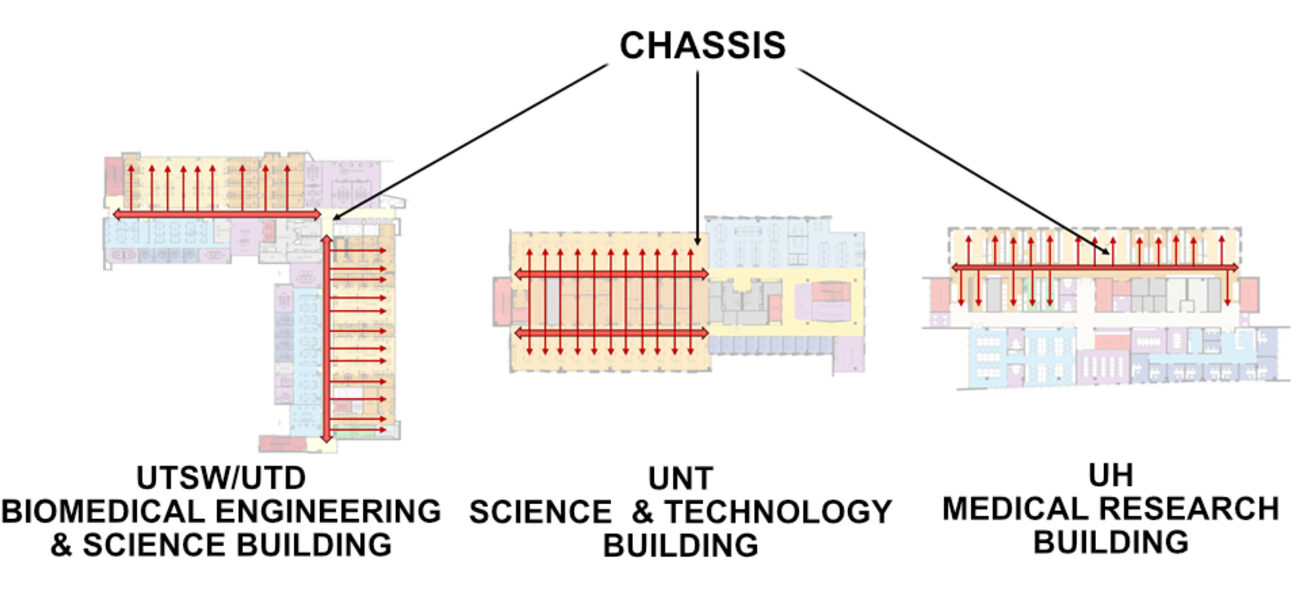

The ideal lab building can flex over time to accommodate each new generation of researchers, with minimal disruption and infrastructure change. Using an approach called the “resilient chassis,” labs are grouped by typologies and placed around a common spine or “chassis” of mechanical/electrical/plumbing (MEP) systems based on zoning and capacity needs.

The best location for each lab is determined by grouping labs together that share specialized requirements, such as vibration sensitivities, noise restrictions, lighting or electrical requirements, and instrumentation needs.

“We try to maximize shared infrastructure between different types of lab spaces, whether it is dry or wet labs, or lab support spaces, and determine how to align those to provide ease of changeability over time,” says Patrick Jones, principal at SmithGroup who leads the Science & Technology studio out of Dallas. This approach lowers the cost of future renovations and improves long-term sustainability by decreasing the volume of structural materials eventually sent to landfills.

Locating the Chassis

“It is standard practice to use laboratory modules to add flexibility of design,” says Alex Munoz, a senior laboratory planner and principal with SmithGroup out of San Diego. “We take this concept to the next level by finding a footprint to group support labs by typologies. This determines where to place the central MEP spine or spines and maximizes the utility run. Fingers from the spines can be run off into individual labs or zones instead of spanning the duct over the entire lab footprint.”

This approach avoids creating spaghetti-works above the ceilings, so systems can be easily accessed and modified during renovations, says Jones. “By using the spine approach to zone MEP distribution, we can easily cap off and serve individual labs differently in terms of positive or negative pressurizations,” he says.

“In large, multi-lab facilities, there will always be differences among labs in terms of finishes and MEP requirements,” says Jones. “In addition to finding commonalities among the labs, we also consider whether adjacent support spaces could flex in the future to become specialized lab spaces.”

What is Driving the Approach?

Other factors driving the resilient chassis approach in lab design include:

- Inaccurate pre-construction predictions of the required allocation of wet or damp labs versus dry labs: During design, a client might estimate the need for 30% dry labs and 70% wet labs, but after move-in, these ratios often evolve, requiring conversion of that lab space. While converting from wet to dry is the easier approach, it is also possible to convert from dry to wet lab space, leading to more damp space designed on day one.

- Rapid changes in emerging technologies: The pace of technology advancements can also change space allocation, including the need for additional dry space to accommodate machine learning for data analytics, artificial intelligence tools, or large automation/robotic equipment brought in to handle repetitive tasks.

- New vivarium locations: Vivarium work is now often done at the lab level rather than in the vivarium proper. This vivarium satellite, also known as “in-out space,” allows researchers to easily access support labs, increasing efficiencies and expediting research results.

- Write-up space can take a variety of forms: The location of write-up space will depend on whether PIs prefer write-up space to be inside their lab, adjacent to it, or part of a larger lab neighborhood. Keeping write-up space outside of the lab allows assistants to bring food and beverages into the space, and the neighborhood model can expedite converting the write-up space into enclosed computational space if needed in the future.

- Designing more efficient buildings increases usable space: Understanding applicable building codes and exit requirements in relation to occupancy is one strategy for increasing efficiency. “Occupants with offices and labs on the same floor can use a simple exiting strategy that uses a ghost corridor to promote more efficient circulation within the lab,” says Jones. The ghost corridor extends the usable laboratory environment and provides exit access through a portion of the lab, increasing the lab’s usable space by as much as 5%.

University of Texas Southwestern & Dallas (UTSW / UTD) Biomedical Core & Science Building

Now named the Texas Instruments Biomedical Engineering and Sciences Building, this 150,000-gsf, five-story facility opened in August 2023. The building includes lab and office space for 32 PIs from UTSW and UTD who focus on artificial intelligence, robotics, and molecular and genetic engineering. Also included is a Biodesign Center featuring a large assembly/design studio, a metal fabrication shop, and rooms for 3D printing.

“When design for this project began, there were no day-one users assigned to the facility, so it had to be highly flexible in terms of floorplates and MEP capacity,” says Munoz. “It was not until we were approximately 90% through construction documents that the school’s new bioengineering chair came in with specific lab requirements.”

He adds that since the chassis was already in place, they were able to easily tailor the labs, including converting several support spaces into core labs, such as instrument support space into a chemistry lab, and laser support space into an imaging lab.

University of North Texas (UNT) Science & Technology Building

UNT’s new 111,000-gsf Science and Technology Building will be a multidisciplinary research and teaching facility with research space for biology, biomedical engineering, chemistry, physics, computer science and engineering. Currently in construction, the project is expected to be completed in March of 2026.

“Similar to the UT project, this building had no day-one users identified during design,” says Munoz. “We only knew it would focus primarily on bioengineering labs, and that the school’s primary concern was adhering to a strict budget. To support this goal, the chassis was set and designed around the program with the proper MEP systems that would support changes as PIs began to occupy the space, at minimal or no additional cost.”

University of Houston (UH) Medical Research Building

Currently in early design, the 54,000-gsf Medical Research Building for UH, is expected to house interdisciplinary research and clinical programs focused on biology, bioengineering, computational research and emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence.

“With this project, we are moving away from the idea of designing strictly wet versus dry laboratory space, since the intended use will allow this,” says Munoz. “Instead, the facility will house only damp labs that will have the capacity to flex with each PI.” The UH project team feels this approach will help achieve budget goals and will enhance the school’s recruitment efforts with future faculty and researchers.

“There is no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to lab design, and the same is true for the resilient chassis process,” says Munoz. “It can be said, however, that applying the resilient chassis will enhance the flexibility of laboratory design both now and well into the future.”

By Amy Cammell