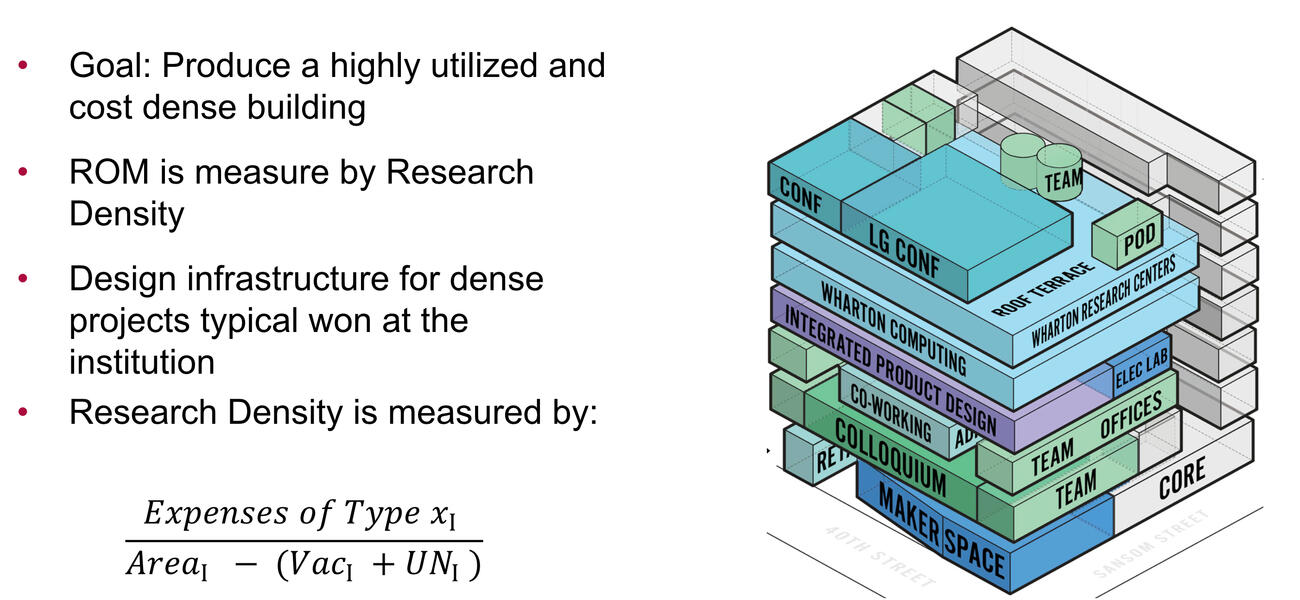

The ROM approach is illustrated in three recent projects at the University of Pennsylvania. The first is the new Amy Gutmann Hall—a 120,000-sf, six-story, mass timber data science facility. Designed by Lake|Flato and KSS, the building is notable not just for its modularity and sustainability, but for how clearly its programs are zoned: Nearly 50% of the building is dedicated to research centers, while academic and student support functions make up the rest.

The design boasts structural clarity: “We have a central spine that distributes all mechanical systems and public circulation,” says Mattioni. “Program zones are clearly divided left and right, and vertically as well.”

But beyond architectural efficiency, the true innovation is in how this layout ties back to ROM. “For this particular project, we might measure ROM through research density,” explains Brown. “That means looking not only at construction cost, but at research expenditures per square foot.”

Brown emphasized that this isn’t about squeezing productivity out of buildings, but aligning design with institutional intent. “You can take any metric—cost per credit hour, utilization rate, research output—and tie it back to your programming decisions,” he said. “Under this model, we’re not assessing, after the fact, whether a building is working. We’re designing toward a measurable goal.”

Another example at Penn is Tangen Hall, home to Penn’s Venture Lab, a building that sits at the nexus of business, design, and engineering disciplines. It’s a sleek, 70,000-sf facility situated in Center City, Pa., jointly serving the Wharton School (the business school), Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science, and Penn Design’s Integrated Product Design Program.

“The way this building is envisioned is as a toolbox for the university,” says Mattioni. “It’s designed to support ventures, from conception to launch.” With a 64% net-to-gross efficiency and capacity for around 1,400 occupants, the Venture Lab is structured for agility, with plug-and-play zones, exposed ceilings, and a service core that enables flexibility over time. This layout encourages a rotating cast of ventures—300 annually, of which about 2% mature into startups, according to Wharton.

“The core is fixed,” explains Mattioni, “but everything from the core to the left is adaptable. No ceilings, all the utilities are above, programs can move in and out.” Design and planning decisions needed to be mapped to the building’s mission—innovation—with program-specific expectations depending on space type. “A dry lab doing product development will yield different density than a clinical research space.”

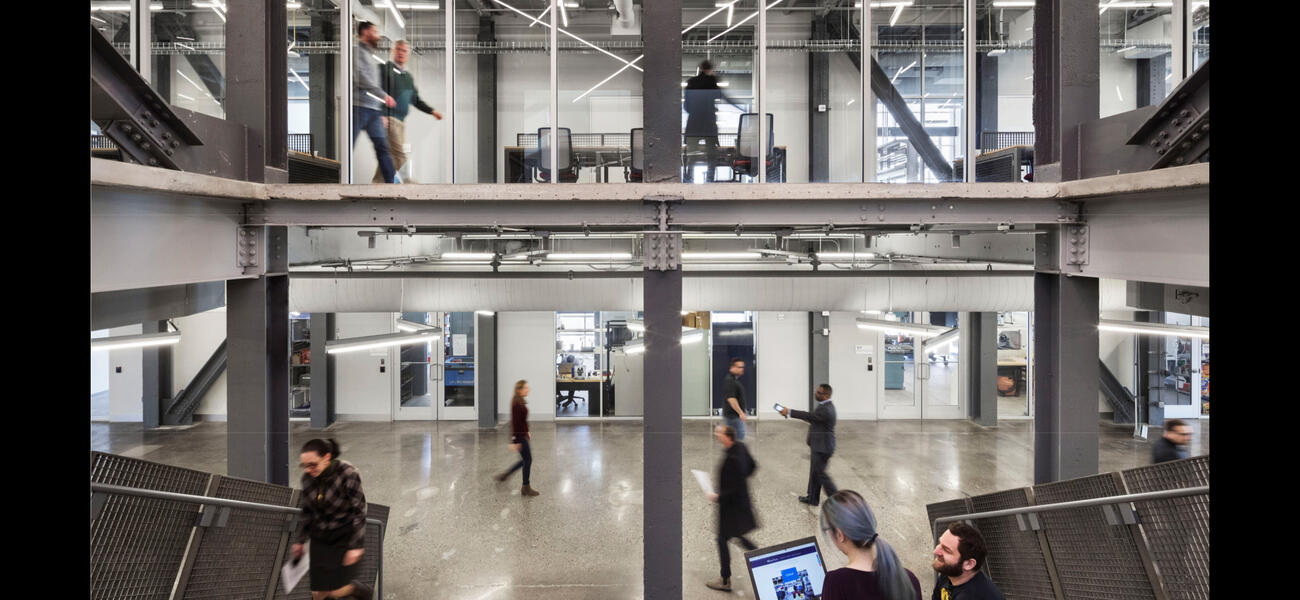

Just across the Schuylkill River, the Pennovation Center tells a different story. A hybrid of retrofit and new construction, this 69,000-sf project anchors Penn’s eastward expansion, and was designed by KSS, in the role of program lead, in collaboration with HWKN as the design architect. Opened in 2016, the center supports engineering startups and growing ventures—often ones that first emerged at Tangen Hall.

“This project began with a 23-acre industrial site. We took an old building and added on to it, organizing the new and old around a modular concrete grid,” says Mattioni. Inside, there’s a careful choreography of spaces: wet labs on the second floor, convertible dry labs on the ground level, and shared amenities strategically located in the new addition. The modular layout positions labs around the perimeter to maximize daylight, with denser, shared functions in the center.

Importantly, this layout also supports a key element of the building’s ROM—community. “By removing functions like autoclaves and tissue culture rooms from individual labs and making them shared, we encouraged interaction,” says Mattioni. ROM analysis here required nuance: “This isn’t a brand-new, unified building,” Brown emphasized. “So instead of segmenting by floor, we used clustering. If a faculty member’s labs are stacked or spread out, we group them by activity, not geography.” This allows Penn to assess not only how the building performs in parts, but how its flexible infrastructure supports long-term institutional goals like entrepreneurship and tech transfer.

A Living Lab for Research and Resilience: ROM at Rowan University’s Discovery Hall

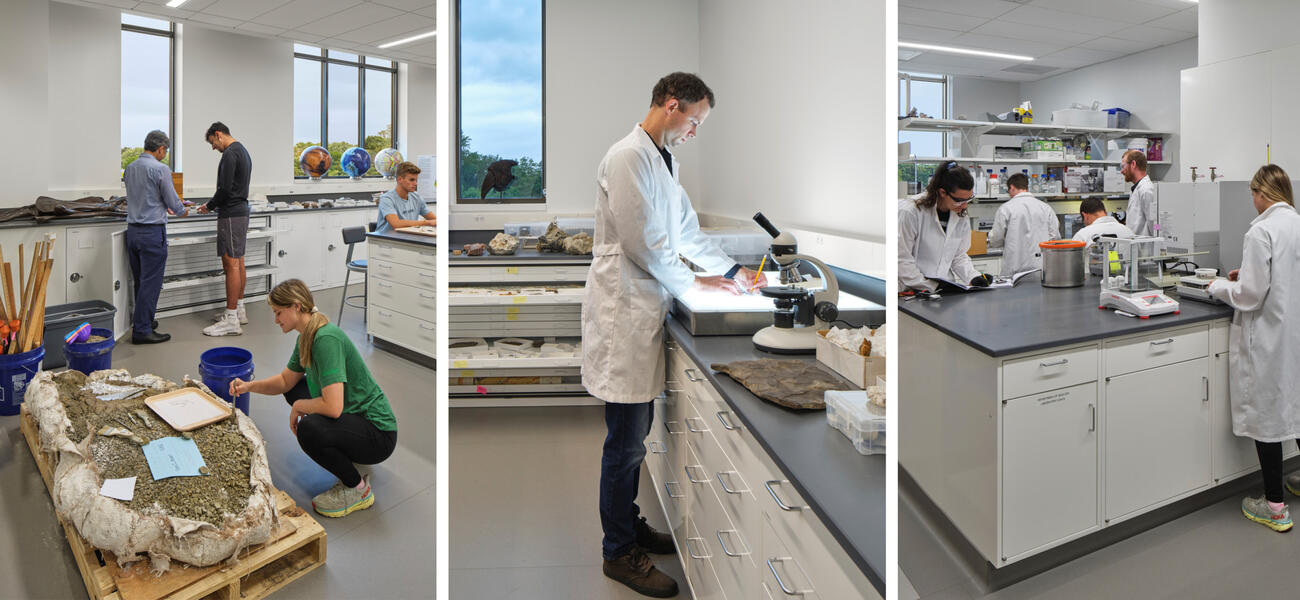

In southern New Jersey, Rowan University is reshaping what it means to be a modern research institution—starting with its buildings. At the heart of this transformation is the new 67,000-sf Discovery Hall.

Built as the gateway to Rowan’s east campus, Discovery Hall symbolizes a pivotal moment in the university’s shift from a primarily academic model to one with a strong practical research emphasis. Anchored by the School of Earth and Environment and the Department of Geology, the building is organized around a central spine—which Mattioni calls its “main street”—that runs through the core. Flanking this thoroughfare are paired lab zones and stacked classrooms, designed to create flow, flexibility, and a high degree of functional clustering.

“This kind of spatial logic makes adaptation easier,” says Mattioni. Indeed, the building’s story didn’t stop when construction ended. In fact, much of its identity has taken shape post-occupancy. “Most of the faculty who now occupy Discovery Hall weren’t even hired when it was being designed,” notes Brown. “That’s not unusual. But what’s impressive is how Rowan adapted.”

One standout is the building’s rock-processing facility, for which the university transformed oversized janitorial closets and underutilized storage areas into fully functional, high-density research space. What could have remained idle corners instead exemplify innovation—labs with real geological purpose, humming with student activity and research momentum.

Mission Math, Without the Headache

ROM is not just a planning tool, it’s an operational philosophy—a means for institutions to think about their space before the ribbon is cut.

“We’re not just evaluating design performance anymore,” says Brown. “We’re evaluating building resilience. How do you measure whether a space is still serving the mission a year in? Two years? Ten?”

Brown breaks it down using four guiding principles: clarity, simplicity, coverage, and objectivity. “You want leadership to understand these metrics without needing a deep dive into analytics,” he says. “They need to be easy to calculate and maintain. If you can’t keep a metric up to date, it’s not useful.”

He is particularly enthusiastic about “delegable metrics,” the kind that individual departments or teams can actively manage. “Think of them as levers anyone can pull to improve outcomes. Pair them with integrated metrics—composite numbers drawn from a few critical indicators—and you get a powerful narrative about how a building, or an entire campus, is performing against its goals.”

“We say all the time, ‘The building will do this, the building will do that,’ says Mattioni. “But how do you know if it actually delivers? These metrics give us a way to prove it out ahead of time.”

Brown emphasizes that institutions don’t need to be afraid of the math. “You can aggregate and standardize different types of data—utilization rates, square footage ratios, density measures. None of it needs to be calculus.” But by looking at ROM instead of pure utilization figures, universities can get their priorities straight before they begin to renovate or assign spending for a new building.

Beyond the Building: Making the Case Campus-Wide

ROM isn’t just for new facilities. “Asset optimization—understanding how to use what you already have—is critical,” says Mattioni.

ROM thinking is especially valuable when applied at the campus scale. “You could apply this to a building, but it could also be scaled up,” says Brown. For example, one client wanted help deciding who should get space in a new building. Brown’s team analyzed lab-level research density and surfaced several high-performing principal investigators (PIs) who hadn’t initially been on leadership’s radar.

By Liz Batchelder