The 1,235-acre University of Maryland (UMD) campus in College Park sits just eight miles from the nation’s capital. Founded in 1856 as a land-grant institution, the university offers 300 degree programs through 12 colleges serving 41,000 students and—together with the University of Maryland, Baltimore—has $1.4 billion in sponsored research expenditures. Over the past decade, the school has experienced many shifts, including joining the Big Ten Conference and receiving its largest donation in university history. To keep pace, five new buildings were constructed or started during the past decade, which helped transform the campus and create a vibrant STEM district beyond the campus core, connecting students, faculty, and researchers from various disciplines.

“The campus has historically been a Georgian campus and quite homogenous in terms of its architecture. That is now changing,” says Craig Spangler, FAIA, senior principal at Ballinger. “Having five buildings constructed within a tight area of the campus on an overlapping basis allowed for complementary programming to minimize redundancies and promote the notion of interdisciplinarity.”

Cooper Robertson, in collaboration with other firms including Ballinger, recently led an update to the campus facilities plan that identified development capacity and ways to upgrade existing facilities and meet strategic and sustainability goals. The master plan addresses:

- 3.9 million gsf of development

- Modernization of energy systems to meet sustainability goals, including decarbonization by 2035

- Renovations and new construction to fulfill space and research needs

“Maryland has also embraced design-build for many of their buildings, setting the GMP (guaranteed maximum price) at 100% documents to enable design of more complex buildings with a wide variety of program components,” says Spangler. “It has proven to be successful, and I believe other institutions will begin adapting this approach across a wider array of building types to minimize their cost risk.”

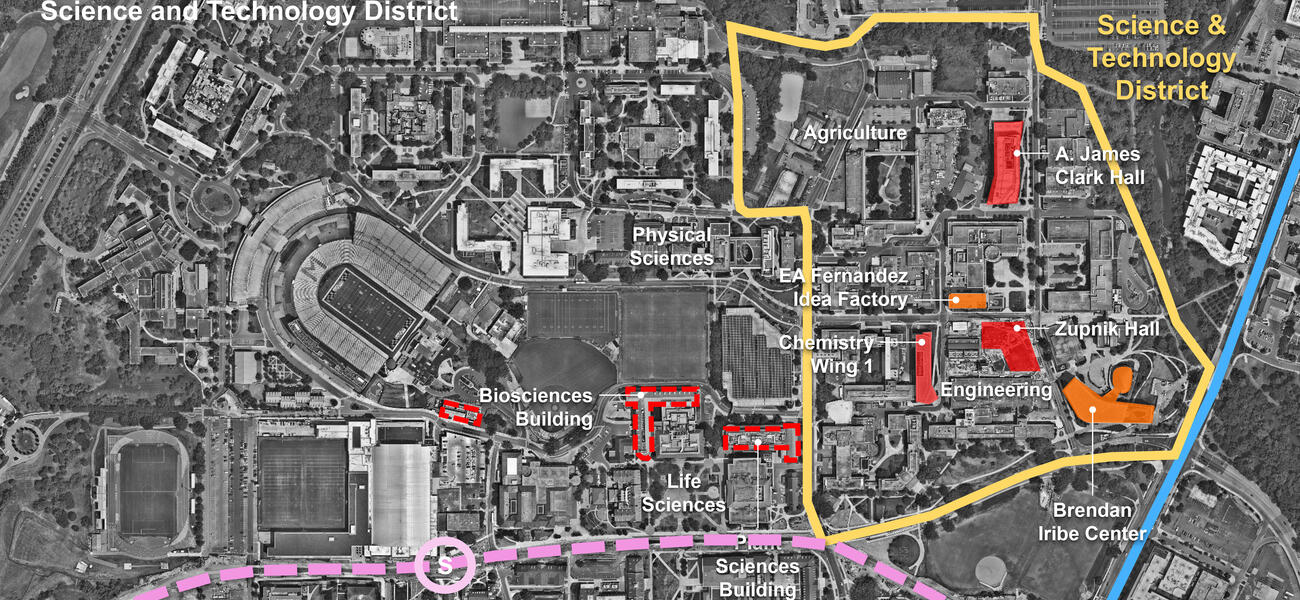

The science and engineering district includes these five new buildings:

A. James Clark Hall

Architects/Engineers: Ballinger

Opened: 2017

Size: 185,000 sf

Project cost: $168 million

A. James Clark Hall serves the Fischell Department of Bioengineering and the Robert E. Fischell Institute for Biomedical Devices. It includes three floors of research labs and offices, an MRI facility, general university classrooms, and a vivarium situated one floor below the mechanical penthouse since the building is in a floodplain, disallowing a basement area. The research environment is about 100 feet wide, with cores pushed off to the far end, allowing flexibility for different types of research.

Front and center on the building’s bottom floor is a glass-walled makerspace called the Leidos Innovation Lab, with 6,800-sf of space featuring overhead utilities, digital displays, and movable workbenches. A connected flexible area with study tables serves as a workspace for students.

“There is a visual connection with the social environment,” says Spangler. “We don’t have a big atrium in this building, so this is a working commons.”

Because the facility has a mix of environments, designers needed to consider how to approach heating and cooling systems efficiently. The team borrowed an idea from a Mercedes Benz factory in Germany when thinking how to efficiently air condition the building, and constructed a system that was the first of its kind for the university.

“Perforated round duct diffusers dump large amounts of air at a low velocity down to the floor, where it pools along the floor and then chimneys up around the people and equipment,” says Jonathan Friedan, PE, LEED AP, senior principal at Ballinger. “The idea is to condition the low places where people are, and let the air stratify on top.”

Other sustainability features include a high albedo roof to reflect the sun’s radiation, dual energy recovery wheels, neutral air ventilation with chilled beam cooling, sun shading on glass walls, high-efficiency mag bearing chillers, and 100% stormwater management and bioretention.

Brendan Iribe Center for Computer Science and Engineering

Architects: HDR

Opened: 2019

Size: six stories; 215,600 sf

Project cost: $152 million

The Brendan Iribe Center for Computer Science and Engineering was built to resemble a terrapin, UMD’s mascot, with an oval shape and two auditoriums stacked on top. The building houses the Department of Computer Science and Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS) and serves its 680 students and staff.

Also located in a 100-year flood plain, the building is raised up a level on its east end with an exterior terrace overlooking the campus gate. It contains traditional classrooms and auditoriums, offices, a makerspace, open-plan work areas, virtual and augmented reality labs, and a café. An exhibition lab’s 18-foot-tall glass walls connect the building to its outdoor landscape. In addition to modern design materials, like glass and copper, the building features a nod to UMD’s Georgian architecture with brick accents. Sun shading helps minimize direct sunlight and increase energy efficiency.

E.A. Fernandez IDEA Factory

Architects: Page

Opened: 2022

Size: five stories; 60,000 sf

Project cost: $67 million

The E.A. Fernandez IDEA Factory was designed to suggest the idea of “defying gravity,” with glass-walled bottom floors and heavier-looking solid floors above. Throughout its five stories, exposed structural elements put engineering on display, and the work done here promotes technology innovation through collaboration among different academic disciplines. The building includes 60,000 sf of lab space for the university’s Quantum Technology Center. In addition, more than 20 laboratories and flexible classroom spaces serve:

- Tom & Susan Scholl Center for Student Innovation, which includes a co-working makerspace, prototyping, and administrative offices.

- xFoundry@UMD: Focuses on student innovation and entrepreneurship, and includes a state-of-the-art video and podcast studio.

- ALEx Garage: Provides prototyping space to groups of students working to commercialize products, and includes machining and welding workshops.

- Angel P. Bezos ’69 Rapid Prototyping Lab: Provides a fully equipped makerspace that contains 3D printer and laser cutters.

- Startup Shell: Includes co-working space, pitch stage, and conference rooms for a student-run business incubator that, to date, has generated more than 60 startups.

Chemistry Research Building

Architects: Ballinger

Opened: 2024

Size: 105,000 sf

Project cost: $110 million

Serves: College of Computer, Mathematical, and Natural Sciences

Serving 600 students and housing 45 faculty, the four-story Chemistry Research Building has 34 advanced research labs, two shared research facilities with cutting-edge instrumentation and 13,000 sf of collaboration space, a chemistry great hall, and meeting and huddle rooms. Some of the research conducted here focuses on viruses, such as HIV and SARS-CoV-2, and those that cause other infectious diseases; quantum chemistry; and new instruments to advance biological research.

The site previously housed a brick wing of a larger chemistry complex. While working on the new high-performance lab building, the Ballinger team was also designing Zupnik Hall.

“Facilitating connections was such an important part of this project, both internally within the complex, but also facilitating connections with adjacent STEM buildings, acknowledging that this is a major pedestrian passage on campus,” says Jason Ciotti-Niebish, AIA, LEED GA, associate principal at Ballinger. “It allowed us to think about placemaking and the interconnection between science and engineering buildings through the establishment of shared outdoor space.”

An area that used to be a service drive is now a pedestrian-friendly passage that will eventually extend further east through the science and engineering district.

Fume hood density is an important consideration in a chemistry building, in particular, because of the high demands it puts on mechanical systems and the potentially significant impact to annual energy use/carbon emissions. In this building, an “airshare” system allows air that gets supplied to the chilled beams in offices to be drawn into labs by the fume hoods. This airshare and the use of high-performance fume hoods markedly reduces the overall requirements for supply and exhaust air.

“That also allowed us to limit the floor-to-floor heights a little more than would have been otherwise necessary,” says Friedan.

The decoupled dedicated outdoor air system uses dual energy recovery with runaround glycol and refrigerant wrap coils.

Sustainability features include:

- Low albedo roof

- High-efficiency dual energy recovery

- Chilled beam cooling for labs and offices

- Airshare

- Stormwater management

- Orientation-specific exterior shading and enhanced glazing

- Low-temp hot water radiation

The building receives low temperature hot water heating from the zero-carbon heat recovery plant in Zupnik Hall.

Stanley R. Zupnik Hall

Architects: Ballinger

Opening: 2026

Size: 163,000 sf

Project cost: $214.5 million (as of 2023)

Centrally located in the STEM district is the in-progress, six-story Stanley R. Zupnik Hall, an interdisciplinary engineering building surrounded by green space. When completed, it will become home to the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) and house 20 conference, meeting, and huddle rooms; and 31 laboratories, including a Connected Autonomous Vehicle lab and an Intelligent Infrastructure lab. Its Quantum Technology Center lab will be one of the few in this country.

“Zupnik Hall extends this idea of facilitating connections through campus,” says Ciotti-Niebish. “It also acknowledges the future urbanity of the district as it grows.”

The building is organized around a large central atrium that extends six stories with a dynamic mass timber stair, a symbol of the university’s commitment to environmental stewardship—which was front of mind in the design process.

“Our mantra is that first you have to bring the energy use of the building down as low as you can get it,” says Friedan. “You have to supply it with carbon-free thermal utilities, and then the essentially electric building is served with either purchased or generated renewable electricity. That is how you get to net zero.”

Dual energy wheels provide neutral air; chilled beams, fan coils, and room conditioning units provide local heating and cooling; and triple glazing and exterior shading reduced the mechanical systems’ size and cost. Airshare was accomplished through the atrium space: Air travels through positively pressurized offices and then gets drawn into negatively pressurized laboratories.

An innovative solution provides electrified heat by taking advantage of a local regional chiller plant located next to the building to recover waste heat.

“Heat flowing out of the chiller on cold winter days is heat that’s being rejected into the atmosphere and is the low-hanging fruit of decarbonization,” said Friedan. “If you see that, you know there is a relatively inexpensive way to efficiently generate heat electrically—take it through heat pumps and heat recovery chillers and create 140-degree F hot water. For every watt we put in, we get four watts of heat, so it’s incredibly efficient all-electric heat.”

Condenser water is diverted from the central plant to a heat recovery system that produces hot water. In addition to supplying building heat throughout the winter, this also cuts the cost to run cooling towers in the chiller plant. The heat recovery plant was the university’s first major infrastructure investment toward its carbon neutrality goal.

By Amy Souza